When Jordan Casteel was in residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2015, the young painter wanted to capture the energy of the street vendors she saw daily. With her camera, she mustered up the courage to approach people about making their portrait, including James, who was selling CDs in front of Silvia’s restaurant, wearing a fedora and matching suit.

“The light was hitting him so magnificently, this 70-year-old man with beautiful chocolate skin,” says Casteel, who took dozens of snapshots of him to use for her painting. “I told him my goal was to get him on the walls of the museum.” James, who had never been inside the Studio Museum, was taken aback by the size of the painting when he showed up at her studio exhibition and ran out to bring back his wife, Yvonne. “She threw her arms around me sobbing and thanked me for seeing him as she had always seen him,” says the 29-year-old artist, who has become something of a surrogate child to the couple.

Jordan Casteel, Yvonne and James (2017) © Jordan Casteel. The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection, San Francisco. Image courtesy of the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York

Since receiving her MFA from Yale in 2014, Casteel has attracted much attention in the art world for her deeply empathetic large-scale portraits of African Americans who inhabit her everyday communities—whether family and friends from her hometown of Denver, fellow students at Yale, or denizens of Harlem where she now lives. A second portrait she made of James with Yvonne is one of 29 paintings in the artist’s first major museum exhibition, Jordan Casteel: Returning the Gaze, opening at the Denver Art Museum on 2 February.

We tend not to notice people on the periphery, and those were the people she was engaging

“Jordan is having these interactions with the sitters that make a difference in both their lives,” says Rebecca Hart, the curator of Modern and contemporary art at the museum, who organised the show. She was first drawn to Casteel’s series, Visible Man—nude portraits of classmates at Yale in their domestic settings that were shown at the Lower East Side gallery Sargent's Daughters in 2014, the artist’s first exhibition, which sold out. She is now represented by the gallerist Casey Kaplan, and has her second solo show with him next November. “Her work evolved from there to visible-invisible—what we notice, or don't notice, about society,” Hart says. “We tend not to notice people on the periphery, and those were the people she was engaging.”

The granddaughter of the Civil Rights leader Whitney Moore Young Jr, and the daughter of Lauren Young Casteel, who runs The Women's Foundation of Colorado, the artist studied sociology and anthropology at Agnes Scott College in Georgia before switching to studio art her senior year. At Yale, Casteel fused her passion for painting with social justice in Visible Man, her thesis project.

Jordan Casteel, Galen 2 (2014) © Jordan Casteel. Collection of Charles L. Casteel. Image courtesy of Sargent's Daughters, New York

“I was thinking about how to bring humanity to the black male body in a time that has villainised the black male body, or sexualised it, or taken advantage of it historically,” says Casteel. She painted the skin of her naked classmates, whom she asked to look directly at her camera, colours such as bubblegum pink or green, initially as a formal challenge. But she liked the way it subverted how viewers might perceive blackness.

As they hand over control of their image, they are maintaining agency wherever they go through their gaze

Today, she continues to heighten her palette as a way of complicating the paintings, and to have her subjects meet her eyes—and thus the viewers’. “As they hand over control of their image, they are maintaining agency wherever they go through their gaze,” Casteel says. These portraits now reside in private collections, including that of the singer Alicia Keys, and the rapper and music producer Swizz Beatz, as well as institutions such as the Studio Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, where the Denver show will travel next September. Hart, interested in diversifying the Denver Art Museum’s collection, is spearheading the acquisition of two paintings from the show.

Returning home as a “Denver daughter” is an out-of-body experience, Casteel says. She remembers visiting the Denver Art Museum on school trips. “The makers of whatever was within those walls were not people I thought I could identify with,” she says. “It wasn't something that I saw as an ambition I could have for myself.”

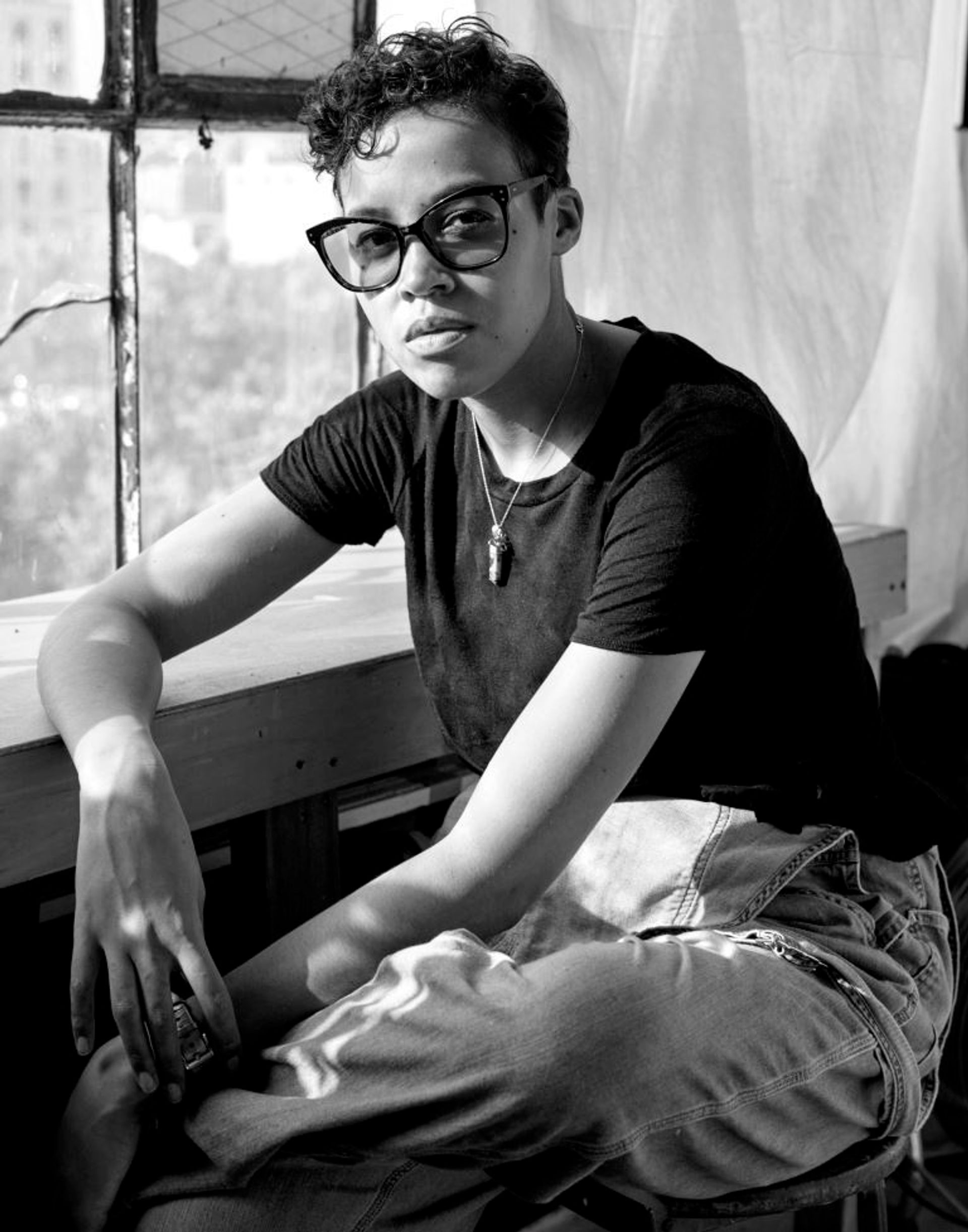

Jordan Casteel © Photo: David Schulze. Courtesy of Casey Kaplan, New York