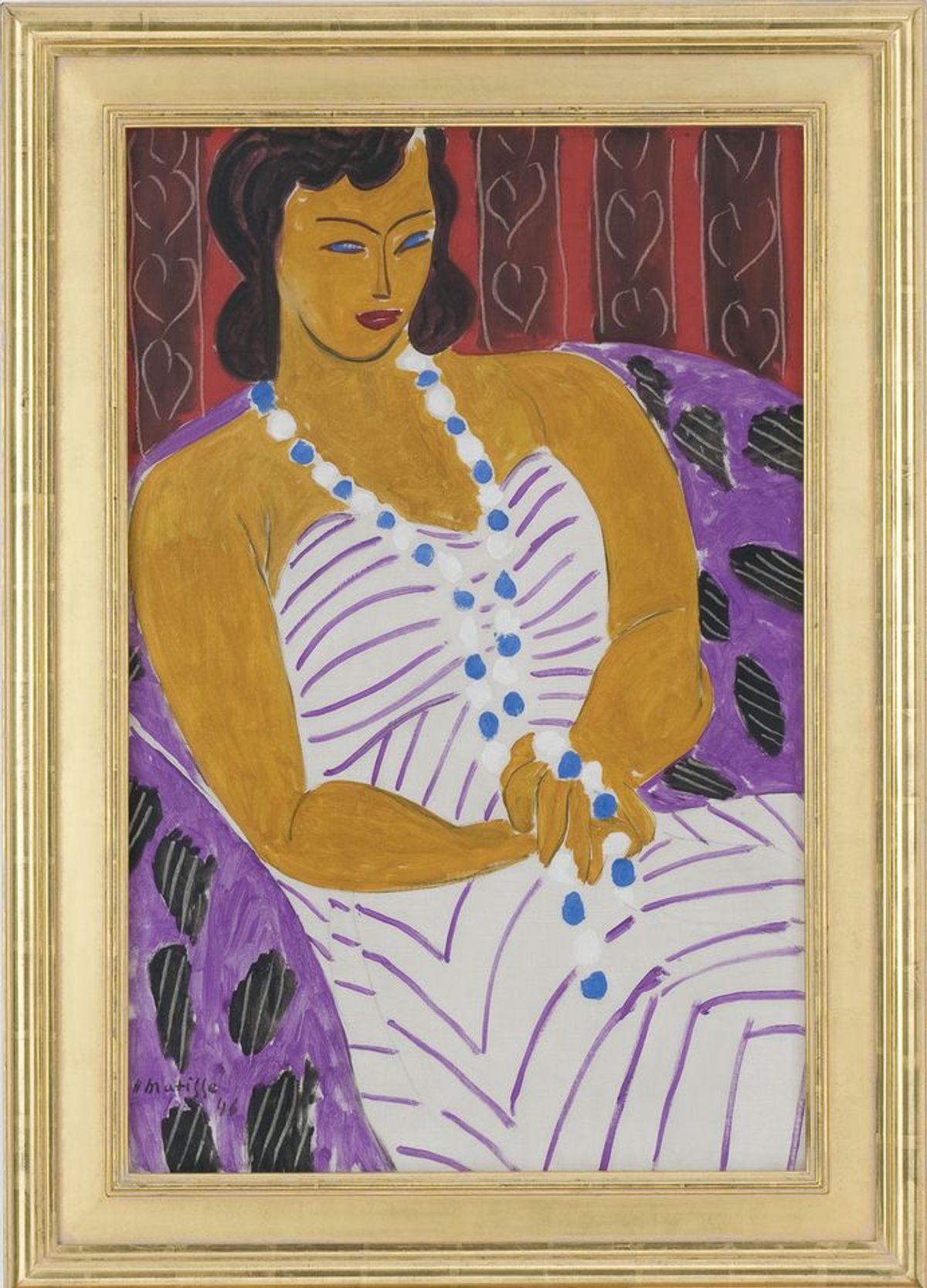

Posing Modernity: the Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (until 10 February 2019) at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery is a successful mix of academic chops—a much-needed rewrite to Modern art history—while also being fascinating, direct and simply a pleasure to see. It began with the curator and scholar Denise Murrell’s desire to know more about Laure, the largely forgotten model for the maid in Manet’s Olympia of whom “next to nothing [was] said” in a lecture, leading to Murrell’s doctoral thesis and this exhibition exploring the black model as central to Modernism. An especially interesting section features works by Matisse, who spent time in Harlem and whose “style—his mode of portraying the black female figure—evolved into something that had a lot of affinities with the Harlem Renaissance”, Murrell says, along with artists like Charles Alston. Stop to take in the small portraits by photographers like Félix Nadar of black Parisians in Manet’s milieu, which “help people understand that these images we see in paintings were not symbolic—they were representations of a lived presence”, Murrell says. The show ends with works by contemporary artists like Ellen Gallagher and Mickalene Thomas.

After a visit to Calder / Kelly (until 9 January 2019) at Lévy Gorvy, you might be surprised that there has never before been a major show that pairs the works of these two giants of American Modernism. The artists met in Paris when Alexander Calder was 52 and Ellsworth Kelly was 27, and shortly after, in 1954, struck up a friendship stateside. Calder took the young Kelly under his wing, from paying his studio rent once, to helping him score his first show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the group survey Sixteen Americans in 1959. The gallery's three-storey show allows ample room to appreciate both artists' works, around three dozen paintings and sculptures made between 1940 (Calder’s Black Beast, among his earliest large-scale sculptures) and 2014 (Kelly’s Yellow Curves, a painted aluminium sculpture resembling a reversed B). Look for the similarities between their works—even before their friendship, such as the juxtaposition of Black Beast with Kelly’s Plant II oil on wood (1949), both organic subjects abstracted in black—including play of positive and negative space and two and three dimensions, or their use of black and white, and vivid, often primary, colours.

While we have supposedly passed peak millennial pink, the broader colour is still having quite the year, from the midterm election pink wave, which brought record numbers of female politicians to Congress, to Janelle Monáe’s catchy anthem to womanhood, Pynk. See why the colour is anything but passé at the Museum at FIT in the exhibition Pink: the History of a Punk, Pretty, Powerful Colour (until 5 January 2019), which includes clothing and accessories from the 18th century to the present, as well as toys, music and video—like the music video for Pynk, next to a replica of the ruffled “vagina pants” Monáe wore in it. Elsa Schiaparelli, known for her 1930s “shocking pink”, Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons, Cristobal Balenciaga and Jeremy Scott of Moschino are among the international roster of designers featured. Take time to read the labels, as interesting as the garments themselves, to find out when the word pink entered the English language, which Thomas Gainsborough painting contributed to the coding of pink for girls, who said pink was the most rock-and-roll colour of them all and other fun facts. Beyond the surface, the show is a meditation on gender norms, sexuality and politics—like all fashion.