“You can’t really, as a photographer, tackle the subject of American western photography without coming to grips with [Ansel Adams],” says Karen Haas, the Lane curator of photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). “He is someone who is this larger-than-life, iconic figure in the field.” Haas has organised the new MFA exhibitions Ansel Adams in Our Time (until 24 February), which includes major works by Adams like The Tetons and Snake River, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (1942), as well as pieces by his 19th century ancestors like Eadweard Muybridge , Timothy O’Sullivan and Carleton Watkins and artists today who are influenced by his legacy. From Adams’s work, the show “jump[s] to very contemporary work that seems to me to be responding either to a place or a theme directly within Ansel Adams’s career”, Haas says, with more than 20 contemporary photographers and artists including Catherine Opie, Trevor Paglen and Binh Danh looking at themes such as environmental destruction and preservation and southwest Native American life. The exhibition celebrates a gift of nearly 500 photographs by Adams from the Lane Collection, announced in 2012 and now being formalised.

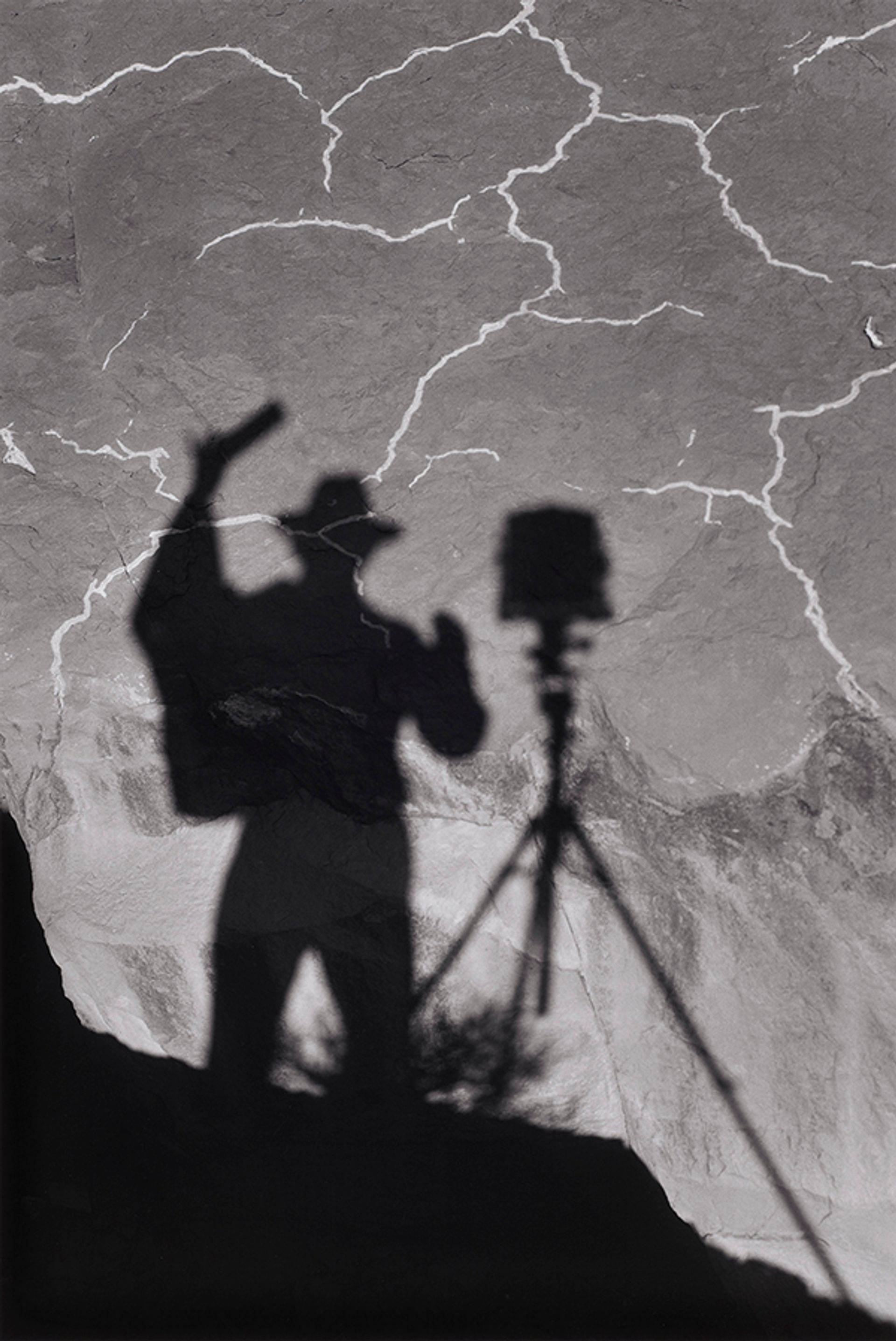

Ansel Adams, Self Portrait, Monument Valley, Utah (1958): “I’m very interested in the idea that he’s so often described as though he was not influenced by anyone else—that he’s seen as this singular figure, always treated as a separate conversation,” Haas says. “I think it really makes for such an interesting conversation if you look at him in light of the people who were his precursors 19th century who were finding and codifying these views of Yosemite.” The Lane Collection © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust; courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

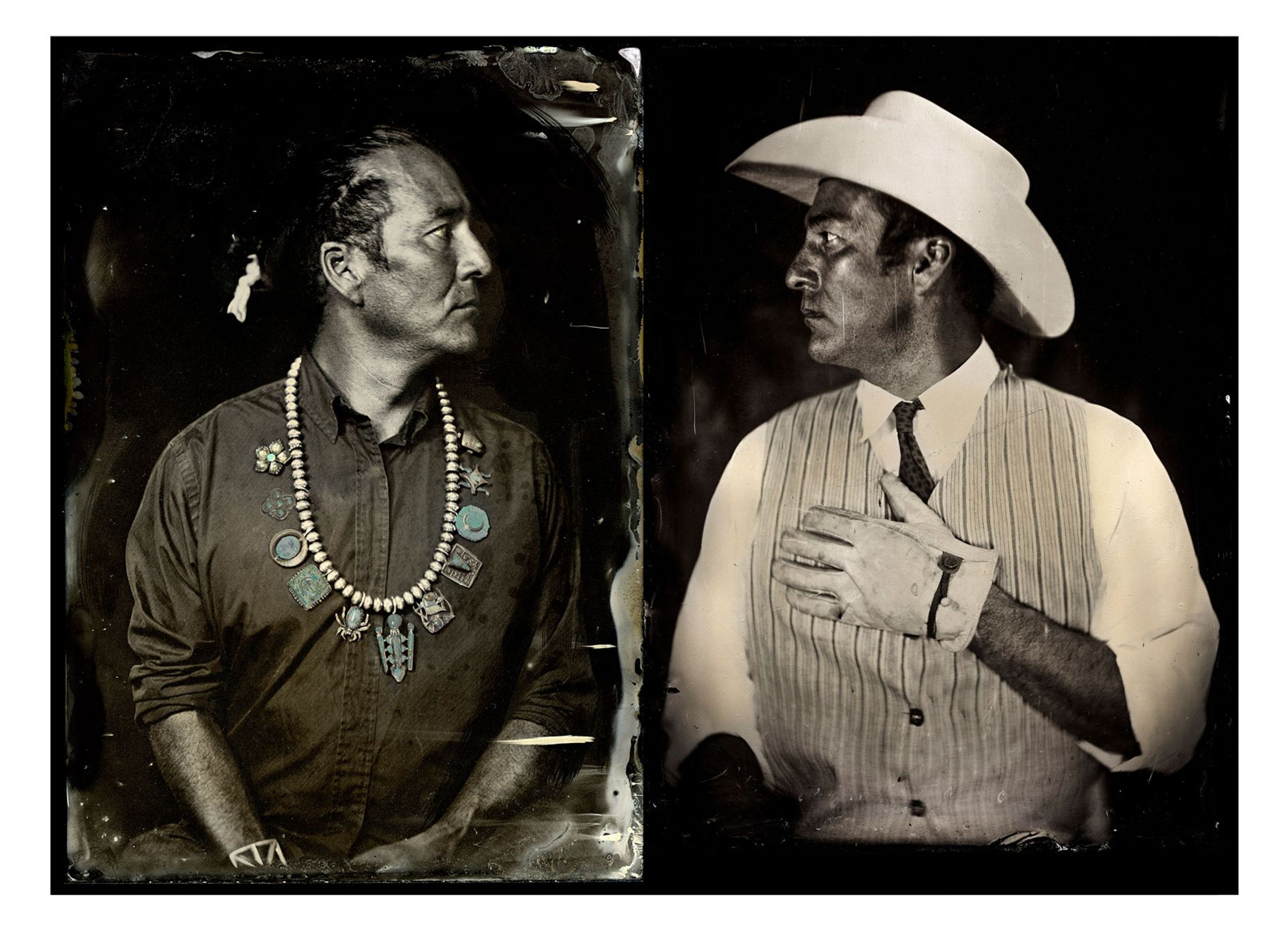

Will Wilson, How the West is One (2014): The west “has been perceived by white settlers as empty—and we all know it that it wasn’t empty at all, that it was a place that seemed just ripe for our imaginings about who we were, what it meant to be American: all these ideas, that of course left aside the stories of native peoples who were already living there or allowed for all kinds of very one-sided stories to be told,” Haas says. A gallery dedicated to Native American life in the southwest shows rare 1920s photographs by Adams of Pueblo Native American ceremonial dances and earlier images like Hedipu, Navajo Woman (about 1879) by John K. Hillers, but also work by the contemporary Diné (Navajo) photographer Will Wilson. He uses the 19th-century tintype process to make portraits that have a similar subject matter to works by these earlier white photographers, “but very much talking about personal agency” and the way that being a native photographer “changes his approach, his thinking to photographing his own people, his own community … the sitter is very much an equal partner in this conversation”, Haas says. © Will Wilson; courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Catherine Opie, Untitled #1 (Yosemite Valley) (2015): The photographer and artist Catherine Opie, whose work often focusses on her lesbian community in Los Angeles, is “maybe last person you’d imagine in the National parks,” Haas says. “Yet she, too, is finding the national parks as this very rich vein to experiment with, and what I love about her work is she’s sort of saying, ‘Wait a minute, this is not just the domain of white men—this is a place where I can see myself’ …She’s photographing the same falls and the valley [in Yosemite as Adams]... But she’s photographing them in colour.” There is also a video work by Opie in which she talks about Carleton Watkins. © Catherine Opie; courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul; courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Trevor Paglen, Untitled (Reaper Drone) (2015): “The environment is a big piece of what we’re talking about” in the show, Haas says. The Eastern side of the Sierra Nevada is “more drought ridden today, because so much of that water has been siphoned off to feed Los Angeles, Las Vegas [and] places like that.” Besides being used for this purpose, they have been used for incarceration and government activity, Haas explains. For instance, in his work, Trevor Paglen is “looking at the various ways that we have used these ‘black holes’ in the landscape—these otherwise empty raw, otherwise not very arable lands, and turned them into places where the government [and] the military are building and doing things that we’re not often aware or knowledgeable about”. Haas compares this with Adams’s photography documenting daily life in the internment camp for Japanese-Americans in the Second World War at Manzanar, first published in 1944 and a little-known part of his work (also on view in the show). Adams once said that “from a social point of view that’s the most important thing I’ve done or can do, as far as I know”. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York ; courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Abelardo Morell, Tent‑Camera Image on Ground: View of Mount Moran and the Snake River from Oxbow Bend, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (2011): “One of the things I was struck by when I was working on the National Parks section, which is one big central gallery, is all the other photographers besides Opie are foreign-born—which had never occurred to me when I was choosing them,” Haas says. Among these photographers is Abelardo Morell. “He talks about being Cuban-born, and the idea of having grown up in Cuba as a kid and watching westerns and coming to the United States as a teenager and thinking that everyone [was going to] talk and look like John Wayne,” Haas says. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Ansel Adams, Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park (around 1937): “It’s not so farfetched to say that [Adams’s] vision is something that has really formed a lot of our visual itinerary of this space,” Haas says. “We [at the museum] we always joke that when you think about Yosemite, most of us conjure up views that are black and white.” The Lane Collection; © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust; courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Ansel Adams, Self Portrait, Monument Valley, Utah (1958): “I’m very interested in the idea that he’s so often described as though he was not influenced by anyone else—that he’s seen as this singular figure, always treated as a separate conversation,” Haas says. “I think it really makes for such an interesting conversation if you look at him in light of the people who were his precursors 19th century who were finding and codifying these views of Yosemite.” The Lane Collection © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust; courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

MFA Boston brings Ansel Adams into the present day

“You can’t tackle the subject of American western photography without coming to grips with him,” says the shows curator

Ansel Adams, The Tetons and Snake River, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (1942) The Lane Collection, © the Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust; courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston