Cultural patrimony laws today are overstretched, often failing to take into consideration artists’ mobile, transnational lives and careers, or the fact that works of art can live on in different countries long after they were made. The root of the problem is the concept of national patrimony, which views culture as something innate, inherited and owned by one country, rather than part of a shared world heritage.

Take, for instance, the long-contested Statue of a Victorious Youth or Getty Bronze, created in Greece in 300BC-100BC, found in international waters by Italian fishermen in 1964, and resident at the Getty Villa in Malibu, California, for nearly half a century. To which country does it belong? (In June, an Italian court ordered the museum to forfeit the work to Italy; the Getty said it would appeal.)

I recently consulted on the case of a contested painting by Giorgio De Chirico, who worked in and was inspired by Germany, Italy and France. In 1927, he wrote: “As a painter and as a modern spirit, I feel more in harmony in France than in Italy.” Today, however, his work is considered part of Italian patrimony.

The question of national belonging can extend to style and materials. Leonardo da Vinci took his famous sfumato technique from Northern European art. Can his works, therefore, be claimed by Northern Europe? He imported lapis lazuli from Afghanistan for blue pigment. Does this give Afghanistan a right to ownership?

There are artists who have not been appropriated by their countries of origin. Brancusi, Giacometti and Lipschitz were born in Romania, Switzerland and Lithuania, respectively, but lived and worked in France. The opportunity to share their works seems acceptable to their home countries. The enduring internationalism of these artists is part of their modernity and lasting appeal.

We need to rethink our perceptions of an artist or a cultural object as having a single, unified or homogenous heritage. Rather than patrimony, perhaps cultural “matrimony” would be a more useful notion.

The word patrimony goes back to “pater”, father in Latin, and refers historically to the property of the church or the spiritual legacy of Christ, from the Latin “patrimonium”, an inheritance from a male ancestor. In a marriage, patrimony is defined as that which is inherited. Patrimony gives a sense of belonging and strives not to be dispersed; it is a concept that protects but also limits culture.

“Matrimony” relates to “matrem” or the mother, suggesting something brought into a marriage, such as the gift of a dowry and the gift of life. A matrimonial approach would emphasise a shared cultural heritage that enables objects to be part of transnational relationships, in a manner that respects artists’ mobile identities. A matrimonial approach opens up fertile new potential for trust and synergy among diverse entities.

The contested Getty Bronze, found in international waters Photo: Wtin

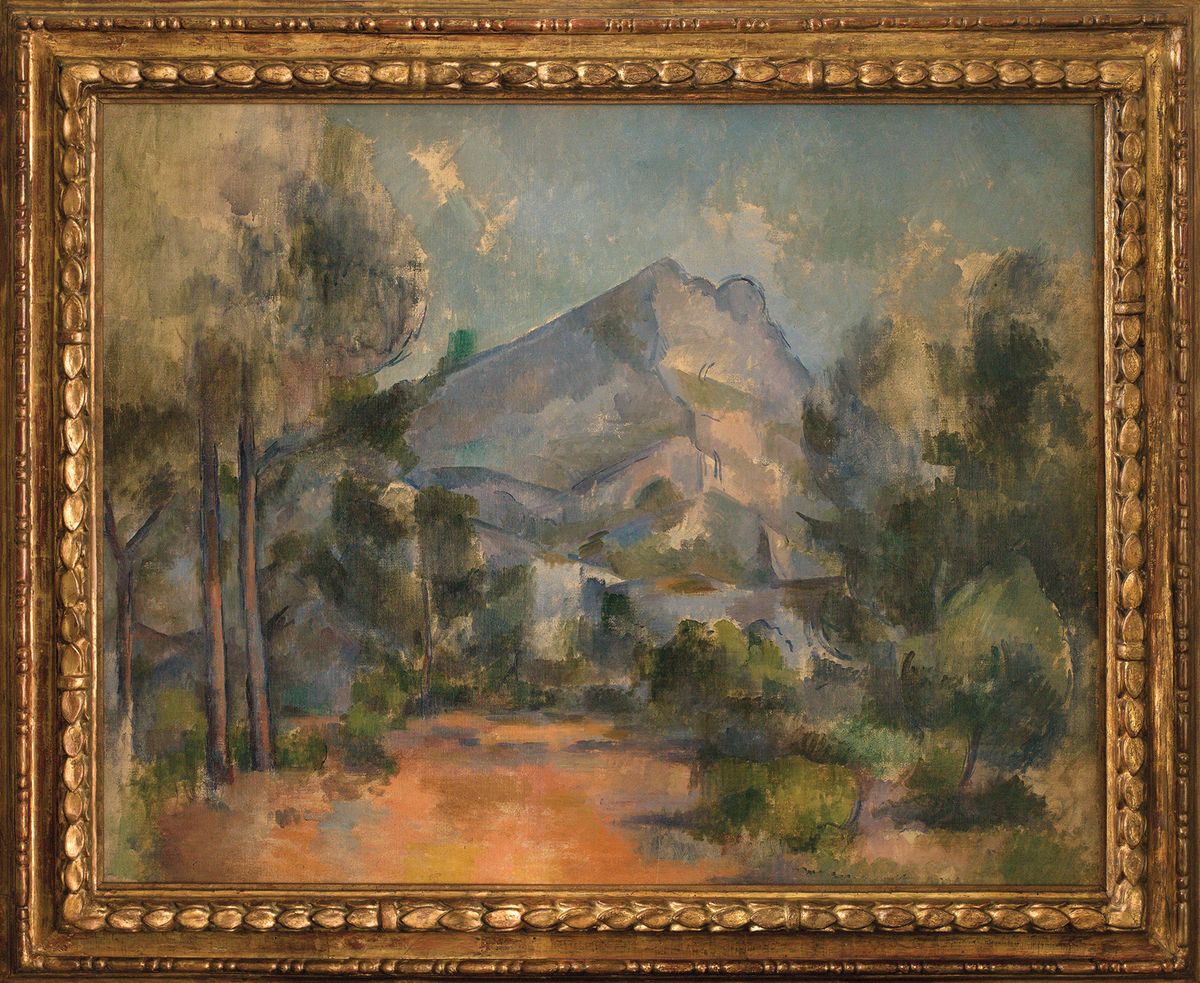

We are already witnessing the emergence of such models, which will require fine-tuning as they evolve. The Benin Dialogue Group of European museums is planning a permanent display in Nigeria of Benin works looted by the British, on rotating loan. In July, the family of Paul Cézanne reached an agreement with the Kunstmuseum Bern to share a disputed painting from the hoard of Cornelius Gurlitt, Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1897), between the Swiss museum and the Musée Granet in Aix-en Provence. The artist’s great-grandson said the deal, in which no money changed hands, was “in the spirit of Swiss-French friendship”.

In response to conservation concerns surrounding the circulation of works of art, a matrimonial approach to knowledge-sharing could enable institutions to forge new standards of best practice.

I believe that a change of mindset may lead to new laws and agreements through which disputed works of art can be shared among countries. To echo Cézanne’s great-grandson, such partnerships allow two great museums to show a single masterpiece for the benefit and enjoyment of a greater audience.

• Sharon Hecker’s forthcoming book is titled From Cultural Patrimony to Cultural Matrimony: a New Way of Dealing with Disputed Art Objects (2019)