The Renaissance Nude, which just opened at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and travels to London’s Royal Academy in March 2019, has been billed as an exhibition for the “#metoo” age. An article in the Telegraph quoted the Royal Academy’s Per Rumberg as saying the curators have been “very keen in the beginning to have an equal balance” of male and female nudes among the 85 objects in their show, applying what the Telegraph writer called “a makeshift gender quota” as the museum “navigates the post-metoo era”.

But there is nothing especially feminist about gender parity for nude subjects represented in exhibition works, rather that the artists included. And the idea of a quota is news to the Getty, which originated the show and oversaw the hefty catalogue that accompanies it.

“We never even thought about it,” says the show’s lead curator, Thomas Kren, the senior curator emeritus at the Getty, who began organising the show five years ago. (The Royal Academy signed on three years ago for a smaller version of the exhibition.) “This show is very much about the male nude and very much about the female nude, with great examples of both. But it’s not like we ever sat down and counted,” Kren says, noting “to present them in equal numbers doesn’t serve anything”.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Temptation of Adam and Eve (about 1510) Image courtesy of the Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie

Rather, Kren noted, both sexes are well represented because of the period chosen: 1400 to 1530, a time that saw the revival of Classical theories of male nudity and “the perfectible body” as well as the rise of female nudes in different European countries. “What we’re trying to do is put together a reasonably accurate reflection of how the nude emerged as a subject during this period,” he says.

What might surprise people outside the field is that the rise of the female nude in Europe is a relatively modern phenomenon, while the centrality of the male nude stretches further back in time to classical Roman and Greek times. And the popularity of one or the other varies dramatically by country. “In Italy in the second half of the 15th century, the focus is really the male nude, especially in Tuscany where they are working from the live model and there seemed to be restrictions about women posing naked. In France in the second half of the 15th century, the female nude is more prominent,” Kren said, chalking it up to growing “erotic” demands from male patrons.

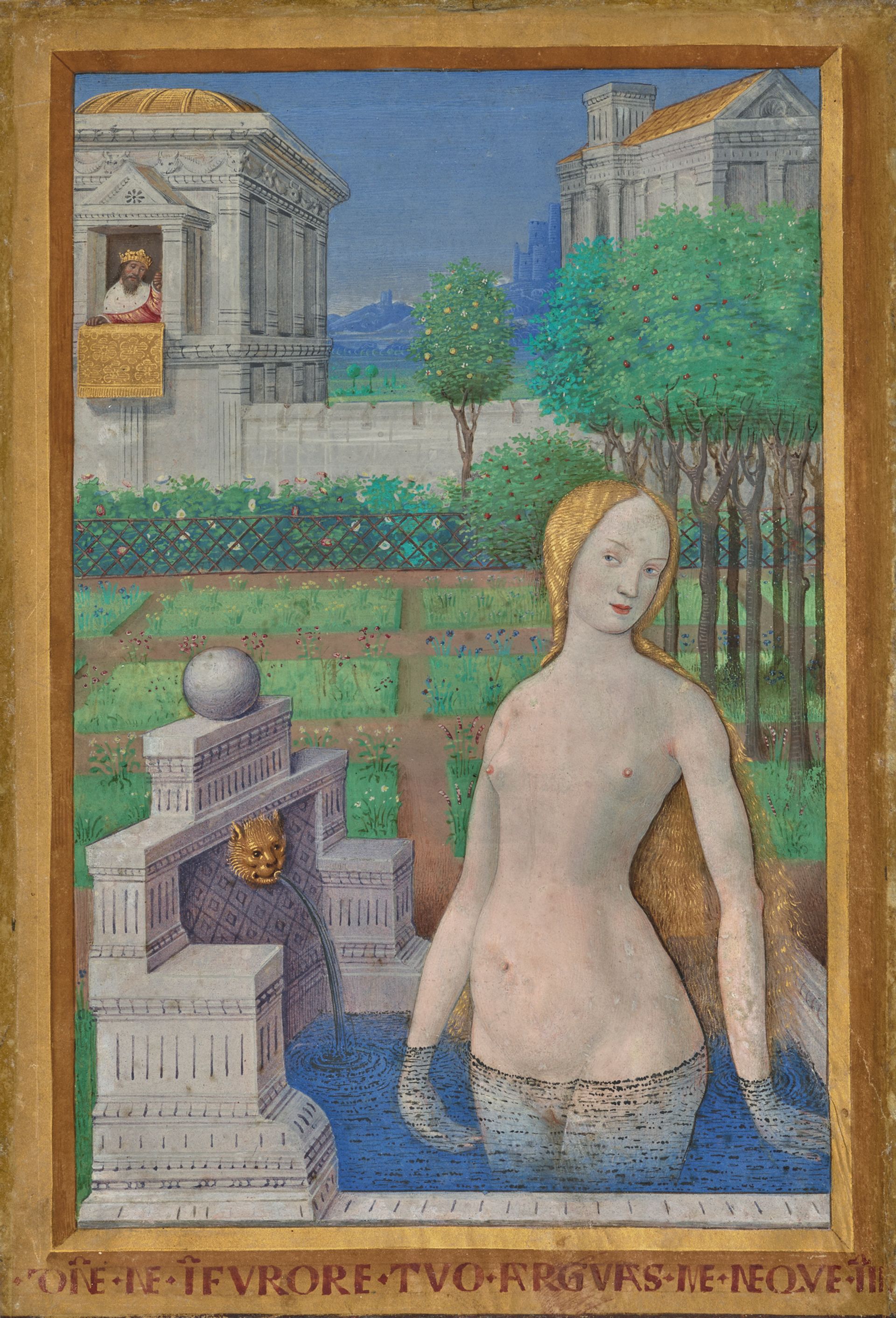

Jean Bourdichon French, Bathing Bathsheba (about 1498) leaf from the Hours of Louis XII The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In other words, the male gaze is still prevalent in this exhibition, though perhaps examined in a more thoughtful way than usual. As the art historian Jill Burke, one of the show’s curators, explains in a Guardian op-ed, the notion of the male gaze grows more complicated when you dive deeper into the actual history of sexuality. “To take 15th-century Florence as an example,” she wrote, “it’s been estimated that as many as 17,000 men were accused of sodomy from a total population of around 40-50,000—that’s the majority of Florentine men incriminated for same-sex relations. Not surprisingly, the erotic qualities of the naked male body were very much part of contemporary discourse, and it was assumed that women, as well as men, could be aroused by images of naked people of either sex.”

So why did the Royal Academy hold up this show as example of gender quotas or #metoo considerations? Per Rumberg said in an email: "I was answering a question from The Telegraph, on behalf of the curatorial team working on the exhibition here at the Royal Academy. I completely agree with Thom, we never thought about a gender quota. The show features a similar number of male and female nudes, as this is a historically accurate reflection of the period."

Kren, however, notes that he did think about gender equity more explicitly in planning the catalogue, which has seven major essays, three by women. “We were interested in having a balance of male and female voices in the catalogue because women have placed such an important role in scholarship in the area,” he said. “It wouldn’t be smart to do a show like this without getting all these viewpoints in there.”

This article was updated on 23 November to include a comment from curator Per Rumberg.