In The Art Dealers, an oral history of New York gallerists in the early 1980s, the Greek-born dealer Alexander Iolas says: “The boy is a very important artist, Andy, because he helped America.”

That was Andy Warhol, of course—in the art world there’s only one Andy. He’s been good not just for the country but also the art market, art history and scene-makers everywhere. And anyone with half an eye who visits the Whitney Museum’s survey of this singular artist’s career ought to be able to see why.

From the show’s first moments, which envelop viewers in a room papered, floor-to-ceiling, with Warhol’s pink-and-yellow cow wallpaper and plastered with flower paintings just as colorful, Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again is exciting. Even, or especially, for those who think they know all there is to know about him.

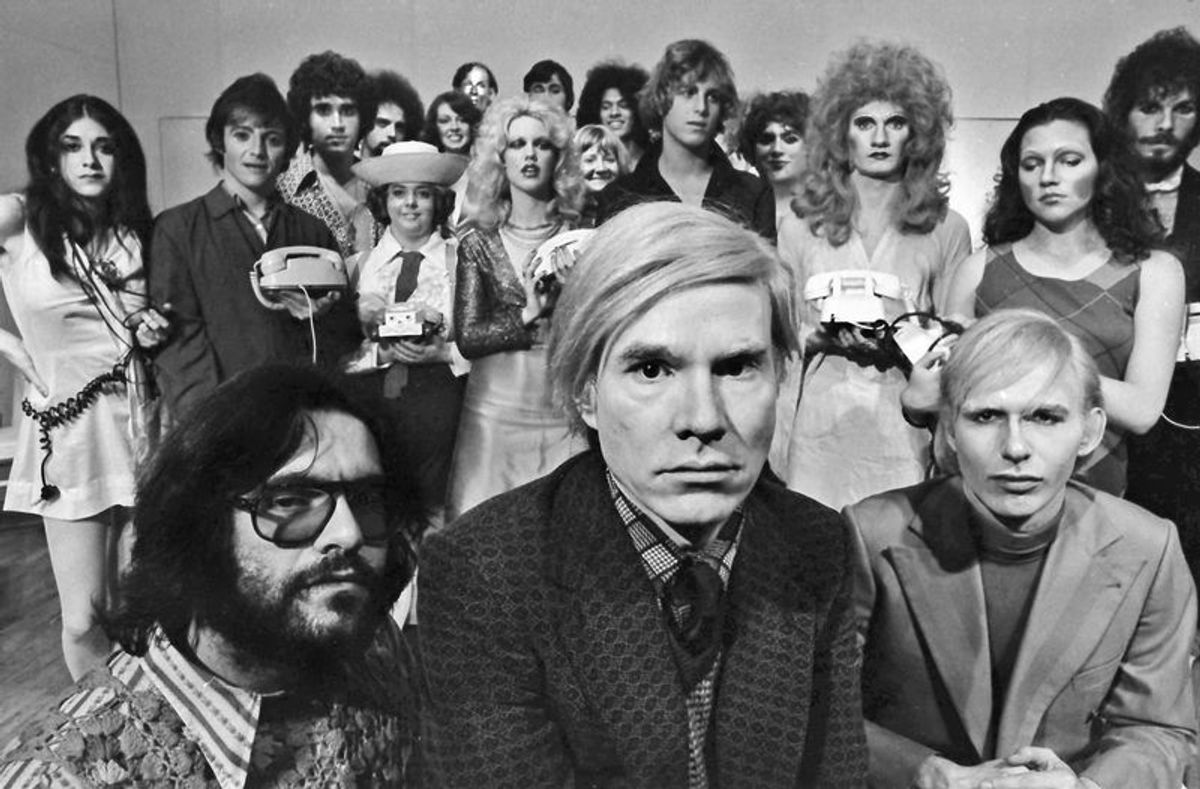

“This is the best-installed Andy show ever. Ever,” said the Warholian artist Deborah Kass, emerging from the huge crowd that stepped out for the election-night, invitational opening. “I was here last night and this morning, and I’m coming back tomorrow morning to do a breakfast panel,” said Vincent Fremont, the one-time Factory manager who inspired and produced Andy Warhol’s TV. “We’re getting paid,” Fremont added, “so it’s all right. Bank of America, thank you.”

The bank may have helped to sponsor the show, but the credit for what already looked like a runaway success goes to curator Donna De Salvo. She has given museum professionals everywhere a model exhibition on an epic scale. “Donna De Salvo!” enthused the Museum of Modern Art curator Yasmil Raymond. “A-may-zing! We all need to take notes and be humble in her presence.”

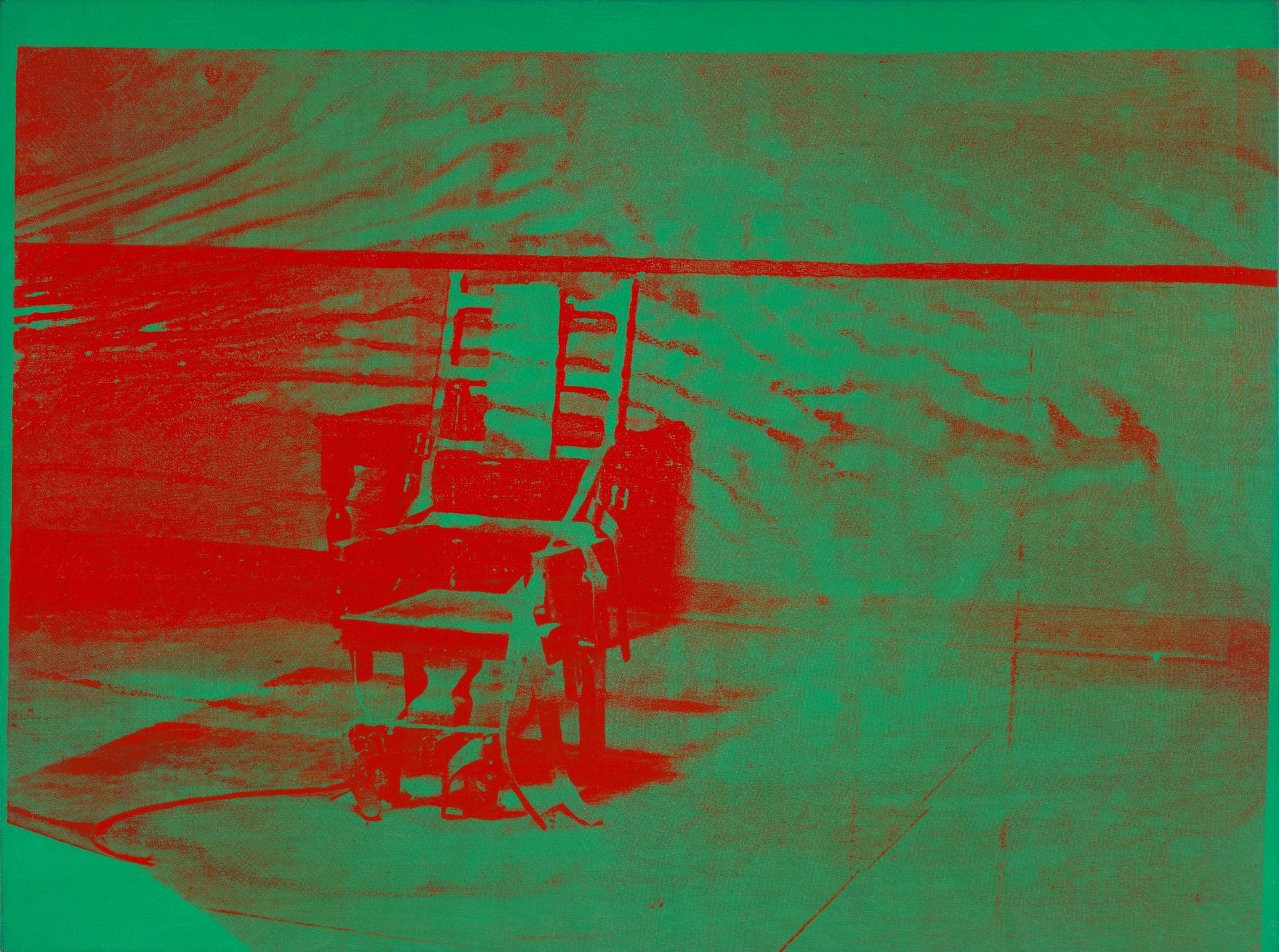

Andy Warhol, Big Electric Chair (1967–68) © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This is De Salvo’s fourth Warhol exhibition, following two shows at Dia in 1986 and 1989 (showing the Disaster series and hand-painted Pop paintings), and early works at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery in 1989. She may know the material better than anyone.

A sculpture of coloured Mylar rolls stacked inside a thick, Plexiglass case that struck me as a cross between Donald Judd and Jeff Koons was quite a startling sight. Another discovery was Warhol’s take on Duchamp’s Large Glass, in the form of freestanding window panes imprinted with an image of John Giorno from the 1964 film, Sleep.

“I love my experimentation room,” De Salvo said, speaking between frequent interruptions from admirers. “Andy was a great sponge, and a great social observer as well. I think he understood major contradictions in American life and the oppositions—innovation and conformity—that define the American character.” Ironically, she reflected, European collectors and curators who saw him through their own filters were first to buy his work, while his own country dismissed it as lightweight pap.

Now, in the age of Trump, people appreciate Warhol’s deployment of his fetishising interests in film, magazine and book publishing, television and advertising as the “business artist” he aspired to become. Yet the evidence on the walls at the Whitney show him to be all about the art of art—a restlessly hands-on exploiter of every visual opportunity, in every medium, offered by the sensational, glamorous or dismaying. He was a wicked voyeur, a gay man who had a horror of physical human contact and was an obsessive hoarder who was so insecure that he could never stop working, or shopping, for ideas as well as people and things.

De Salvo brings together telling examples from every phase of Warhol’s production, from early drawings and shoe collages (gorgeous) to the Marilyn, Elvis and Brando Pop paintings, portraits and self-portraits, the contents of one of his Time Capsules, Interview magazines, a colossal portrait of Mao, collaborations with Jean-Michel Basquiat, screen tests and other films—perhaps his most influential work—arranged in unpredictable ways that make emotional, aesthetic and historical sense of this formerly inscrutable artist.

In the final gallery, Warhol’s varied approaches to abstract painting play off each other to enthralling advantage. For example, placing the 36-foot long “reversal” painting, Sixty-Three White Mona Lisas (1979), opposite a Last Supper overlaid with a camouflage pattern, was a masterstroke.

Iolas said of Warhol: “He is an amazing person, and probably someday he will be considered a saint.” Thankfully, Donna De Salvo has brought him down to earth, where we can touch him at last.

• Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again, the Whitney Museum of American Art, 12 November-31 March 2019