On Monday morning, nearing the end of what is likely the most heated mid-term election cycle in modern history, a busload of around 50 volunteers left from Karma gallery in New York’s East Village. The artists, art world professionals and friends of the gallery aboard the bus were headed for Staten Island to knock on doors for the Democratic candidate for Congress, Max Rose, who has a strong chance of unseating the incumbent Republican representative, Dan Donovan, in Tuesday’s elections (6 November).

The bus was one of several departing from galleries in New York and Los Angeles, all organised by the left-wing grassroots organisation Swing Left and destined for nearby swing districts. Other galleries participating include Canada, Blum & Poe and Night gallery. The initiative is one part of a larger effort to mobilise the cultural and financial capital and left-leaning energies of the art world to get out the vote for Democrats.

For Brendan Dugan, Karma founder and owner, the decision to lend the gallery’s name and space to liberal efforts to take back Congress was a no-brainer—and one that came with little risk of alienating any potential right-leaning clients. “I think that everyone is looking for ways that they can simply or quietly help and be involved,” he says. “And I think at this point, it’s understood that people have different views.”

Karma has also contributed to the effort by producing editions for sale by Downtown for Democracy, a New York-based cultural political action committee (PAC) founded in 2003 during the presidency of George W. Bush and resuscitated following the election of Donald Trump. The PAC has been busy over the past two years producing and selling editions by prominent artists like Richard Prince, Cecily Brown and Katherine Bernhardt in order to raise funds for progressive advertising campaigns across the US that are intended to engage millennial voters.

The money raised has been channeled back into images and videos produced by artists like Petra Cortright and Danielle Levitt and targeted at 18 to 24 year olds, a demographic that is typically “off the radar” politically, according to Gina Nanni, one of the PAC’s primary organisers and advisors. Young voters have historically turned out in very low numbers for elections, especially in mid-terms.

Nanni says the organisation has had little trouble finding galleries willing to lend a hand: “Today, it’s perhaps even easier because people are so shocked by what’s happened to the country. There are very, very few people in the art world who don’t feel the same way. If anything, they’re going to be collectors from the Midwest. Dealers have been very supportive.”

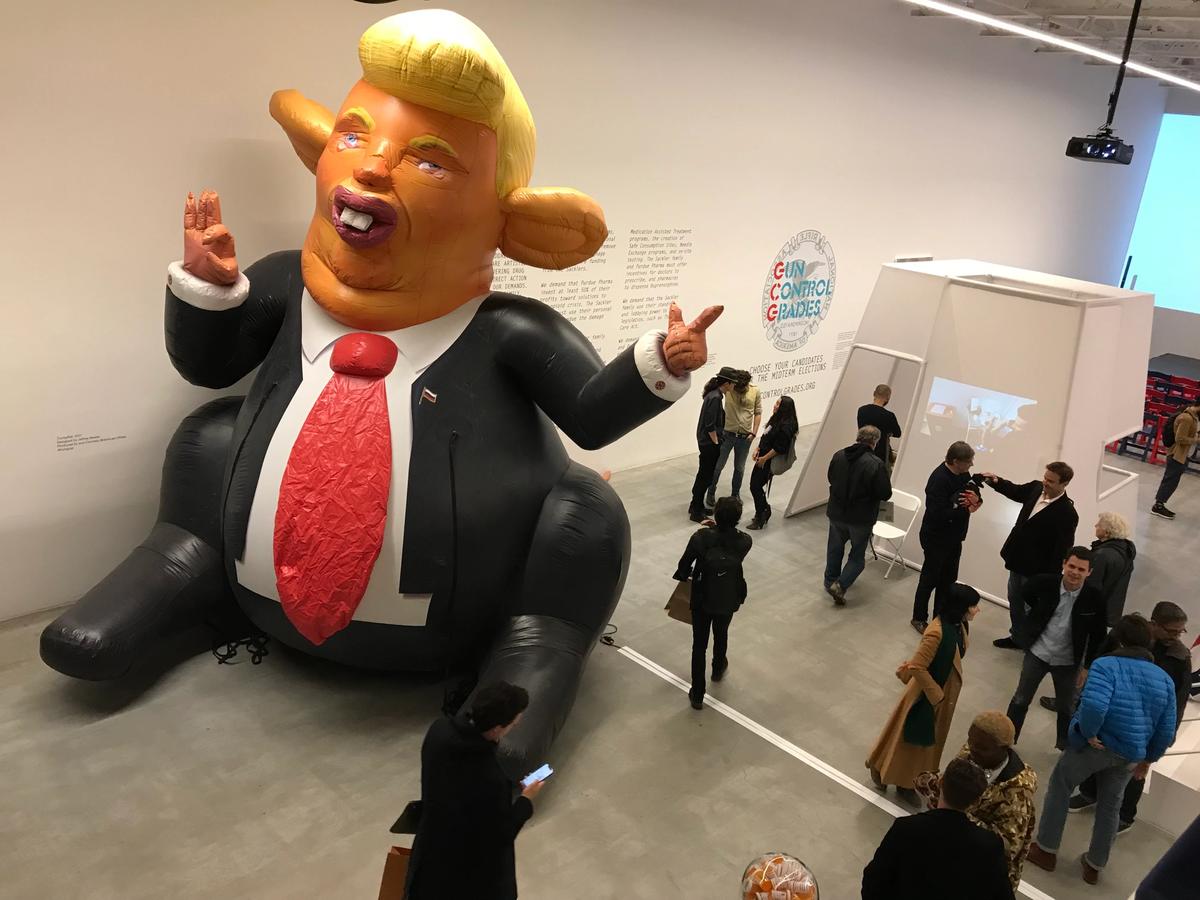

Jeffrey Deitch also offered up his gallery space in Soho to Downtown for Democracy, which organised an activist-artist bonanza titled Protest Factory, including BravinLee program's recognisable giant inflatable Trump Rat balloon, poster-painting sessions led by artists such as Marilyn Minter and the sale of a limited edition t-shirt produced by artist Richard Prince and clothing cult brand Supreme—the company’s first political engagement—featuring a composite face of all the women that have accused President Trump of sexual misconduct.

“This is not a normal time,” Deitch says. “It’s not a time for complacency. Every gallery, business, workplace where there are people who are concerned about the challenges to democracy that are happening right now should be doing something like this. We’re participating in the American political process; we’re not doing anything radical. This is how democracy functions.”

Even as they lined up to support left-wing groups, affirming the art world’s long-held liberal sympathies, dealers struck a decidedly bipartisan, patriotic note on the eve of the mid-terms. “Basically what we’re saying is: people should go vote,” Dugan says. “I don’t care who you’re voting for, or what your policies or beliefs are; you should go vote. I think there’s something really positive about that.”