Picasso: Blue and Rose at the Musée d’Orsay gathers a smashing, mesmerising group of paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures, almost all by Pablo Picasso, from around 1900, when he was still a teenager, to 1906. After that he started working on Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), which made him an international phenomenon.

I have some advice. Go through it twice, and do not read the labels the first time round. I think the objects are best experienced aesthetically and intuitively. They are so beautiful, so bewitching, that the heavy-on-art-history interpretation becomes not just static but competitive and annoying. The show promises a continuum in Picasso’s work, a gentle slide, rather than rigidly compartmentalised episodes. It delivers but sometimes what it substitutes is not convincing. It is not the end of the world. It is difficult to say something about Picasso that is both new and rings true.

Diminishing a show’s interpretation is a strange thing to suggest, I know. I am a card-carrying art historian and, as a curator, wrote thousands of labels. I think the problem is not the show but Picasso and the nature of his art history historiography. Early in his career his work was sliced and diced into periods—categorised, it sometimes seems, into mere minutes.

Picasso’s own basic problem, in as much as it is a problem rather than a gift, is that he was omnivorous, voracious and insatiable.

The exhibition works to dismantles this, but it exchanges one art history practice for another. It constructs a dense web of inspirations, among them Velázquez, El Greco, Spanish Gothic sculpture, David and his circle, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, the Impressionists, Van Gogh, Puvis de Chavannes, Cézanne and lots of others, each weaving in and out. Sometimes it feels like a flavour-of the-month.

Art historians live to do this. Using art, they create trails and progressions. At the very end of the show, there is a display case installed with art history books from the 1910s and 1920s already showing the manias to classify and to establish artistic lineage that first targeted Picasso. And Picasso targeted them. He used scholars as a selling tool. His “periods” were like new car models or higher hemlines. He loved the links they made to every great artist under the sun. It flattered his ego.

Picasso’s own basic problem, in as much as it is a problem rather than a gift, is that he was omnivorous, voracious and insatiable. He looked at everything, found value anywhere and converted what he absorbed into something uniquely his. Like the most gifted young people, Picasso was not linear. He was insanely hard working and produced thousands of objects. It is not surprising that so many of his early subjects are adolescents or young lovers or himself. That he was fascinated with sex is no surprise, either, since even when he hit 90 he was the horniest thing alive. He is finding an identity. He is majestically narcissistic. It is impossible to make a reliable map of what he saw or thought.

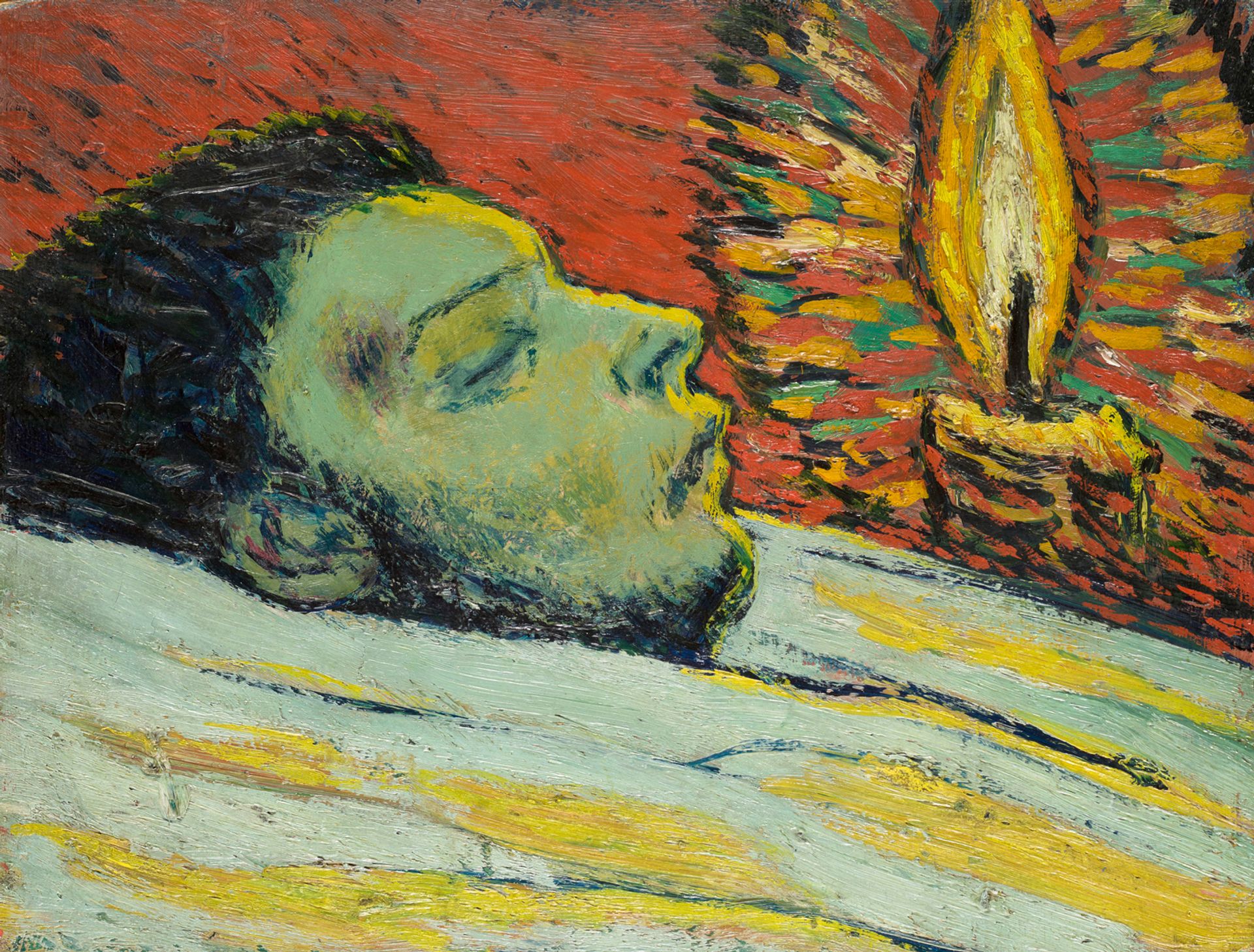

The Death of Casagemas (1901) by Pablo Picasso © Succession Picasso. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (Musée National Picasso-Paris), Mathieu Rabeau

In the first gallery, we see three Picasso self-portraits done over the time span of the show. The early one from 1900 depicts Picasso as a wild-haired, surly Romantic beast. In the next, less than a year later, he is ascetic, dressed in blue, surrounded with blue, with a sickly face tinted with blue, looking far older than he was. He does manage to give himself a natty bronze beard. The last one is mask-like, mostly contours and flesh colour. It points us to Picasso’s radical Cubist work, which was months away. The portraits give us three neat compartments. After his close friend Carles Casagemas’s suicide in 1901, Picasso does three views of the dead man in a matter of months, and these tell a more nuanced story. Each has a different look but it is subtle and overlapping.

One of the great glories of the exhibition, is the presence of all the best blue things from 1902 and 1903. Life from 1903 is there. It is enigmatic, close to a religious picture but also a nude and another Casagemas portrait.

Each painting is powerful, but I would leave aside for a moment the themes of melancholy, depression, poverty, misery, hunger and oppression, to which the curators gravitate. It is a heavy burden to put on so young an artist. Picasso might have felt sorry for the prostitutes he painted but if he had an altruistic bone in his body, ever, it was a tiny one. This is not social realism. Did he do this work to convey his own wretched poverty? I am not persuaded. Picasso rolled with the punches. He knew he was already a rising star.

A colour psychologist would say that blue, if anything, evokes intelligence, stability, creativity and an absence of emotion—a cool, detached reserve. I see these paintings first as nocturnes, a favoured subject in French art at the turn of the century. The artist in Picasso probably sought angular motifs accentuated by candlelight, a selective chiaroscuro. He found the planar, geometric features he wanted in half-starved prostitutes and women in the prisons he visited. He could not find the look among professional models, even if he could afford them. Focusing on line and pattern, he used a uniform colour to avoid distractions. A colour linked to cerebral contemplation helps even more.

Picasso's Celestina (1904) © Succession Picasso. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (Musée National Picasso-Paris), Mathieu Rabeau

Picasso’s men friends have faces. His prostitutes often do not, except the distinctive one-eyed madam in Celestina (1904). They are objects, often bony, and when he gives them faces, they are either generic or grotesque. The exhibition text describes the subject in The Blind Man’s Meal (1903) as “the suffering of this modern martyr”. Martyr to what? He might have looked closely at El Greco, but El Greco had only just been rediscovered. Picasso saw his work once, on a short trip to Toledo. El Greco did no subjects like those in Picasso’s blue paintings. Blue really was not his colour, except for his nocturnes. The show calls Picasso’s figures “mannerist” and “expressionist” but what would these have meant to Picasso? Probably nothing.

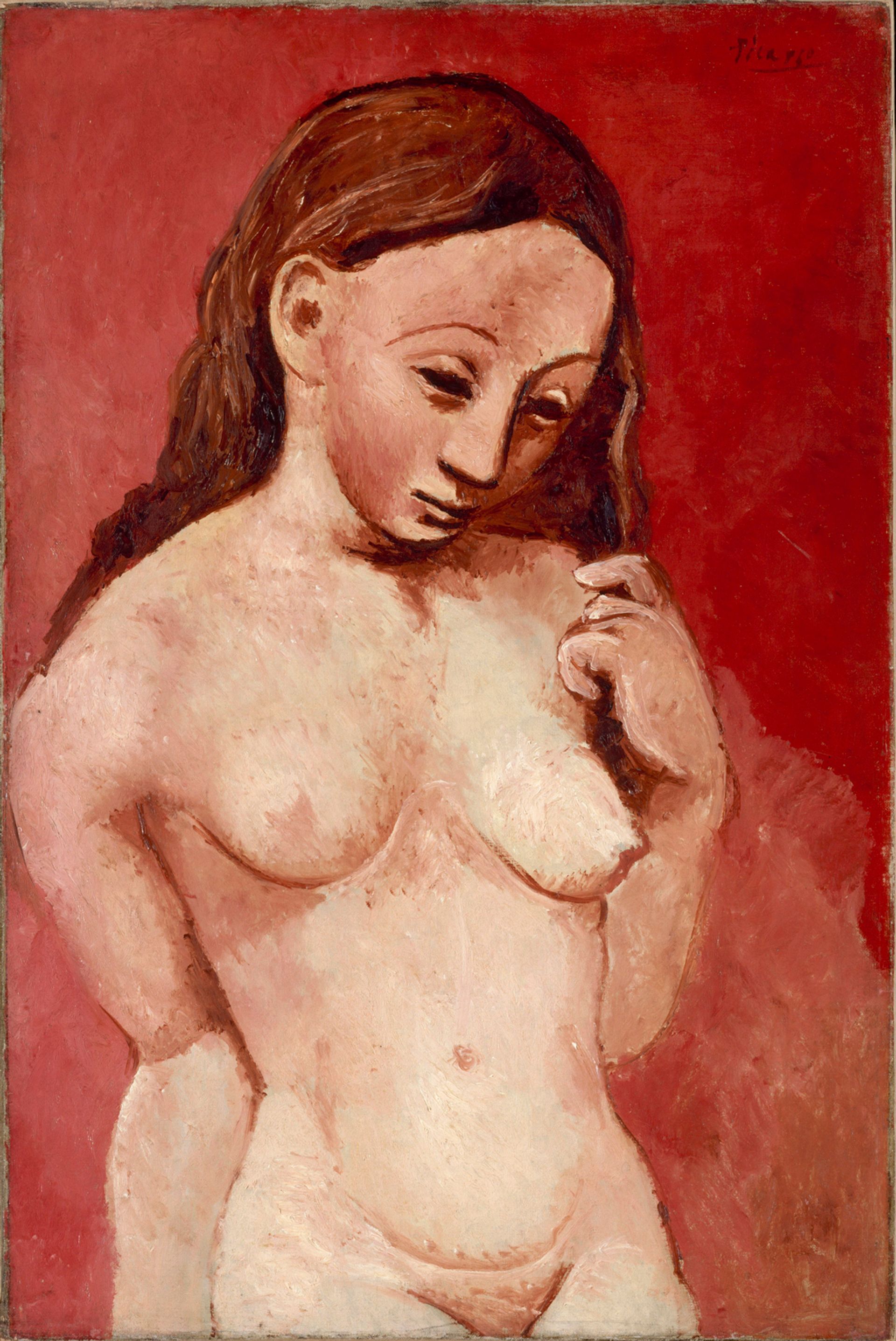

The most beguiling—and mysterious—works depict the acrobats, jesters and organists from the Medrano Circus in Paris, the cryptic profiles of young women and Boy Leading a Horse (1906), a painting I have loved for years. It is worth seeing it just for these works from 1905 and 1906. They are cryptic, even dreamlike. The figures are less flat and more sculptural, looks he achieved in part through broadening his palette to include rose and ochre but, especially for his women, he still uses plenty of blue. They have a whiff of Tonalism. The contours are wide, dark but chalky, and the transitions from colour to colour are exquisitely gradual. In Boy Leading a Horse and Acrobat on a Ball (1905), there is no narrative. After a surfeit of meaning, I welcomed their inscrutability.

Picasso's Nude with a red background (1905-06) © Succession Picasso. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (Musée National Picasso-Paris), Mathieu Rabeau

Whether deliberate or accidental, the show has a functional second half in the Cubism show simultaneously on view at the Pompidou Centre (until 25 February). In his work from 1907 to around 1915, he avoids emotion and narrative like the plague.

Does the show have a worthy purpose? Yes, emphatically. There are few museums in the world with the capacity to assemble so many great things. And experiencing them individually and in juxtaposition is priceless.

• Picasso: Blue and Rose, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, until 6 January