The recent detention of the photographer Lu Guang in north-west China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region has sparked a global outpouring of protest. Lu Guang, who is known for his work documenting the ecological and human devastation of development in remote regions in China, is the first cultural figure from the Han Chinese majority population to disappear into the prisons of Xinjiang. But most of the region’s Uyghur writers, artists and scholars have already been imprisoned. “So many have been taken away,” says Tahir Hamut, a Uyghur poet and film-maker who escaped to the US. “Most of the more famous [Uyghur] cultural figures have all been arrested. Their families won’t say for certain, because their families are afraid.”

The missing Uyghur cultural figures include the pop star Ablajan Awut Ayup; the poet, writer and screenwriter Perhat Tursun; the dutar player Abdurehim Heyit; the footballer Erfan Hezim; the academic translators Muhammad Salih Hajim (who died in custody in early 2018) and Abdulqadir Jalaleddin; the Uyghur folklore expert Rahile Dawut; the Xinjiang University president, Tashpolat Teyip; and the former president of Xinjiang Medical University Hospital, Halmurat Ghopur.

The Chinese government claims the crackdown is on religious radicalisation, but an unprecedented level of digital surveillance is being used to punish any form of religious or cultural expression, such as owning a Koran or speaking Uyghur. The government has called Islam an “infection” to be eradicated.

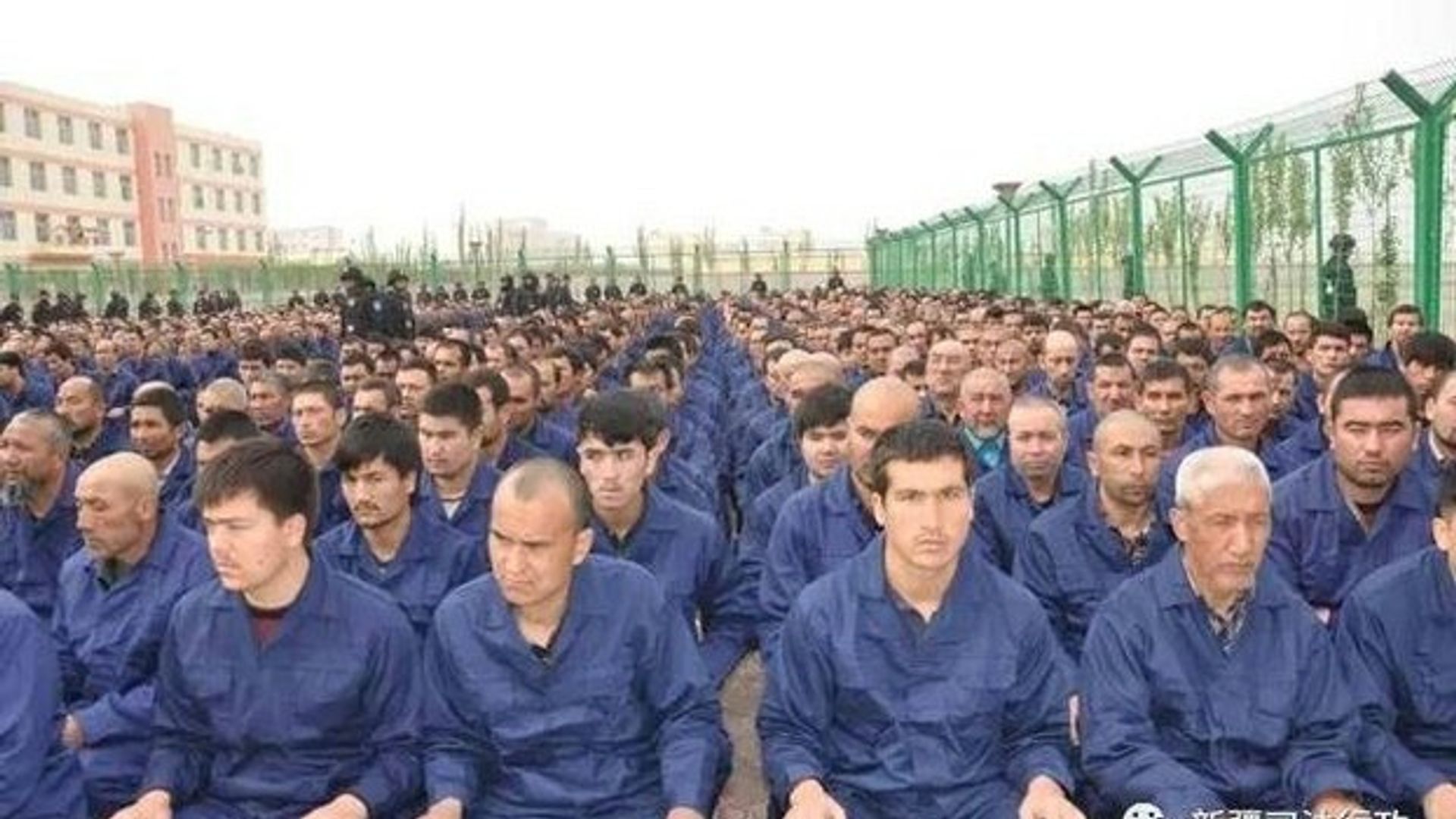

One million Uyghurs are believed to be in Xinjiang's "re-education" camps © Free Vector Maps.com

Since April 2017, an estimated one million of Xinjiang’s 11 million Uyghur population, and its smaller concentration of ethnic Kazakhs, have disappeared into what the government calls “re-education” camps, without recourse or documentation, where they are reportedly tortured into denouncing Islam and their Uyghur identity, and accepting Communist Party rule and Han Chinese dominance. The crackdown has intensified since July.

Lu was first detained on 3 November, with no news of his whereabouts given for six weeks. He had travelled on 23 October to the Xinjiang capital, Urumqi, to present a week-long workshop for photographers. On 12 December, Lu’s wife, Xu Xiaoli, wrote on Twitter that police had confirmed that the photographer was being detained in a jail in the city of Kashgar and that her lawyers have not been allowed to see Lu or obtain any formal documents. No information has been provided about Lu’s companion, who was detained at the same time, she said.

In general, visual artists and photographers in Xinjiang have fared better than the region’s writers, film-makers and musicians. One of the primary objectives of the re-education campaign is to diminish the value and use of the Uyghur language. “Many Uyghur public figures who have disappeared into the prison system were taken because of texts they wrote with the approval of state censors in the past. These texts have now been criminalised,” says Darren Byler, a scholar of Uyghur culture and a lecturer at the University of Washington in Seattle, who estimates that “the number of writers, editors, poets, musicians, film-makers and academics that have been detained [is likely to be] in the hundreds”.

A photo posted to the WeChat account of the Xinjiang Judicial Administration shows Uyghur detainees at a re-education camp in April 2017. via HRW

“From 2014 to 2016, literary and artistic censorship became intense, and everything in the Uyghur language [was routinely] checked—all songs and all papers,” Hamut says. “In 2007 and 2008, we were able to organise a few films and festivals on Muslim culture. The 1980s and 1990s were good, but since the 2000s it has got tighter and tighter; even cheesy pop culture must be pro-government. It has been a mess, especially since 2009. A lot of things went suddenly from legal to illegal. There has not been a single Uyghur-language book published since 2017, and a lot that was printed before that has not been distributed. Many things that were legal before have been taken away.”

“Many Uyghurs refer to what is happening today as worse than the Cultural Revolution,” Byler says. Chairman Mao presided over a decade of chaos during which he aimed to eradicate traditional culture, particularly religious belief, through mass re-education. But Uyghurs say the present crackdown “is worse because of the way the state has used systems of surveillance to monitor their daily behaviour and control their speech”.

In the past, he says, it was possible to find private spaces away from the gaze of the state. “They also refer to the way in which many children have been taken away from their parents as an element that is worse than the Mao era.”