Thanks to her seminal Dinner Party installation (1974-79), Judy Chicago is literally famed for giving women a figurative seat at the male-dominated table of history. This week an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami (ICA Miami) brings together seven of the artist’s other bodies of work produced between the 1960s and 1990s to present a fuller picture of Chicago’s own contributions to the history of art, including lesser-known and rarely exhibited pieces.

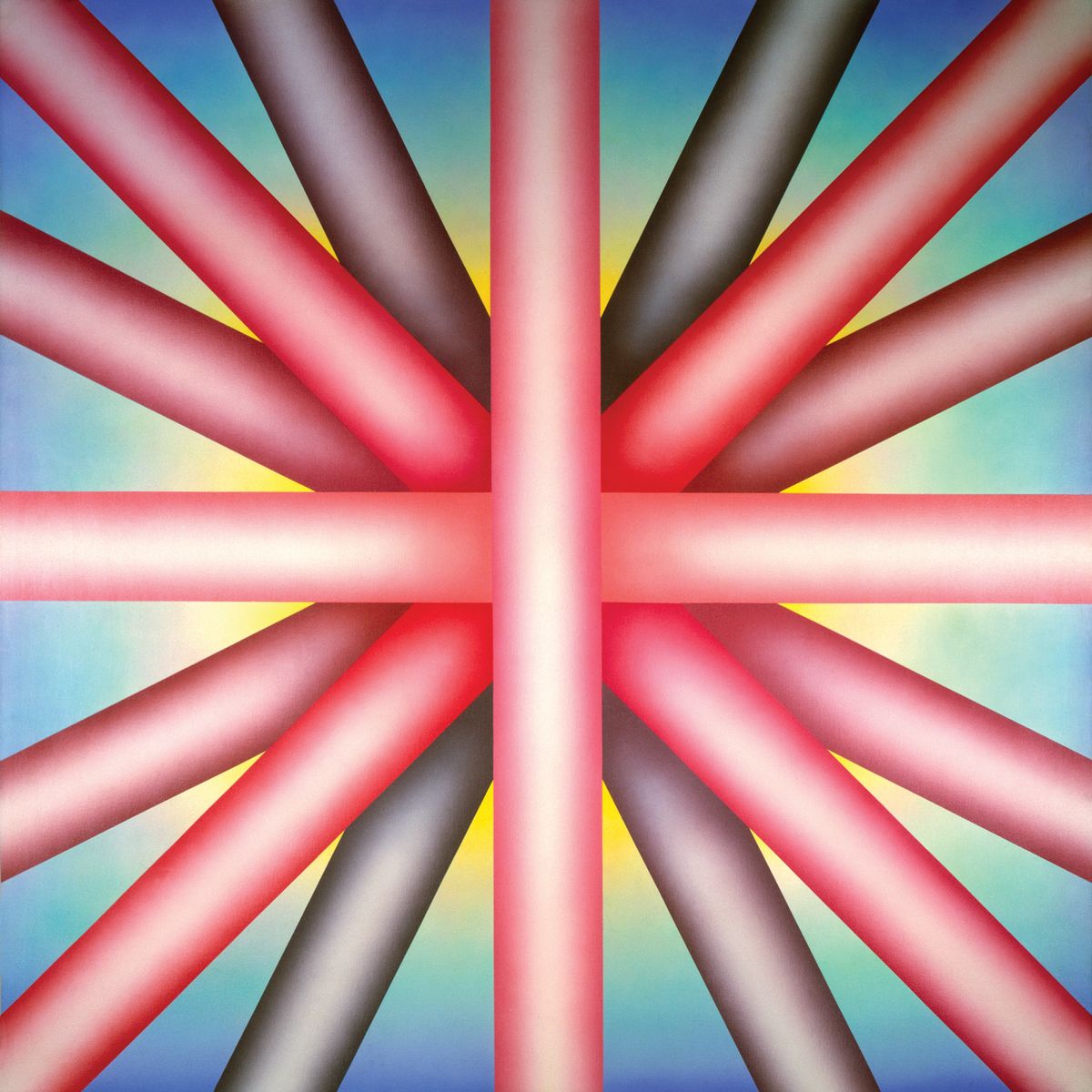

Judy Chicago: a Reckoning offers one of the broadest surveys of the artist’s diverse career to date, exploring her early Minimalist sculptures and paintings—such as her brightly hued Op-art-inspired canvas Heaven is for White Men Only (1973)—and her transition to figuration, as demonstrated in works from her 1990s PowerPlay series.

Interest in Chicago’s work has been on the rise as more institutions re-evaluate the inclusivity of their post-war and contemporary collections. Yet according to the ICA Miami’s artistic director, Alex Gartenfeld, the 79-year-old artist’s work has always been timely, having consistently dealt with themes such as the social mechanics of power, female agency and even ecological disaster.

She brings more energy to the table than any artist I have met

“Something that’s always surprising to me is how for decades her work as a whole was treated as less important in a variety of ways,” Gartenfeld says. He adds that both critics and scholars have lauded her work, while subtly suggesting it did not stack up to that of her male peers. “It was either too didactic or not formal enough,” he says.

Chicago, however, invited the comparison of her work to that of her male contemporaries—she often directly references many of them, even if obliquely. The exhibition aims to foreground her staunchly feminist voice, which continues to reshape the historical canon’s understanding of Modernism.

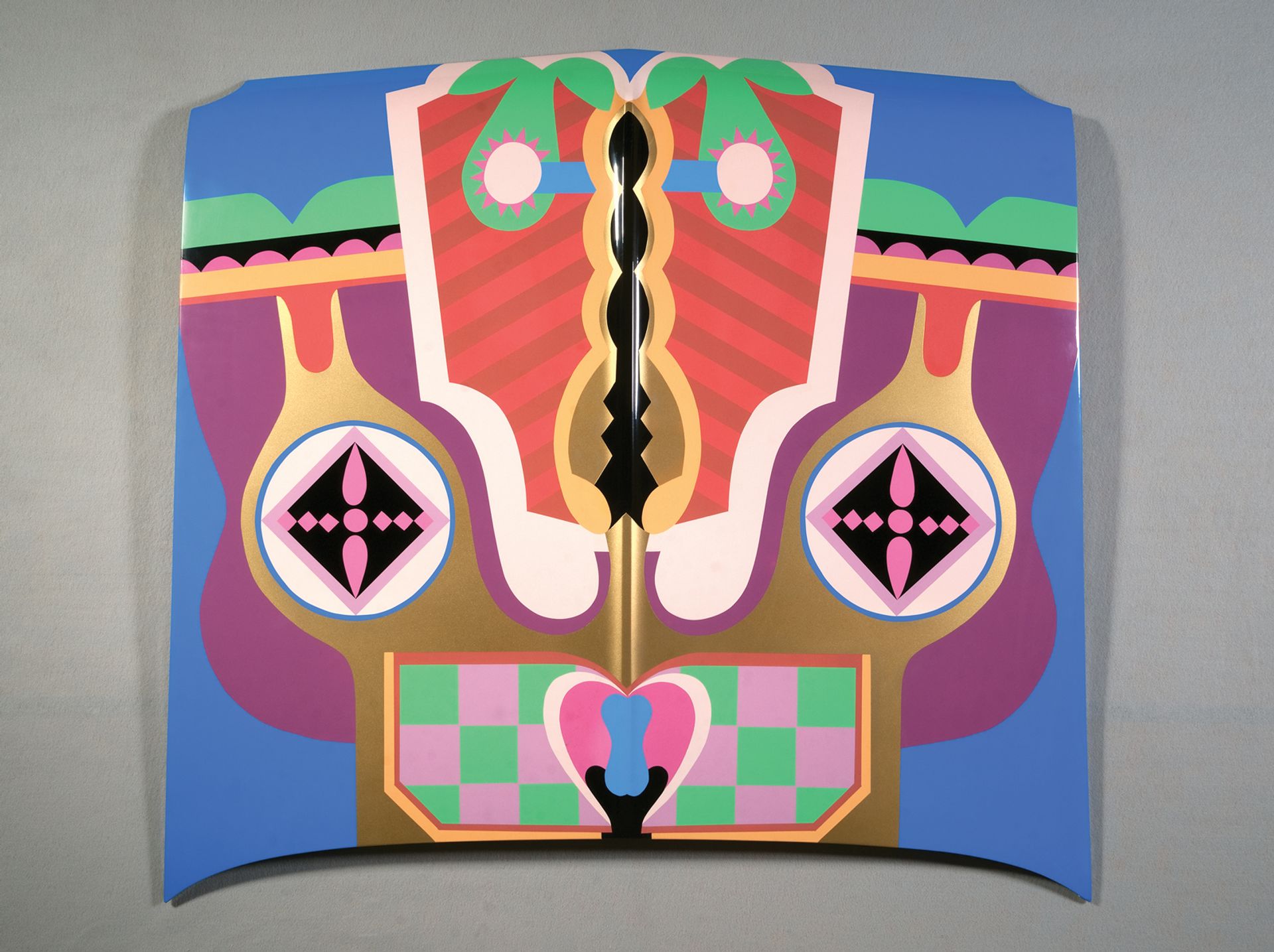

The show will include test plates for the Dinner Party, shown publicly for the first time, as well as Chicago’s boldly coloured paintings of biomorphic shapes on car bonnets. “Her colour palette is uniquely her own,” Gartenfeld says. “But she didn’t shy away from using these mass-produced industrial materials,” since that is what artists such as Donald Judd and Carl Andre were also incorporating into their subdued and austere works.

A painted car bonnet called Birth Hood (1965/2011) by Judy Chicago © Judy Chicago/Artist Rights Society (ARS)

The sculptures in the Sunset Squares series, created in 1965 and updated for the show, mix the look of Judd’s large cubes with a cheeky nod to artists of the Light and Space movement, like Robert Irwin—though the centres of the squares are cut out leaving a giant void. “She was very much involved in that artistic conversation—she was presenting a critique of the machismo of Minimalism,” Gartenfeld says.

Another more ephemeral work will be reprised for one day only in the form of a site-specific smoke installation in the museum’s sculpture garden on 23 February 2019. Her smoke pieces from the 1960s and early 1970s were originally developed as a critique of monumental architecture and what she perceived as the tendency of male land artists to destroy nature in service of their artistic legacy. Indeed, in 1970 she became the subject of Richard Serra’s ire after she lambasted him for cutting down a slew of Redwood trees for a show at the Pasadena Art Museum in California.

“To have contended with ambivalent if not completely negative reactions to her work with such high levels of ambition and belief in the importance of the themes addressed in it, is truly humbling,” Gartenfeld says. “She brings more ideas and energy to the table than any artist I’ve met. She’s always been thinking about how she fits into art history—we’re just catching up.”

The main sponsor of the show is MaxMara.

• Judy Chicago: a Reckoning, Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, 4 December-21 April 2019