A job search does not usually warrant public comment. But the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s search for a permanent curator in charge of the Greek and Roman Department is a rare opportunity for this institution to reverse decades of bad policy—and bad press. With bold new leadership, the department can prove that it has learned from past mistakes and offer the public a more honest and dynamic story of classical art.

Ceramic household items and limestone funerary reliefs better illuminate how ordinary Greeks and Romans lived.

Change must begin with new attitudes of openness and transparency. Access to the department’s curatorial files on objects in the collection—which can include photographs from dealers, receipts, notes left by visiting scholars and reports from conservators—has often been denied to outside researchers. This secrecy has fuelled suspicions about the Met’s collecting practices, and in my view, flies in the face of its educational mission.

It is also time to rethink the assumption that classical collections must continue to grow. In recent years, international cultural property laws, new professional standards and shifting public opinion have made the legal and ethical acquisition of Greek and Roman art nearly impossible. And that is a good thing. Rather than spending millions on the splashiest big-ticket item on the market, the Met would better serve the public by dusting off some of the thousands of relatively humble objects in its basements, where around 80% of the collection is kept. Silver drinking cups and precious marble coffins may tell us what life was like for the ancient 1%, but ceramic household items and limestone funerary reliefs better illuminate how ordinary Greeks and Romans lived.

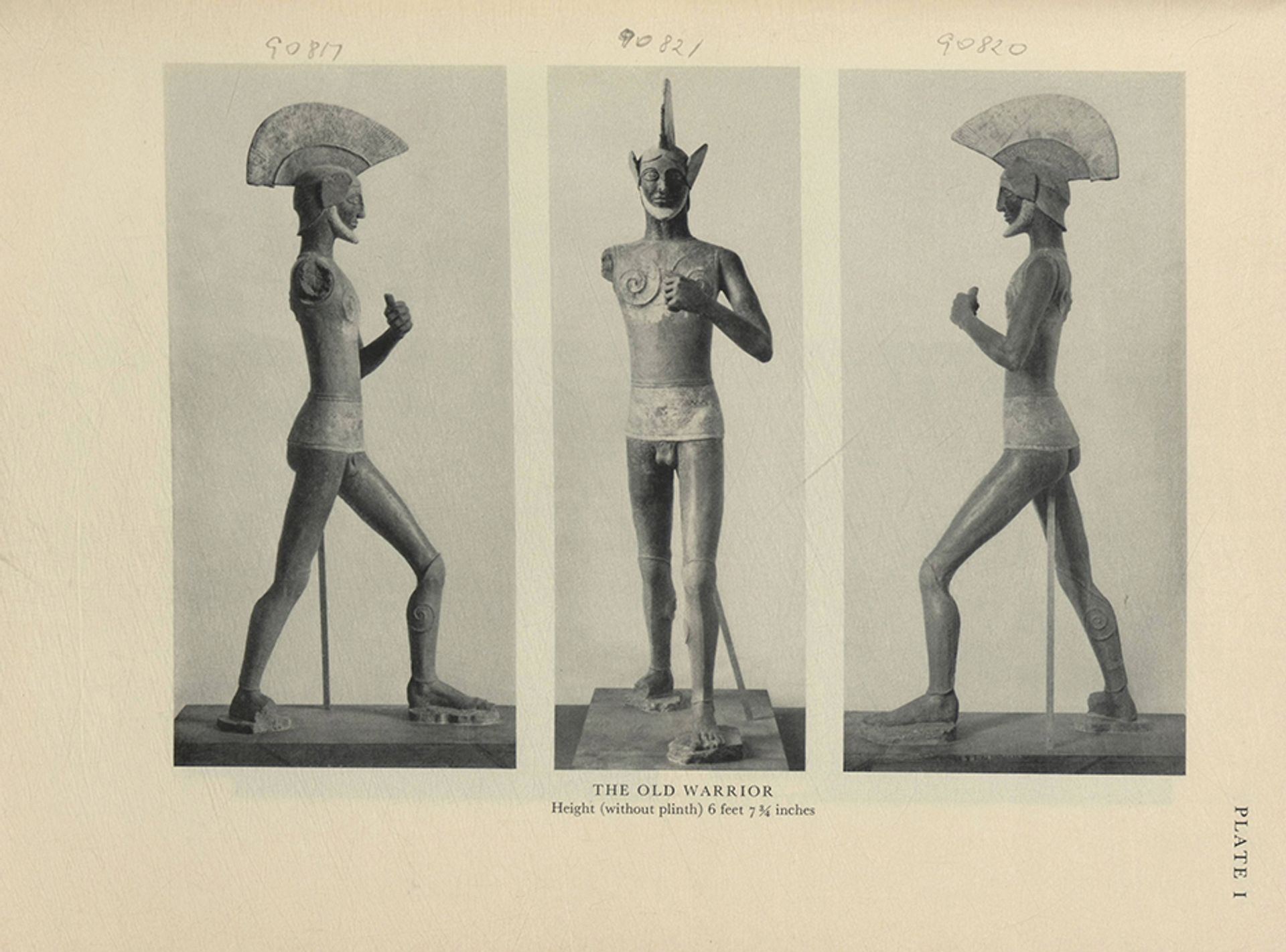

Image from Etruscan terracotta warriors in the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Gisela M.A. Richter © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Museum storerooms are also full of fascinating mistakes. These include the Met’s once muchadmired life-sized “Etruscan” terracotta warrior statues, condemned to oblivion after scientific tests in the 1960s proved they were modern forgeries. Imagine what a creative curator could do with these colourful figures.

Fresh perspectives on how classical art is presented would be equally welcome. In many respects, the Met’s galleries seem designed to affirm outdated notions of the classical world as the wellspring of Western ideals of Truth and Beauty. Other museums often display photographs of archaeologists and conservators at work to explain how ancient objects end up in museum cases. Brightly painted plaster casts are installed alongside marble sculptures to show that ancient statuary was not pure white—a myth that has given comfort to white supremacists for centuries. By contrast, the Met’s minimalist labels offer basic descriptions, biographical facts about the subject or clichés about lost Greek originals. There is rarely any discussion of how the objects were found, how they came to the museum or how opinions about them have changed over time—let alone any whiff of controversy or debate.

This is a loss, as these are often the most revealing stories these objects can tell. A bronze griffin head displayed at the museum just beyond the ticket counter was found in a riverbed at Olympia in Greece in 1914, only to disappear from the archaeological museum there years later. It resurfaced on the art market in 1948, when it was bought by a Met trustee who eventually donated it to the museum. In the same gallery is an unusual marble statuette of a seated harp player, said by several researchers outside the museum to be a forgery. The museum’s labels make no mention of these stories, or offer only partial truths; the griffin head, for example, is described simply as being “from Olympia”. Indeed, the gap between the information offered in the labels and the often provocative history of the antiquities is so great that a group called Saving Antiquities for Everyone offers its own tours of the Greek and Roman galleries, drawing attention to the details the Met leaves out.

Over Thanksgiving, I spent an afternoon exploring the American wing at the Met. I was riveted by the new, bright purple Native Perspectives panels installed beside key works there. Written from a variety of sharply personal, critical, post-colonial perspectives—and sometimes very funny—these panels are a clear sign that the venerable museum is eager to embrace 21st-century approaches to its collections, and to adapt to changing audiences. Let us hope this progressive outlook shapes the search for the new Greek and Roman curator, and that the museum leaves antiquated attitudes toward its classical collections behind.

The Met's response

“The Met’s Department of Greek and Roman Art is a highlight of our museum. While the Greek and Roman department’s files are not open, staff reply to the vast majority of enquiries. In our public galleries we display a carefully chosen selection of works that represent the breadth and variety of the cultures of ancient Greece, Etruria, Cyprus and Rome. All of the objects—including those not on view—-appear on the museum’s online database. We are also a very active and generous loaning institution, and constantly rotate what is on view. The labels in this department follow those throughout the museum, as well as our peers, and developing an innovative approach to wall labels is part of the job description for the new department head. The Bronze Head of a Griffin was a gift in 1972 from Walter Baker and has never been the subject of a dispute. The Met has also deployed modern technology to investigate the marble statuette of a harpist, which has revealed decisive evidence—the remains of pigment not immediately visible to the naked eye—that the object is ancient.”