I recall, as a child, browsing through a beautifully illustrated tome called the Encyclopedia of Things That Never Were. It was full of tales of creatures, places and things that were either firmly mythological or—and this I found most intriguing—in the realm of mythical history: question marks, hybridisations, exaggerations, misremembrances.

Much recorded history prior to the 18th century was based on personal recollection. Oral tradition supplied imprecise information, and archival documents supplied more, along with letters and fragments of text that were essentially personal recollections. Try to remember the dimensions of the Mona Lisa having seen it only once, or the number of floors in the Empire State Building, and it will be clear how memories can fade, distort or evaporate altogether. Then imagine hearing a description of the Empire State Building, a place you have never seen yourself. Imagine that only your grandfather’s neighbour had seen it in person, or so she claimed, and told him about it, and then he passed the story on to you.

This sort of contorted storytelling can make facts expand or contract or disappear altogether. Take the sea monster called the kraken, said to live off the coasts of Norway and Greenland. Its description recalls a giant squid, but it was part of the mythology of the sea long before mariners understood that the giant squid actually exists. Very occasional sightings of the huge creature were compared to the miniature versions that were common on the plates of coastal diners for millennia, and a legend developed of ships being broken apart by snaking tentacles.

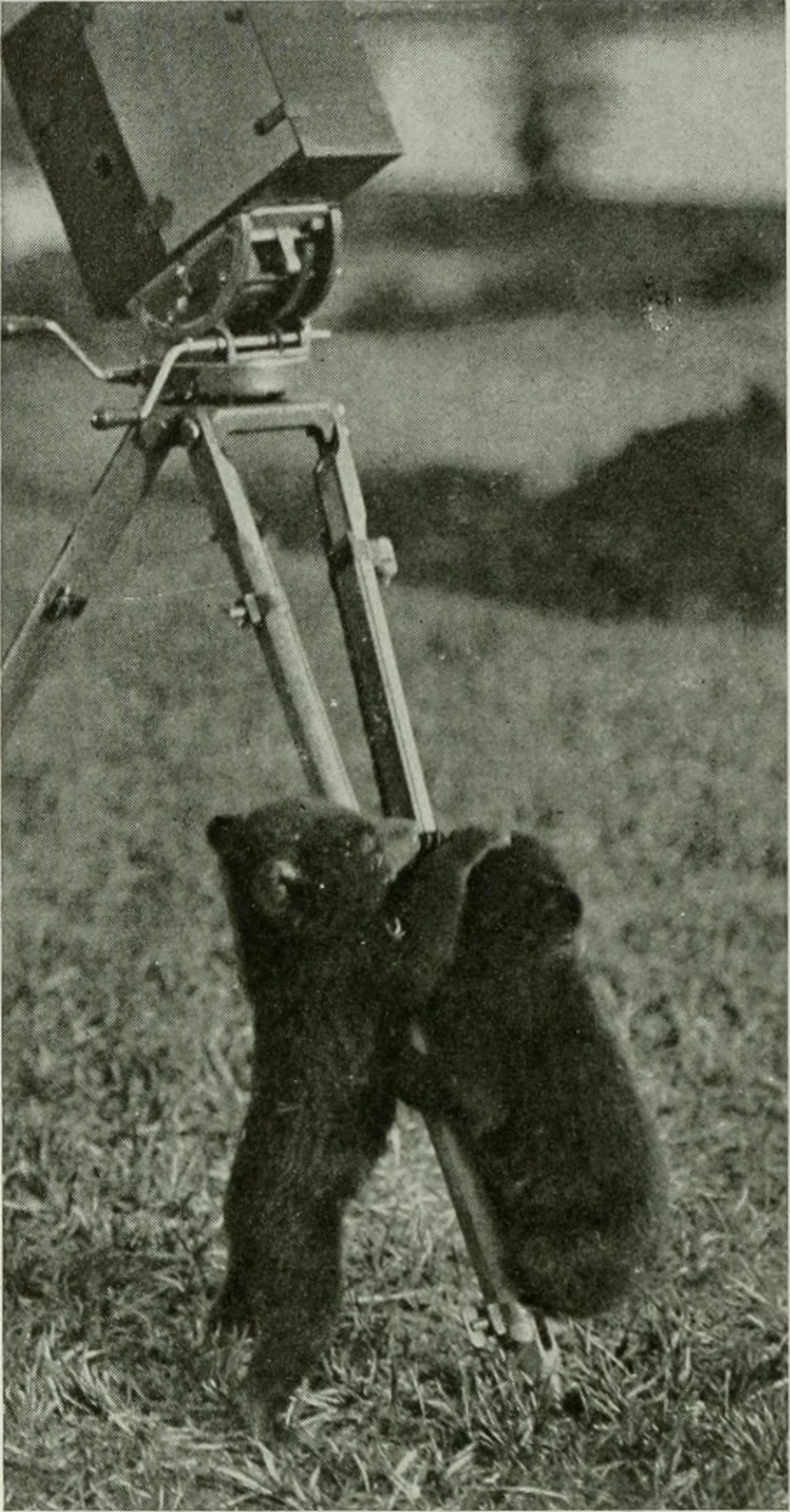

The legendary Yeti, or Abominable Snowman, is probably in reality the Tibetan blue bear, spotted by nervous mountaineers when it reared onto its hind legs. Travellers unfamiliar with the fauna of the Himalayas might have seen, through whipping winds and snow, what appeared to be a biped rearing up in the distance, perhaps growling, and from the logical explanation of a bear was born the Yeti legend. The tale expands with the telling: a 2m giant squid becomes an 18m squid, and a growl in the snow-veiled mountains morphs into a story of having been chased by a Yeti. And so encounters with real natural phenomena are expanded into monsters.

Not your average baby bear? The legendary Yeti, or Abominable Snowman, is probably in reality the Tibetan blue bear, spotted by nervous mountaineers when it reared onto its hind legs The American Museum journal

In the course of researching my book The Museum of Lost Art, I came across stories of epic searches for certifiably lost art and treasure that the searchers hoped to find, as well as objects and places that they simply hoped existed at all. Elements of the stories behind some of these famous lost objects that might never actually have existed, usually linked to origin myths and religion, have in some cases revealed the truth behind the legend: witness the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and the labyrinth at Knossos. In other cases, a trail of concrete clues, witness reports and compelling archival material suggest that tangible objects of the past, still unseen, might have actually been as the stories describe them and have possibly survived the centuries. Here are the stories of some of the famous lost cities, which straddle the gap between fact and legend.

Cities can be lost to natural disaster (Pompeii), fire (Rome), iconoclasm (Nimrud and Palmyra) or war (Carthage, Dresden), possibly rebuilt or definitively gone. In some cases, they never entirely disappeared, and in others—in areas as distant as Mexico and Egypt—they were lost even to local memory. Within a heavily forested area in the northern Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, the Slovenian archaeologist Ivan Šprajc has discovered over 80 lost Mayan cities since the 1990s. Using low-altitude aerial photography, combing the images for geometric shapes peeking through the foliage that may suggest that a man-made structure, he then sets out with his team, by jeep and on foot, to see what he can find. In a similar but higher-tech approach, the Egyptologist Sarah Parcak uses satellite photography and software to search for geometries in the Egyptian desert that suggest buried buildings and ruins. Using remote sensing, she has found several pyramids and thousands of tombs and settlement sites; her images of the city of Tanis, in the Nile Delta, have revealed large areas of the city that were unknown, despite excavation having taken place there since the 19th century.

Were cities such as El Dorado and Atlantis purely imaginary, or were they part real, part legend, evolving into something different in the process of the telling? Like the tale of the fish that got away, getting bigger and bigger each time the story is told, the legend of El Dorado, the city made of gold, sounds like an expansion of the tales told by the Spanish conquistadors of ancient cities merely rich in gold and silver, not made of it. And so it was. The story began as that of El Hombre Dorado (the Golden Man), the descriptive used by Spanish observers who described the initiation ceremonies of a chieftain carried out by the Muisca people (around 600-1600) in what is now Colombia. The rites involved the new chieftain covering himself in gold dust:

“At this time, they stripped the heir to his skin, and anointed him with a sticky earth on which they placed gold dust so that he was completely covered with this metal. They placed him on the raft ... and at his feet they placed a great heap of gold and emeralds for him to offer to his god.”

A hammered gold Shaman Pendant, 600-1500, from the Muisca people Gift of Alfred C. Glassell, Jr, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

This story and name were conflated with a 16th-century search for a city of gold called Manõa, which was said to be on the shores of the legendary Lake Parime. On his deathbed, a captain called Juan Martinez, part of the expedition led by Diego de Ordaz around 1520, described having come upon Manõa while lost, and spending seven months there. His account prompted Sir Walter Raleigh to become one of many adventurers to search for this mythical city. The last explorations were still taking place in the 19th century. There was gold in great quantities in Central and South America, quantities that seemed unbelievable in Europe, and these stories, told in letters or passed orally from man to man until they returned to Spain, helped to encourage the funding of further expeditions. Tales of cities of gold also raised the status of the speaker in the eyes of his stay-at-home countrymen, and it is not difficult to see how they might have been embellished and augmented until explorers imagined an entire city paved with gold bricks.

Another famous lost city, Atlantis, began its existence as an allegory in Plato’s dialogues Timaeus and the unfinished Critias (around 360BC) about the hubris of nation states, but that has not prevented people from searching for an actual place. The fuller description is in the Timaeus, which tells the story of the island nation that lost its godlike element over many generations and eventually fought a war with Athens, whose people refused to accept being enslaved by the Atlanteans. Athens won, and after a day and night of earthquakes and floods, the island of Atlantis sank into the sea, never to be seen again.

Given the allegorical nature of so much of Plato’s writing, there is little reason to think that Atlantis refers to a real place. Nevertheless, its story has captured the imagination of many writers, including no less than Thomas More and Francis Bacon in the 16th and 17th centuries, while a 19th-century scholar, Ignatius L. Donnelly, helped to popularise the myth in his Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882), which misconstrued Plato’s writing as a literal historical account. The public had already been encouraged to believe that Atlantis was a real lost city when it featured in Jules Verne’s hugely popular 1870 novel, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

Plato’s Atlantis may not have existed, but there have been cities swallowed by the sea or buried by earthquake, volcanic eruption or rising waters. In 2015, the Greek Ministry of Culture announced the discovery of an Early Bronze Age (third millennium BC) city off the coast of Greece in Kiladha Bay, south of Athens, covering 12 acres. It includes what seem to be fortifications with curved towers, a feature not seen in other sites of this period. Could it be that Plato’s allegory was inspired by a city like this, once present and then lost long before his time?

The search will continue for lost cities, because the real findings of archaeologists like Ivan Šprajc and Sarah Parcak reveal enough discoveries that hope remains. Myths can lead us to real findings.