The grid of colourful faces of celebrities and socialites on one gallery wall at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Andy Warhol (1928-87) retrospective will resemble nothing so much as an Instagram montage. Yet the images are 30 to 50 years old. For Donna De Salvo, the exhibition’s curator, the array of silkscreen portraits underlines just how prophetic Warhol was in his use of technology, photography and serial formats.

“In an age of Instagram and so many other social media platforms, Warhol’s famous statement ‘everyone will be famous for 15 minutes’—which is probably now 15 seconds—rings incredibly true,” says De Salvo, the museum’s deputy director for international initiatives and senior curator. She hopes that the exhibition, the first Warhol retrospective organised by a US institution since the Museum of Modern Art mounted one in 1989, will therefore prove intriguing to a young generation.

But the show aims to do far more than connect viewers with 1960s portraits of figures like Marilyn Monroe or Elizabeth Taylor. With more than 350 works spanning four decades, it aims to make the case that Warhol’s creativity remained undiminished after an assassination attempt in which he was badly wounded in 1968. The show celebrates innovations such as the artist’s ghostly still-lifes, art historical appropriations and abstract camouflage paintings of the 1980s, which at the time drew a lacklustre critical reception. And it delves into Warhol’s beginnings as a commercial illustrator and artist in the 1950s, arguing that the aura of desire in his drawings of products like high heels paved the way for his later work and his own mystique.

The aura of desire in his drawings of products like high heels paved the way for later work

The sprawling exhibition, the largest show that the Whitney has ever devoted to a single artist in its Gansevoort Street building, was not easy to pull off. De Salvo had to persuade institutions and private collectors to part with fragile works jointly valued at hundreds of millions of dollars. To cover the enormous insurance costs, the museum arranged to have the show indemnified by the US government’s Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

De Salvo’s tenacity is rooted both in her eagerness to see Warhol’s full career given its due and a personal connection to the artist, whom she met in the mid-1980s when she curated two shows of his early work for the Dia Art Foundation in SoHo. (Dia is exhibiting part of Warhol’s Shadows series of canvases from 1978-79 at Calvin Klein’s Manhattan headquarters in tandem with the Whitney show.)

“I found him a very open, shy, interested artist” in what evolved into “a really fantastic conversation” about Warhol’s artistic process, she says. The artist’s untimely death aged 58—following a gallbladder operation—saddened her not just because that conversation ended, but because the world would not see “where his work would have gone if he had lived”.

The show celebrates the entire range of Warhol’s art, including not only paintings but prints, drawings, video and photographs. Selections from his voluminous 16-mm film oeuvre will be screened in a black-box gallery and a theatre at the museum. Many of these films are also a kind of portraiture, De Salvo says, in their portrayal of the idiosyncratic personalities from Warhol’s famed hangout and production site the Factory.

A consistent thread through the exhibition is the enigmatic quality of Warhol’s work. Mystery prevails, whether it is a silkscreened image of an electric chair shaded in lavender from his Death and Disaster series; his still-lifes of a hammer and sickle (variously paired with a vibrator, a Big Mac or Wonder Bread); or a rendition of Leonardo’s Last Supper overlaid with a camouflage pattern. “I’ve always believed that the test of a great work of art is that no matter how many times you go back to it, you can’t completely figure it out,” De Salvo says. “I think that’s the case with Warhol.”

The show will travel to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago. Bank of America is the sponsor of the show’s national tour; the exhibition in New York is sponsored by Calvin Klein and Delta, among others.

• Andy Warhol: from A to B and Back Again, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 12 November-31 March 2019

• To hear a in-depth interview with the curator of the Whitney show Donna de Salvo, listen to The Art Newspaper podcast

Curator Donna De Salvo on three key works

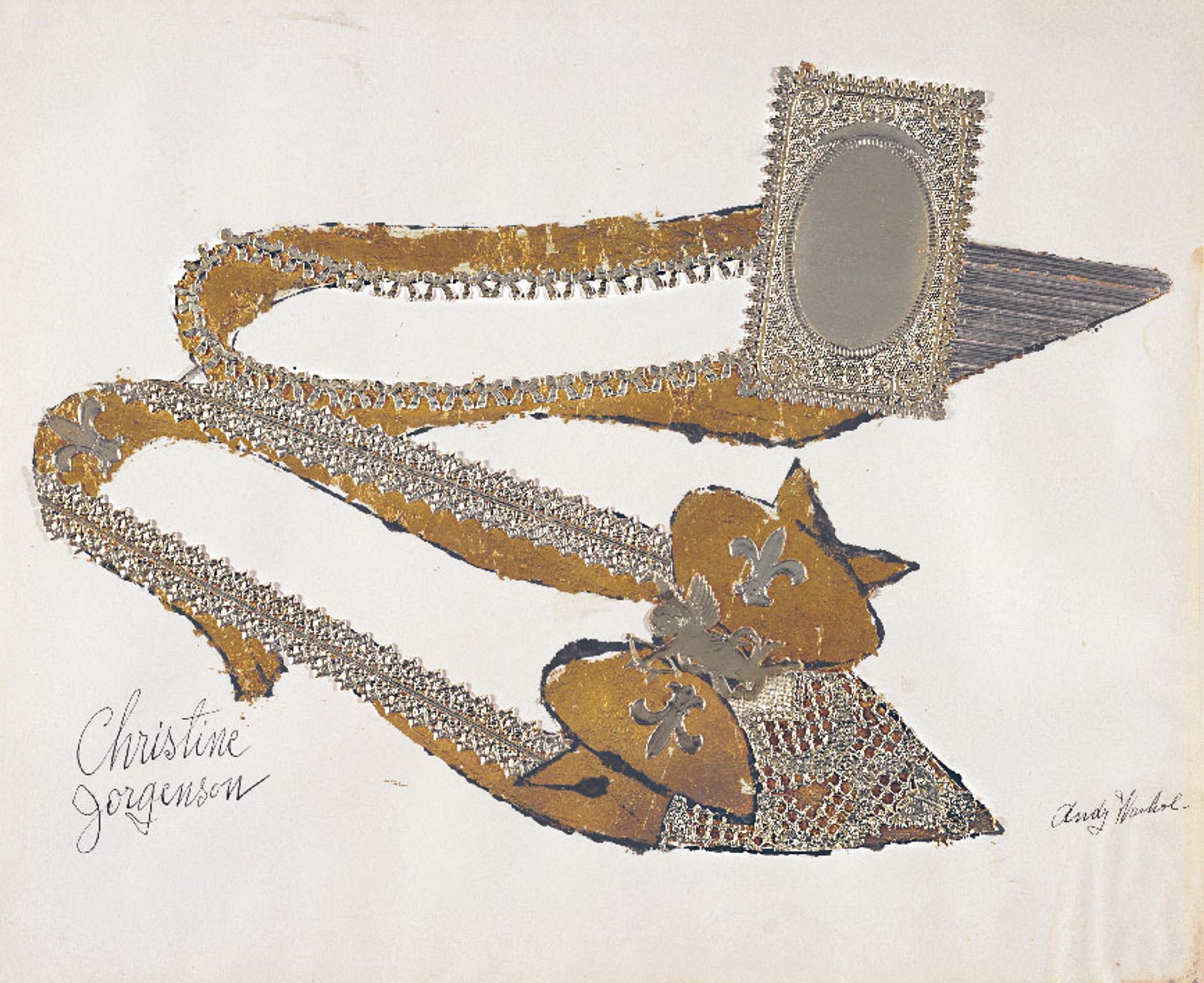

Christine Jorgenson (1956) © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/Artists Rights Society

Christine Jorgenson (1956)

“[After moving to New York in 1949] Warhol very readily got a job at Glamour magazine, because he had this great proficiency at drawing. I think that throughout the 1950s, he was able to see first-hand the mechanics of visual communication, how images are put together, how desire is created in a product, whether it’s a shoe or a pharmaceutical. So to be part of that and work with art directors—many extremely sophisticated and well-trained themselves, some in the Bauhaus—he had a front-row seat and an engagement with the process of how the art director transmits their idea.”

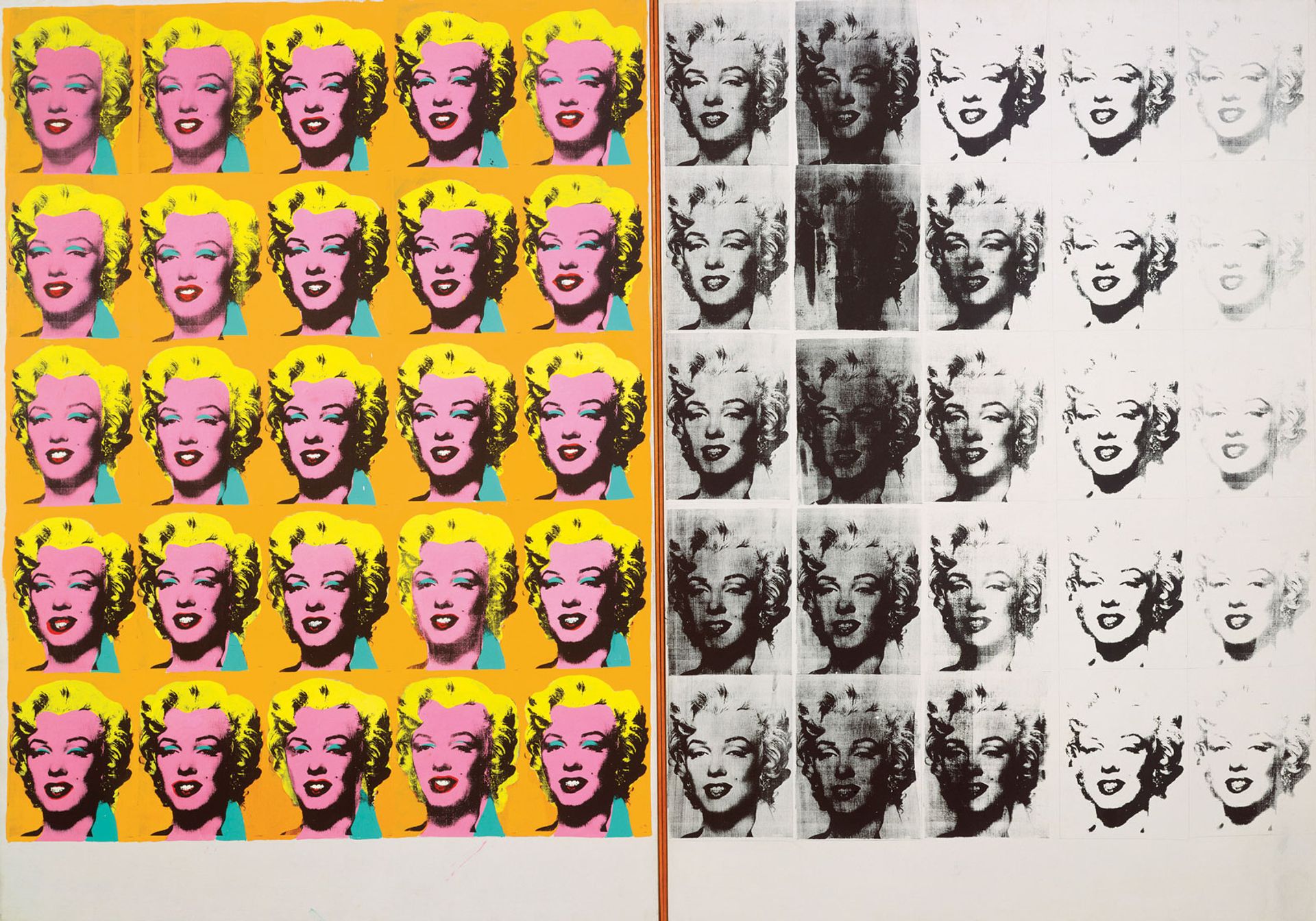

Marilyn Diptych (1962) Tate

Marilyn Diptych (1962)

“In some ways, Warhol’s move to the silkscreen seems inevitable. What differentiates it from earlier [work is] the insertion or the use of the photograph, because now you’re moving [on] from something he draws himself. There are some silkscreens that are based on drawings. But to use the photo silkscreen to make painting is really when form and content come together—he’s using the very technique through which these images are disseminated to make the painting. And that’s the radical shift.”

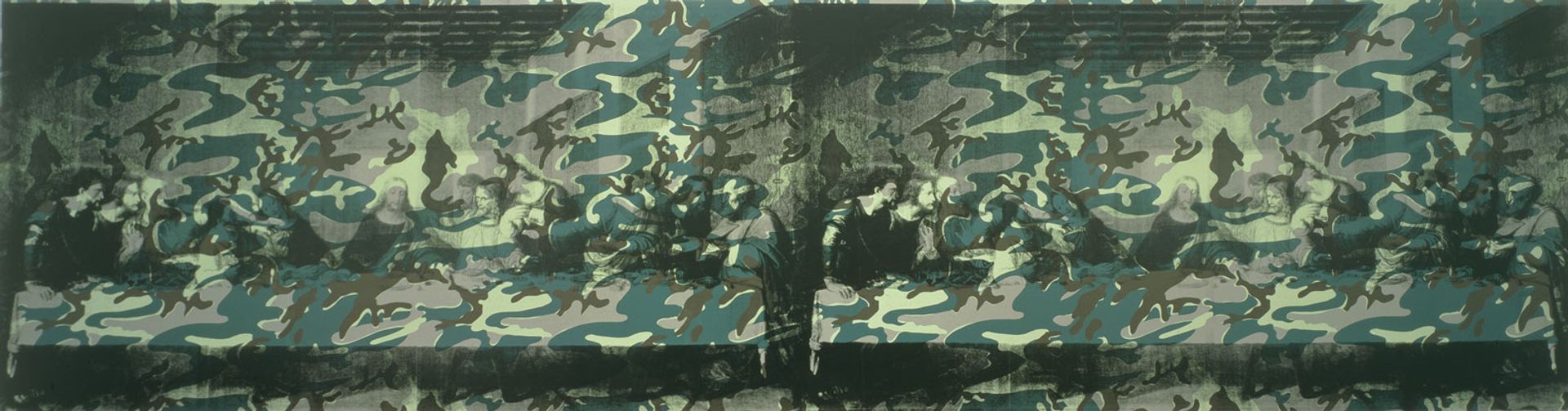

Camouflage Last Supper (1986) © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/Artists Rights Society

Camouflage Last Supper (1986)

“I think one of the most complex topics Warhol takes on is Leonardo’s Last Supper. I really believe, fundamentally, that what Warhol’s whole project comes to, is the illusion. At the time [he made the work], there was tremendous debate about restoring [Leonardo’s Last Supper]. Should it be left as it is? Warhol even says he preferred it in its deteriorated state. He’s able to somehow bring together the world of popular culture and the world of art. [He shows us] that somehow we’re looking at a painting, but we’re [also] looking at a painting about something: an object [or] a brand that’s trying to get us to believe something, to buy [into] it.”