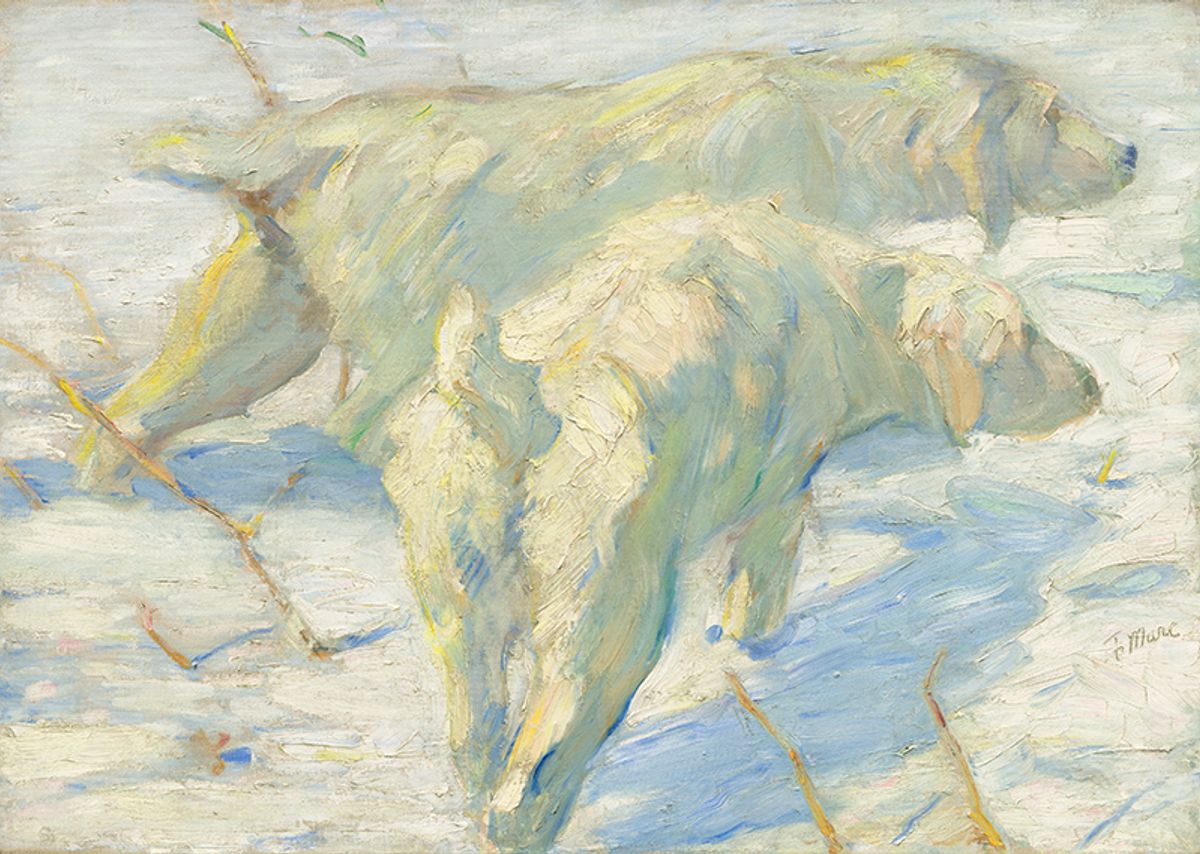

The Neue Galerie’s exhibition Franz Marc and August Macke: 1909-14 (until 21 January 2019), which pairs works by these two founding members of the German Expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter, “is really about the power of friendship”, the museum’s president Ronald Lauder writes in the catalogue. It traces the works of the two artists, who met each other in Munich in 1910, in a roughly chronological presentation, starting with a standout, sympathetic portrait of Marc by Macke (1910). Above all, it is a display of stunning and often touching art, like Macke’s depictions of his young son Walther and a still-life of his toys, and beautiful country and leisure scenes. Marc’s colourful animal pictures, like the exuberant 1911 work The Yellow Cow (on loan from the nearby Guggenheim), are always a joy to see. But his slightly earlier animal works, in a gentler palette, are just as delightful: Interior Forest with Deer (1909) hides the white-spotted creatures among the soft pinks, blues and yellows of the woods, while the wobbly-legged Foals at Pasture (1909) dance playfully across the canvas and Siberian Sheepdogs (1910) conveys the animals' snout-led curiosity. The show leaves us wondering what other gorgeous work Marc and Macke might have left the world had they not been killed in the First World War.

In 1906, heeding the call of a spirit summoned in a séance, the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) broke with academic tradition and began creating a series of 193 boldly colourful paintings in which she invented an abstract vocabulary blending biomorphic and geometric forms. She completed them in 1915, and later wrote of her desire to see them reside in a circular temple, where visitors would ascend a spiralling contemplative path. See the artist’s vision come to light on the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s looping ramps in the exhibition Hilma af Klint: Painting for the Future. It showcases the breakthrough years 1906-20, delving into Af Klint’s relationship to Modernism and her interest in theosophy, spirituality, the natural sciences and atomic particles. “Her existence and her work bring all kinds of questions to the story we tell about early 20th-century abstraction, the way people worked, and different intellectual thoughts and theories that they were engaged in,” says the Guggenheim’s director of collections and senior curator, Tracey Bashkoff. “The Modernists whom we call the pioneers of abstraction were making their strides six or seven years later than she was.”

“I’m excited about getting a chance to revisit the New York art scene after almost 40 years,” says the Washington, DC-based artist James Phillips, who has a solo exhibition of his vibrant, energetic paintings and works on paper, Radical Abstraction: 1970 to the Present (until 1 December), at Kravets Wehby Gallery. Phillips, who joined the Harlem-based Weusi Group in 1969 and the collective AfriCOBRA in 1972, says that his works counter “stereotype images that Hollywood and the Minstrel try to paint about people of colour”. His works are grounded in a “figurative element” that “becomes a point of departure to abstraction”, he says, and cites myriad influences, including patterns from traditional African art and African American quilts, Mandala paintings, the work of contemporary African artists like the Nigerian artist Twins Seven Seven and Aboriginal Australian art. Music by artists such as John Coltrane and Don Cherry “gives me the kind of call and response” aesthetic, Phillips says—you can feel it pulsating through the paintings and works on paper in the show. Colour is crucial, he says, and complex: they carry different symbolic meanings across cultures, and “you have to learn how to play between these different colours so they don’t contradict each other”.