Elizabeth Price uses digital video to weave together images, sound and text drawn from often wildly disparate sources—including historical archives, animation, pop videos and motion graphics. Her richly layered moving image installations, which often take years to make, hover between social history and fantasy and won the Bradford-born artist the Turner Prize in 2012. Price studied art at the Ruskin School and the Royal College of Art but she also had a career in the music business, as the co-founder of the Oxford-based indie pop band Talulah Gosh, in which she was one of the singers. Price’s solo show at the Walker Art Center is her first commission from a US institution and consists of two new films, KOHL and FELT TIP, both made in 2018. In distinct but also interconnected ways these take in a characteristically wide range of motifs to reflect on a broad range of issues, including the relationship between the material and the digital, sites of labour and markers of gender and social class.

The Art Newspaper: KOHL plays with the relationship between coal and ink, while FELT TIP features the electronic and digital design motifs of men’s neckties from the 1970s and 1980s. What was your initial thinking behind these two new works?

Elizabeth Price: Both pieces started from trying to think about the relationship between the cache in the computer, its hard drive and the edit process. When I make my films I have millions of files and images that I collect together and I suppose the task is finding a way in which I can attach these to each other.

Was this capacity to accumulate and meld an enormous amount of material one of the main appeals of using digital technology?

The point where I started making video was the point where on a laptop you could move between publishing, image-making and desktop sound-making software. These things are overlapping and I find the institutional difference between, say, publishing and art and music quite boring. In my work now there are bits that are writing and there’s graphics and compositional music. I’m defined as a visual artist and that’s fine, but in a way it’s to do with trying to invent and create something using whatever languages are available and meaningful to you. In these new films I’m trying to hang something off something else—a bit like making a really ugly sculpture. So they are about letting this density of material have an expression in the edit, which is a bit like the surface layer for all this stuff that’s in the dark space underneath.

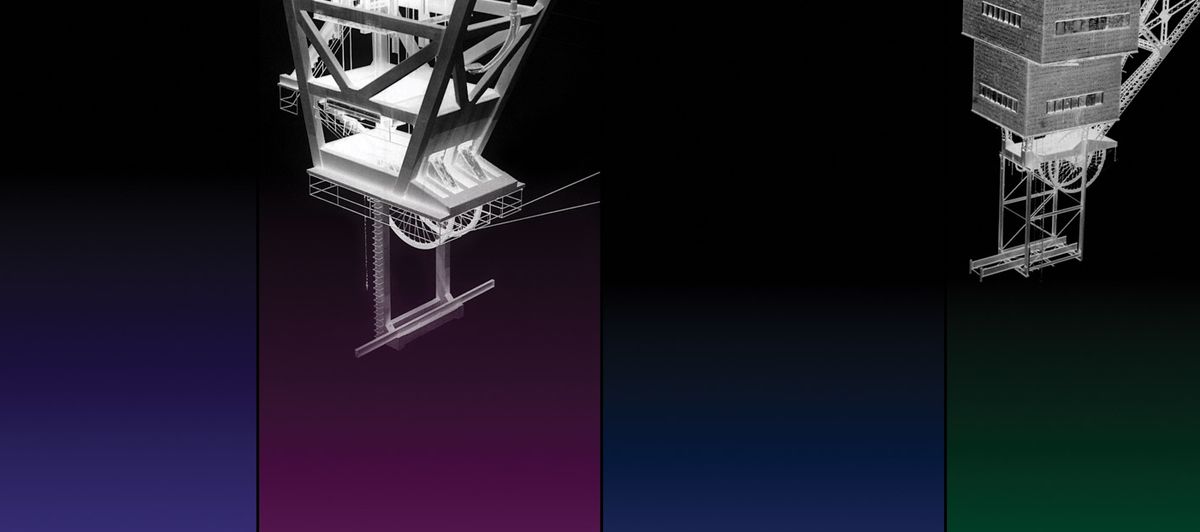

KOHL refers to a network of underground spaces that have been excavated beneath new buildings and through which a black, inky substance comes seeping up.

I was thinking about this subterranean layer and how that could be expressed through fiction, which is what I increasingly try and do in my films. I started thinking about the geological history and creation of coal, the carboniferous swamps and how it built up. Then of course there’s the significance of coal in the Industrial Revolution and in the politics of the 19th and 20th century, which is followed by the moment where coal begins to decline and the social-political problems around that. So it seemed a really interesting way in which I could take this rather private, nerdy and not very interesting idea about the computer hard drive and find something analagous to it which could have a more broadly applicable meaning.

This idea of what the narrator in KOHL describes as a “big wet grid” of “inky spit” that has flowed from the north to the south is a very visceral one.

One of the most common—and fatal—industrial diseases related to mining was black lung, which produced what was called “inky spit”. So there’s this idea of this involuntary symptomatic emission from the history of mining, from both the problems of its production, the violence of its precipitous termination and the collective failure to deal with the burden of debt that we have to the people who have taken this stuff up. And this emission is here manifesting itself in these cold and useless places that are barely inhabited.

The film is also making a political statement.

KOHL is to do with the politics of our current time. Things are now emerging that have this incredibly deep historical provenance around the end of the Industrial Revolution. The miners’ strike took place when I was about 18 and deciding my politics, and I understood it in terms of people losing the dignity of work and the dismantling of communities. Although my family is from the north, I grew up in Luton and didn’t understand that when the mines were closed these areas became not only places without an economic function but also sites of mourning. So my film features the mineshafts, the head frames, all these photographs taken by Albert Walker which are now gone, but of course all the subterranean architecture remains under the surface. And its ongoing legacy remains hugely significant for all of us as well as for the communities that were absolutely dependent on coal.

FELT TIP occupies both lower and upper screens while KOHL is projected solely onto the lower. Why this configuration?

One of the things I was thinking about in FELT TIP was the relationship between the subterranean irrational memory and the upper executive space of language—in other words, between the cache and the edit—and also the relationship between managerial, administrative and manual labour. The neckties which form such a conspicuous part of FELT TIP have a decidedly managerial feel, as does the language used by the mechanical narrative voice, although often what the voices are actually saying then subverts this executive tone.

“What has emerged over the past year of #MeToo is this sense of deep memory”

For me, the narrators in FELT TIP are the same people who speak in KOHL. I think about them as this rather bored administrative workforce; they are probably working-class women who have ended up in middle-class work and who are probably cleverer than their bosses. They are bored and they are taking the piss. I think of them as characters, although they don’t really exist socially in any fully formed way.

The ties in FELT TIP are almost characters in their own right.

Years ago I started to collect these ties from the 1970s and 1980s that had imagery which seemed to be really expressive of the emergence of electronic media: things like computer chips and computer networks. I became really interested in that moment, which of course in this country is the same moment as the decline of coal mining. And within the period of the ties, this demographic shift is also matched by a change in the technology of the office. In a sense, the positioning of this technical imagery on the ties, instead of the crests of upper-class provenance such as public schools or elite clubs, would seem to be arguing for a sense of potential. But of course this wasn’t opened up to everyone and hasn’t been sustained particularly well. In FELT TIP the administrator/narrators are observing this, and they make their own claim on the idea of the tie as a symbol of authority and on its phallic imagery. In turn, this is also related to the nib of the pen and its successor in the digital age: the fingertip on the keyboard. The narrators lay claim to these things as a form of satire and critique but they are also furious as they speak of their long, long memory of how the promise of inclusion was not extended to them. What has emerged over the past year of #MeToo is this sense of deep memory—people have not forgotten.

FELT TIP seems ominously relevant.

I started working on this film two years ago when I was thinking more in terms of social class, race and gender. Then all our worst fears were confirmed about the workplace experience for so many people, and all these memories are being connected together because they never had expression before. And while that has been in some sense an emancipating moment, there are of course very disturbing manifestations as well.

How do you feel about these two films about British situations being shown in the US?

The KOHL story especially is different in America, where coal mining is still a thing and people are living through some of those processes. So I’m excited to show the works in America but I respect that these things are very much alive.

• Elizabeth Price, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 8 December-23 February 2020

Biography

Background: Elizabeth Price was born in 1966 in Bradford, England and raised in Luton, Bedfordshire. In 1988 she took a fine art BA at The Ruskin School of Art in Oxford and an MA at the Royal College of Art in 1991. In 1986, Price co-founded Oxford-based indie pop band Talulah Gosh; she shared the band’s vocal duties. The band became defunct in 1988. Price stated: “I left because I didn’t enjoy being on stage. I was always interested in the experimental possibility of art, and pop—even when it is strange and unusual and exciting—is committed to certain forms. I love these forms and often use them in my films, but I am also interested in other things.”

Milestones: In 2005, Price was awarded a Stanley Picker Fellowship at Kingston University and in 2012 became the first artist-in-residence at the Rutherford Appleton Space Laboratory in Oxfordshire. She has continued to teach, most recently as a lecturer in fine art at the Ruskin School and as a professor of film and video at Kingston College of Art. Price won the Turner Prize in 2012 for her solo exhibition Here at the Baltic Centre of Contemporary Art in Gateshead. Other significant shows include Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna, in 2014; Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 2010; the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, in 2013; and the Art Institute of Chicago in 2017.

Representation: She is represented by Grimm Gallery in Amsterdam and New York.

Three key works

Price's The Woolworths Choir of 1979 © the artist

The Woolworths Choir of 1979 (2012)

The three-part video weaves together photographs of church architecture, internet clips of girl-band pop performances and news footage of a deadly fire in a Woolworths furniture store in Manchester in 1979. “In this film I was trying to find a point of connection between these three different bodies of material: the churches, the girl groups and then the narrative of the fire,” Price says. “The way I figured it out was with the gesture of the twisting, turning wrist; it was exciting to make that realisation and to find a way to connect such disparate things in a single work.”

Price's A public lecture and exhumation © the artist

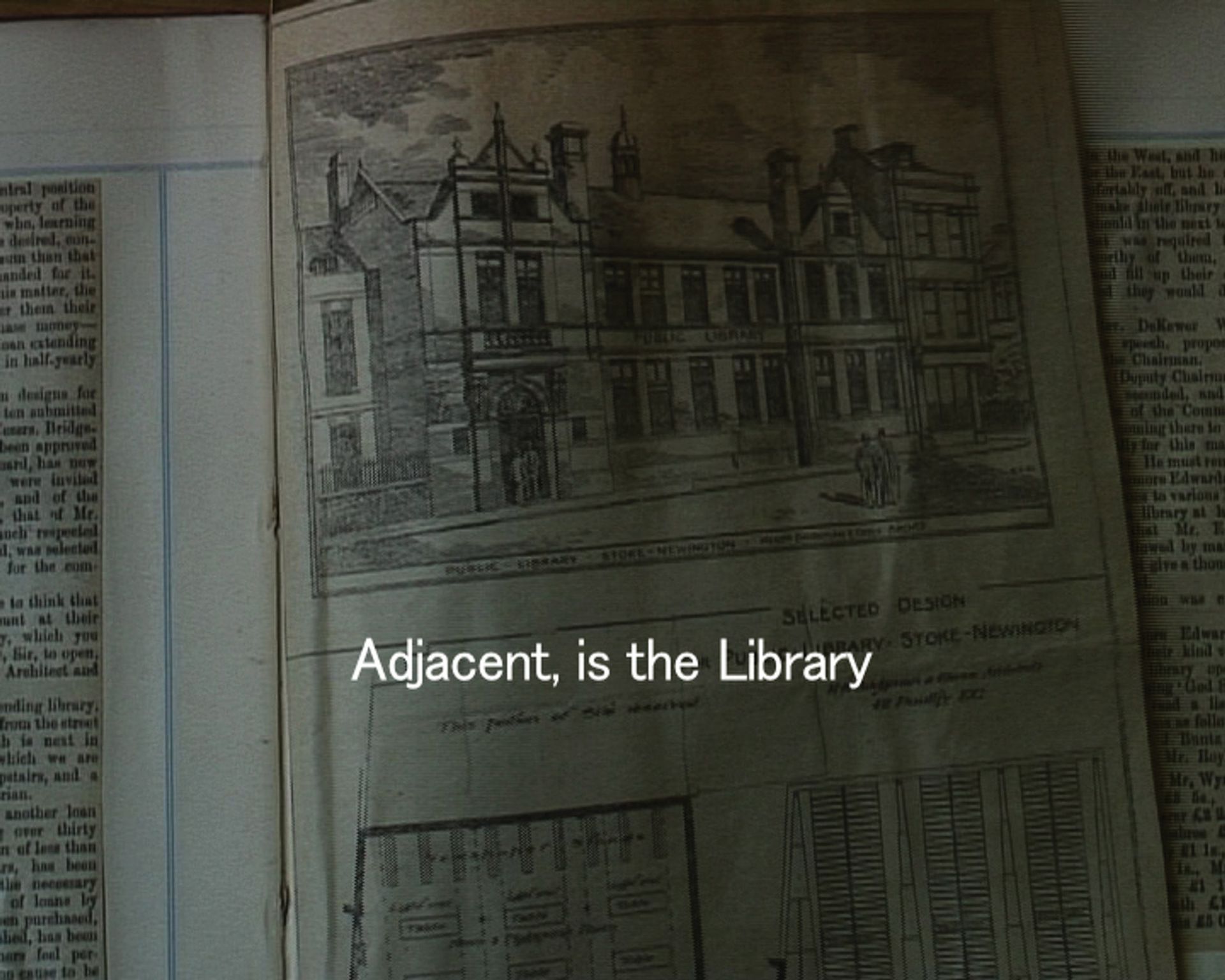

A public lecture and exhumation (2006)

Price has only shown this film once, at Studio Voltaire in 2006, and describes it as “the first narrative video I ever made”. She adds: “It’s not very good but I really loved making it.” Narrated by the former libraries committee of Stoke Newington, the work assumes the form of a tour around the London borough and features a donor who bequeathed it his collection. In Price’s words, the purpose of these narrators is “to excavate bits of this collection as being like the dismembered body of the patron”.

Price's K © the artist

K (2015)

Price considers K to be “probably the first film I wrote that was more like a short story”. On one screen a stop-frame animation of the sun—created from thousands of glass-plate slides taken between 1870 and 1948—plays continuously. On the other, a CGI animation of the production of nylon stockings, each packaged under the brand name K, is interrupted—or accompanied—by footage of dancing performers, including the 1970s country singer Crystal Gale. Binding these visual elements together is a narrative composed by Price and attributed to the Krystals, a fictional group of “professional mourners” who perform not only at funerals but also christenings, weddings and art exhibitions.