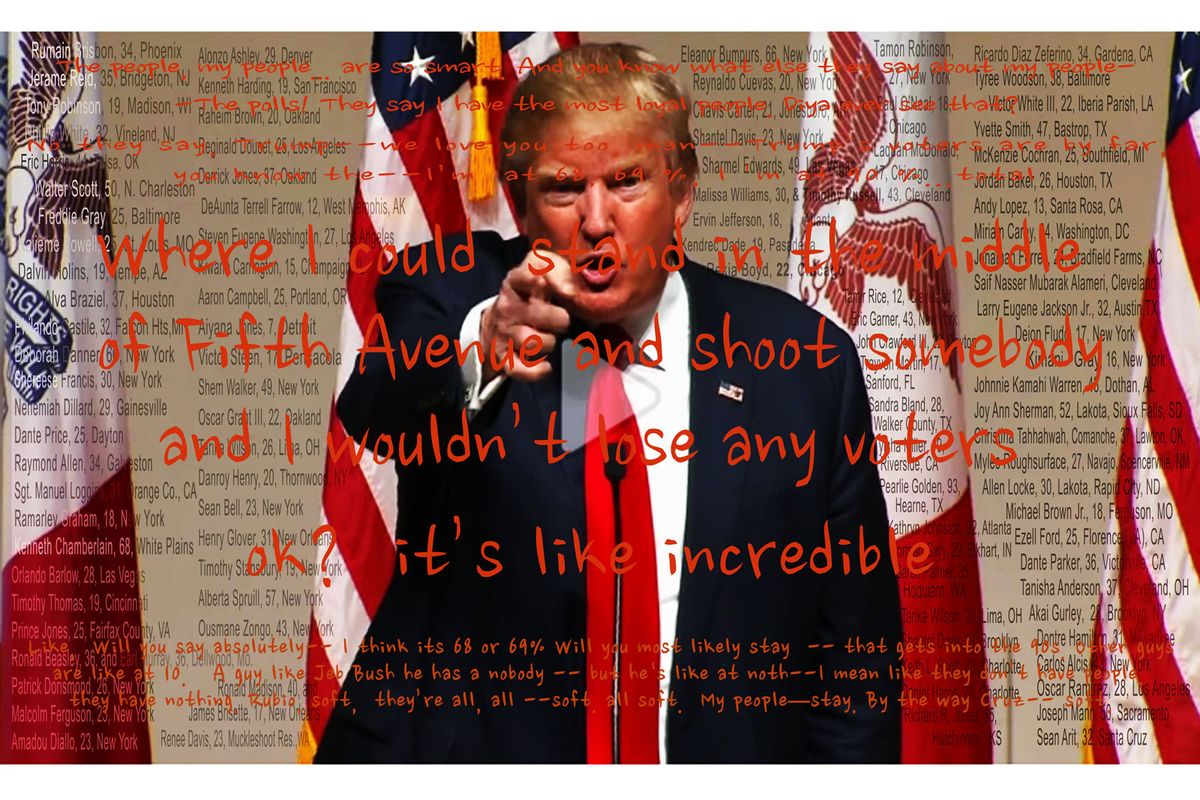

Trump is a familiar figure: a man who aspires to autocracy (after previously only aspiring to be a very rich and adored celebrity) and to the perks and privileges of kingship. He overcame his almost palpable shock and dismay at falling into the presidency, deciding to rely on others for advice while nevertheless opining and governing by whim. He makes no effort to represent all the people in the country and has refused to adopt the norms of modern governance by behaving in a civil and unifying way. His lies are overt and easily disprovable, his promises, insults, and threats are shocking, his self–interest and vindictiveness equally clear.

His base of support has remained largely stable, consisting of white rural voters, more male than female, and very rich elites; the former because his authoritarian promises to save their declining fortunes in life are supported by the extreme right-wing media that aids and abets his lies and distortions, and the latter because he governs on their behalf.

Demographic and labour shifts in the US have produced well-educated city dwellers and suburbanites with professional and other middle-class jobs. But the movement of people to cities has left behind large regions with many poor and working-class white residents with at most a high-school education. Up until the late 1960s, they were generally securely employed, often in factory work.

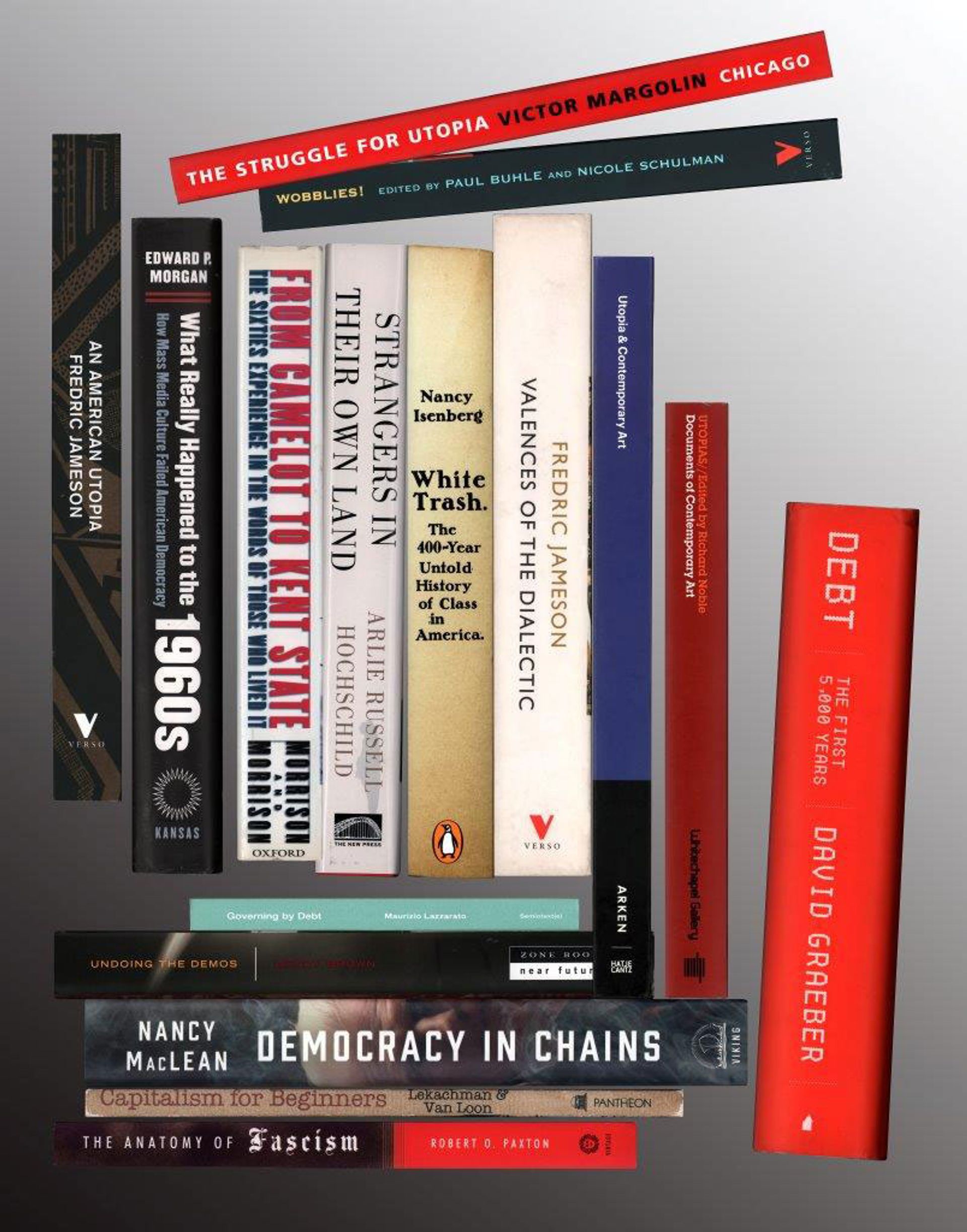

Martha Rosler, Capitalism, Democracy (2018), from the series Off the Shelf (2008-18) © Martha Rosler

Trump has crafted his campaigns to address that abandoned class of workers in decline who are desperate for a way out but are stuck in economically shattered regions with little prospect of growth. He also appeals to predominantly white, often small-town Christian conservatives, evangelicals who fear the challenges to their certainties about life that have come out of the powerful social movements of recent decades. This latter group are intent, like the wealthy, on getting their agenda into law and are steadfastly unconcerned with the issues of character that have, interestingly, led long-time “movement” conservative ideologues to distance themselves from, and even to denounce, Trump.

Other parts of the electorate, largely people of colour, live in any or all of these same areas. Large numbers of people of colour do not vote, and many are aggressively marginalised. Since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s, when millions mobilised and even died for the right to vote, they have been specifically and increasingly targeted for electoral disenfranchisement by Republicans for being reliably Democratic “big tent” voters.

This year, the Democratic senators up for re-election were largely in Trump-supporting states, and the Democrats lost Senate seats there. But the surge of Democratic seats won in the House reflects the currents of resistance that were building even before Trump’s election, but which manifested themselves publicly immediately afterward and have not abated since.

Democrats have relied on highly educated professional-class voters and idealistic celebrities to support them electorally, and increasingly on what the Republicans have denounced as identity politics, aiming to empower people beset by social stigma and campaigns of vilification and even criminalisation: African Americans and LGBTQI people, but also (of course) women, and Latinx, and more recently, Asian, South Asian, Native American, and refugee populations. The party has also made efforts to create universal health care and to raise educational and economic levels.

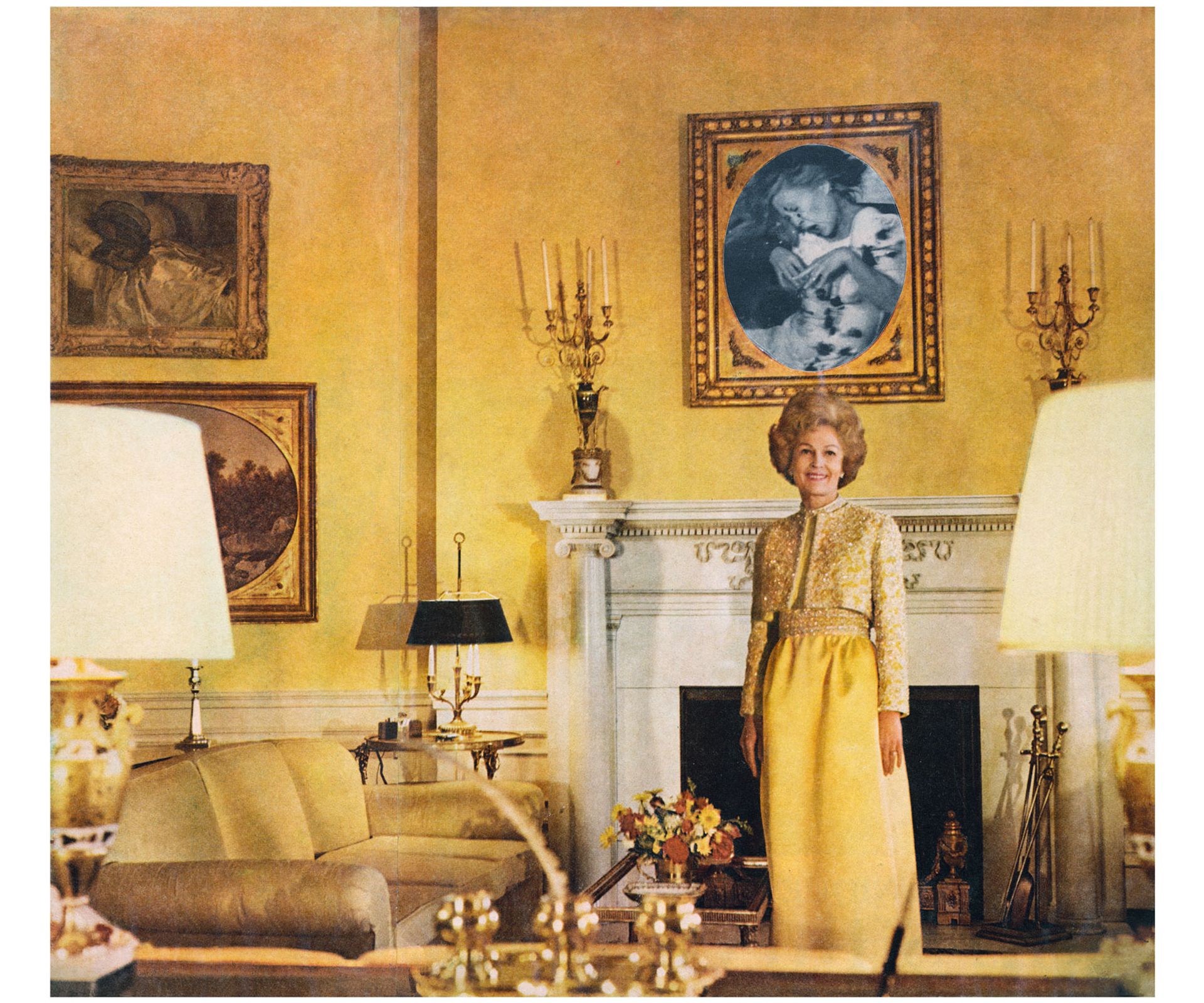

Martha Rosler, First Lady (Pat Nixon), from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, (around 1967-72) © Martha Rosler. Courtesy of the artist, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne

The mid-terms were indeed, as widely predicted, a referendum on Trump as a man and as a leader. Women, many infuriated by Trump’s victory and his long history of vile and shocking sexism, had begun organising immediately upon his election, and during these mid-terms women ran for office in large numbers, resulting in a big increase in the number of women representatives in the House, the vast majority of them Democrats. In 2016, about half of white women voters supported Trump, while about 95% of black women voters backed Hillary Clinton. Educated suburban white women also began to move away from Trump very soon after his election, and they organised opposition groups, some of them secret. Women of colour remained in the forefront of anti-Trump resistance—as they have for decades been leaders in social struggles.

These mid-term elections—with the understanding that most of the gains mentioned were in large part in cities and suburbs—brought the country, via the Democrats, many firsts for women, many of whom had never before considered a political career. A third of the female House candidates were women of colour. Several women were elected as governors for their states, including for the first time several in the country’s heartland, not usually Democratic territory. It also brought the first black women representatives in several states; the first two Muslim women in the House; the first two Native American women, one of them a lesbian; the first two Texas Latinas; the first four women in the Pennsylvania delegation; the two youngest women ever elected to the House; immigrants and even at least one Dreamer (a person brought illegally to the US as a child, usually from a Latin American country); Asian women representatives; an Iranian-American woman; several women military veterans. The elections also brought the first openly gay man as a state governor. There were agonising near-wins in Texas and elsewhere, and in Georgia and Florida, where the election results have not yet been officially declared and are under contest, the apparently defeated Democrats are African-Americans. It is an understatement to say that the progressive base is “energised”.

The mid-terms also brought a stunning victory, in a ballot measure in Trump-voting Florida, for the return of voting rights to many convicted felons after their release from prison. A ballot measure in also highly Trumpian Louisiana overturned a law allowing the conviction of people, and even their sentencing to death, on the basis of non-unanimous guilty verdicts. A Massachusetts ballot measure upheld transgender equality, in the face of the president’s recent effort to define transgender identity out of existence. These ballot measures, and others, point to the “progressive” intentions of a majority of voters even in states that may have failed to elect Democrats.

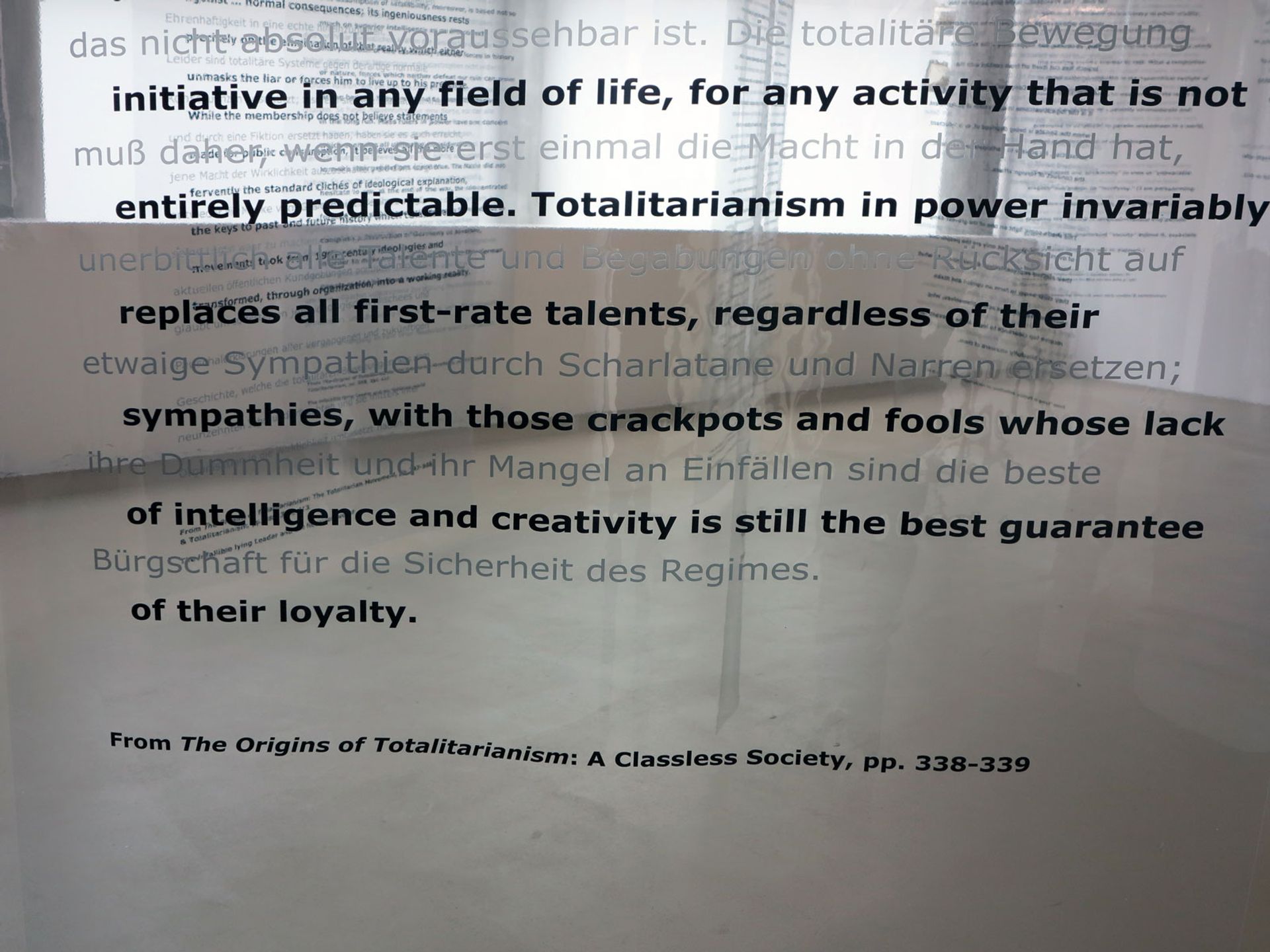

Martha Rosler, detail of Reading Hannah Arendt (Politically, for an Artist in the 21st Century) (2006), installation with excerpts from Hannah Arendt’s writings, in English and German, on transparent acetate panels © Martha Rosler. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne

But the bolstering of Republican Senate control allowed the president to fire his Attorney General less than a day after the elections, to protect himself from the investigations likely to ensue from the Democrats’ taking of the House, renewing his effort to pretend that neither his own finances nor his possibly criminal liaisons with the Russian state are legitimate targets of investigation. It also prompted him to engage in a frontal attack on a prominent mainstream CNN reporter of Latinx origin, accuse an African American journalist of being a racist and rudely refuse to take a question from another black woman. And this is where we stand now: possibly on the brink of a constitutional crisis.

I hope that Democratic and progressive forces recognise this moment as one in which we must increase our efforts to organise, demonstrate and advocate for the economic and social policies that we continue to demand and require. And to support ever more diverse and progressive candidates—especially women—for elective offices. We are still far below equitable numbers.

• Martha Rosler is a New York-based artist who has been creating work about political and social issues since the 1960s. Her show Martha Rosler: Irrespective is on view at the Jewish Museum until 3 March 2019.