In the US, authors, musicians, actors, and others in the creative industries have royalties and residuals that reward their enduring stake in the redistribution of their intellectual property, when properly enforced. Yet while visual artists are entitled to royalties on commercial reproduction, there is currently little to no legal recourse for them to benefit from the resale of their work.

For a legacy interest to be codified across the US, legislation implementing a so-called droit de suite would have to pass Congress. And with a new Congress freshly seated on Thursday (3 January), an updated version of the S3488/HR6868 bill, otherwise known as the American Royalties Too Act (ART Act,) is expected to be reintroduced by incoming chair of the House Judiciary Committee, Representative Jerry Nadler (D-NY).

As the US art market continues to swell, the need for support for this bill becomes ever more necessary, especially when it comes to protecting artists with less established markets who can be more easily exploited. Case in point: demand continues to rise for works by many African American artists who have been undervalued and overlooked for decades; many are now finding success late in life yet reap no retrospective reward.

An active artist whose talent is recognized during her or his lifetime can often at least benefit from increases in fair market value, even if marginally. This is evident in the case of artists such as Kerry James Marshall, whose stratospheric rise has led to ceiling-shattering prices for African American artists. Yet when his painting Past Times sold for a record $21.1m at Sotheby’s New York in May 2018, Marshall realised nothing from its sale. Nevertheless, Marshall enjoys the benefit of high primary market sales.

The introduction of droit de suite legislation in the US would help rectify this inconvenience for well-known contemporary artists like Marshall but it would be an even bigger boon for historically disadvantaged artists who have been left out of the American canon of art for reasons of race, gender or other socio-economic limitations. This is especially true of the many artists who lack representation or a presence in the art market until the end of their careers or posthumously.

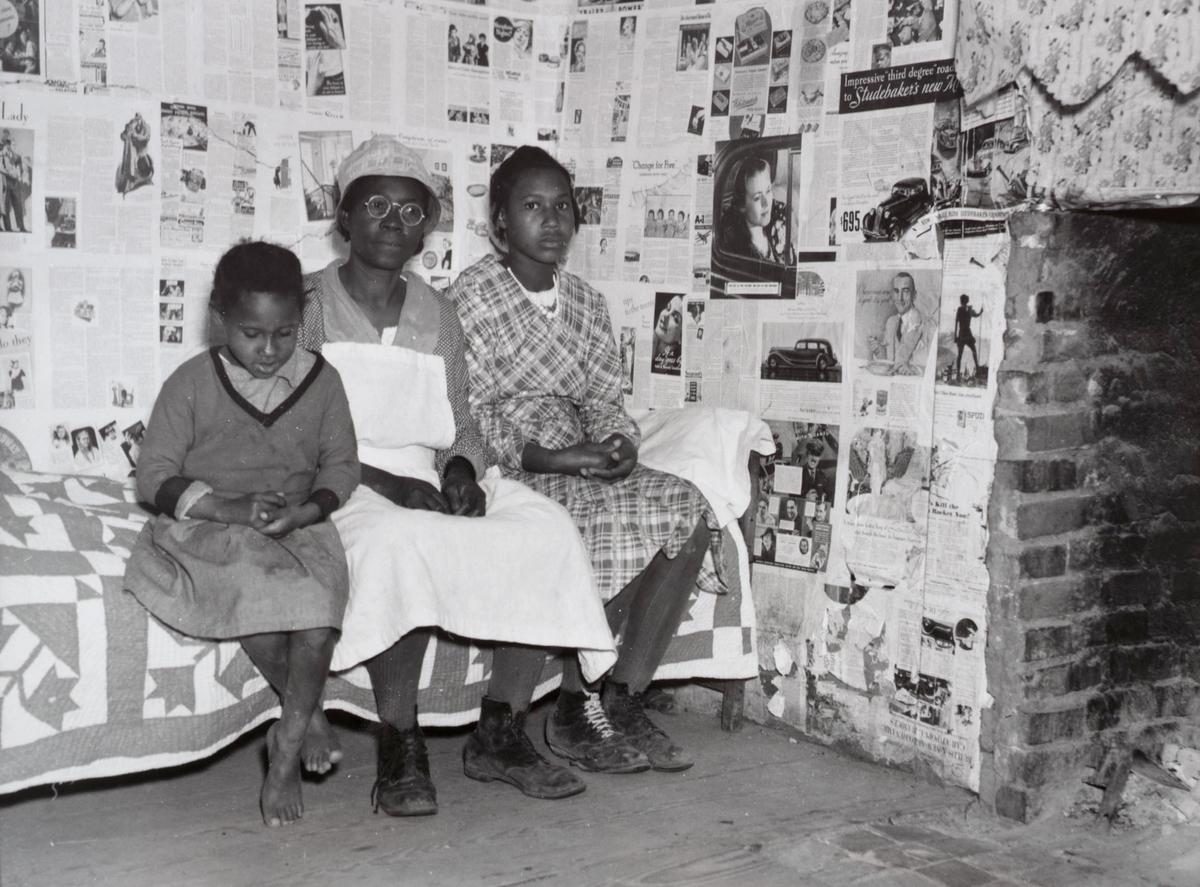

Consider the Gee’s Bend quilters of Alabama: with no access to the gallery system, many of their artworks were purchased by Atlanta collector William S. Arnett at a time when no viable market existed for their work. In 2010, Arnett donated over 1,300 artworks, including quilts and objects created by other artists, to create the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, dedicated to promoting these artists’ previously unrecognised talents.

Like many artists, the value of the quilt makers’ works has increased over time. But many of the artists have either passed away or are no longer producing works, and thus an improved market came too late to benefit them in their prime. One could cite many examples of this discrepancy throughout history, but the case of the Gee’s Bend quilters feels especially urgent given the artists’ dire economic circumstances in the rural South.

The Souls Grown Deep Foundation recognises this dilemma. As of this writing the foundation has enlisted 75 of the 160 artists or their heirs represented in its collection with the Artists Rights Society (ARS) to assure copyright protection and royalties for commercial use of their intellectual property. As a public charity, the foundation is enjoined by US law from providing benefits to individuals. It can, however, raise support and make donations to the communities that gave rise to these artists.

By permanently transferring their remarkable artworks to dozens of leading art museums through a gift-purchase model—a process started in 2016 and actively continuing—the foundation can both alter the narrative of American art history to include them and dedicate funds raised to improving the living conditions of artists and their heirs in the African American South.

Artist resale rights are already observed in over 70 other nations in accordance with the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works. In the European Union, such royalties are payable for up to 70 years after the artist’s death. France introduced the royalty in 1920; a recent French Supreme Court decision has shifted the burden for paying the royalty to the buyer.

In the US, however, only 31 states currently recognise the right for visual artists to receive royalties from their first sale. The only legislation on the books offering droit de suit protection law is California’s Resale Royalties Act (CRRA) from 1977. Perennially ineffectual, the CRRA is not only limited in scope—royalties must be paid to any descendant within 20 years of the artist’s death—it was effectively struck down in July 2018 by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which noted that federal law would need to change for such a royalty scheme to be feasible.

The ART Act could provide a small measure of equity to artists by allowing them a 5% royalty of the price paid for their work within 90 days when it is resold at auction. But the terms are still limited—all art sold for less than $5,000 is exempted, and the 5% royalty is capped at $35,000 regardless of how much the work sells for. Still, in light of the current lack of droit de suite in the US, this change would be welcome, though the bill has struggled to gain support. A previous version was introduced in 2015 and its less radical iteration introduced in 2018 did not gain much steam before the November mid-term elections, though retiring Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) showed the bill to have bipartisan support and a reasonable chance of finding Senate co-sponsors in 2019.

More can—and should—be done. An artist resale royalty is fair in principle for all visual artists. It would also address lingering inequities born of racism and allow the families of artists excluded from the art market to be appropriately recompensed.

• Maxwell L. Anderson is the president of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and former president of the Association of Art Museum Directors