Despite the nosebleed territory his paintings occupy in the market, Gerhard Richter is not the likeliest of subjects for a commercial feature film. Outwardly, his life story lacks the high-stakes drama of depravity, flamboyance or madness that usually sells moviegoers on a bio-pic. (I mean, Richter was in art school until he was 30.)

Never Look Away, the latest film from the German director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, doesn’t need sensational manifestations of creative genius to carry its water. It has some of the darker hours of history on its side, along with the redemptive power of art—the film’s actual subject. Nevertheless, before reaching that point, von Donnersmarck makes pit stops at sex and evil, and not just for fun.

Without resorting to the histrionics or tragic flaws common to films about Basquiat, Pollock, Picasso or the perennial cinematic favorite, Vincent van Gogh, von Donnersmarck (the Oscar-winning director of the Stasi-era, The Lives of Others, who also produced and wrote screenplay for Never Look Away) has pulled off something that even so credible an art helmsman as Julian Schnabel has not achieved.

Never Look Away is the only film I’ve ever seen that accurately portrays the creative process, from blank canvas through all of the false starts, frustrations and missteps that lead to the revelations of character and idea that make art worth pursuing.

Often this trajectory is mainly interesting to the artist following it. Otherwise, it’s like watching water boil. In von Donnersmarck’s hands, it becomes the spine of an historical narrative that doesn’t blink at the social, political and artistic legacy that Nazism left to the generation of post-war Germans represented by the Richter character, “Kurt Barnert” (played by an able Tom Schilling).

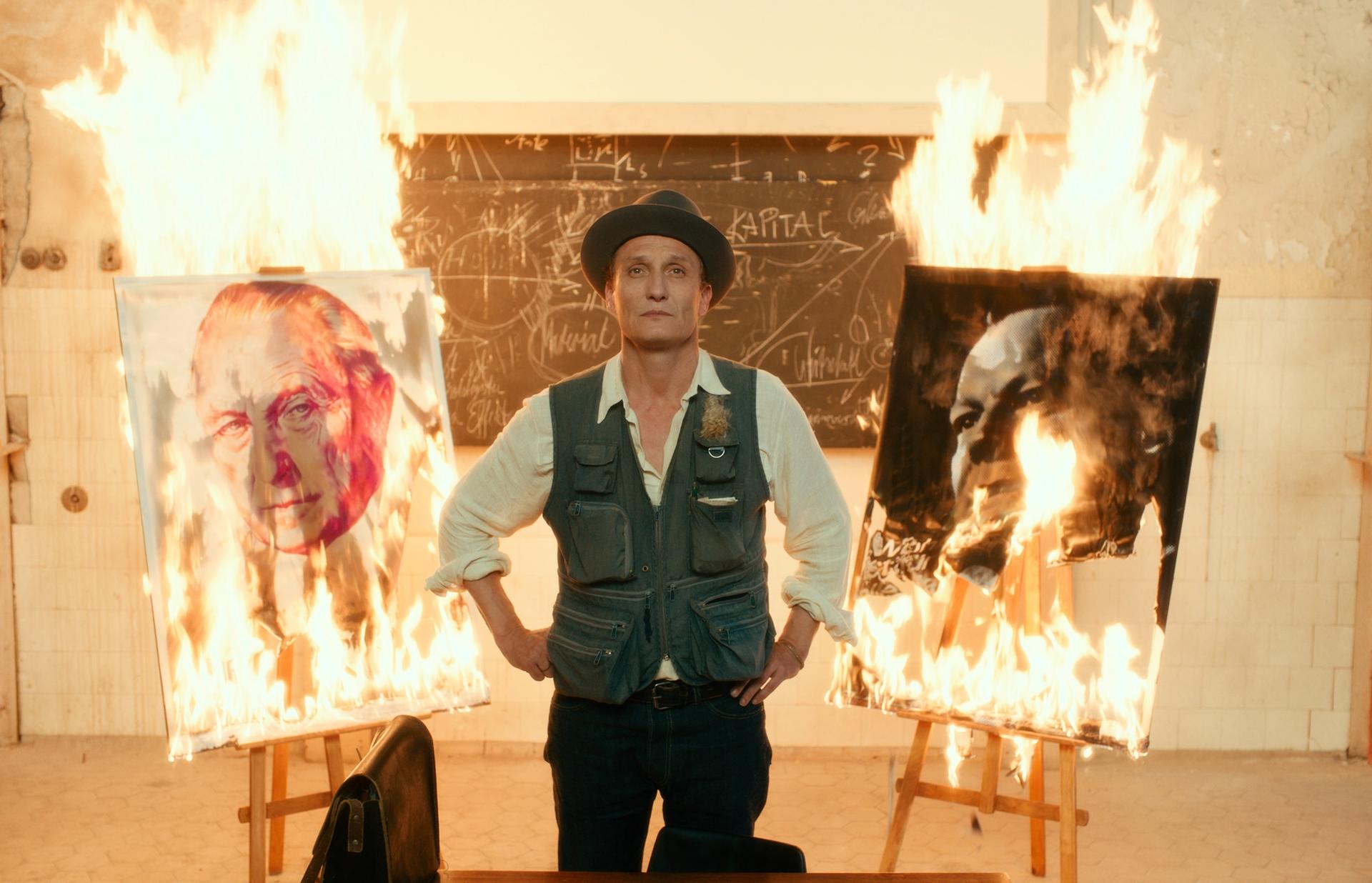

Oliver Masucci as Professor Antonius van Verten, aka Joseph Beuys Photo by Caleb Deschanel. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Loosely based on Richter’s postwar coming of age as an artist, and an adult vulnerable to love, the story begins with Barnert witnessing the firebombing of Dresden as a child, growing up in the Soviet-occupied east, and then becoming a student of Joseph Beuys and Dusseldorf Art Academy studio-mate of a character modelled on Gunther Uecker. (Art audiences will get a kick out of this, and the moment Barnert becomes the Richter we know.) Looming over the whole enterprise is Barnert’s father-in-law, an unrepentant Nazi gynecologist responsible for the sterilisation and extermination of innocents, played with chilling naturalism by Sebastian Koch (recently of Homeland).

Before a screening last week at the Museum of Modern Art, the Oscar-winning director of The Lives of Others (2006) tantalised his audience by saying that the most extreme scenes in the new film were all true. In fact, the whole thing exudes an unusual degree of authenticity. Or it did for me. Interestingly, the dealer Anton Kern, whose father is Georg Baselitz and who happened to sit next to me, pronounced it “kitschy”. (Later, he texted: “I guess it’s closer to me—east/west traumatizing.”)

Sebastian Koch as Professor Carl Seeband, an unrepentant Nazi gynecologist responsible for the sterilisation and extermination of innocents Photo by Caleb Deschanel. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

In a New Yorker profile of the director published this week, Richter expressed displeasure with both the film and the director. Nonetheless, prior to filming, he cooperated with the venture, advising the director and loaning his studio assistant to the production to remake his transformative paintings. Von Donnersmarck also consulted Robert Storr, the curator of the sweeping 2002 Richter retrospective at MoMA, and who was also at the screening. (“It’s very good but not what I expected,” Storr said.) “Until that show,” the director told him, “Richter wasn’t that well known to Americans, but it’s what sent his prices to Jeff Koons levels.”

Mainly, I think, the three-hour film owes its power to its director’s personal investment in the narrative. “We have a responsibility toward our grandparents’ generation to tell the truth,” he told me, alluding to the film’s title. “It was the artists of Richter’s generation who, in a way, restored the country.”

• Never Look Away, by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, Sony Pictures Classics, opens 25 January in the US