“Everybody was always complaining about how dirty and awful it was,” says Chris Stein, “but still, everybody hung out and had a good time.” A far cry from the New York that Sinatra extolled, the city as depicted in the photographer and Blondie co-founder Chris Stein’s new book of images from the 1970s and 80s, Point of View: Me, New York City, and the Punk Scene, is certainly rough around the edges. Some of the characters Stein has captured with his camera look as though they’ve popped out of a Lou Reed song—transvestites, bums, strip-club clients, street urchins—and the same, more or less, can be said of the many seedy locales that provide the backdrop to what can nonetheless be called a love letter to New York. “Growing up in the middle of all that is a part of my history,” he explains.

Stein attributes the somewhat delayed publication of these photographs, a follow-up to 2014’s Negative: Me, Blondie, and the Advent of Punk, to a recent surge of enthusiasm he has witnessed about this era in New York’s history. “There’s a lot of interest in the period now,” he explains. ‘A lot of young people are curious.” He adds, “I just wanted to give an atlas here of the period a little bit and see if I could convey that.”

In the preface to the book, Stein waxes nostalgic about a sort of paradise lost. Yet back when he took the photographs, his aim wasn’t to document the scene for posterity or to play the role of archivist, unlike the artist Duncan Hannah, who mentions having written his newly published diaries of his teenage years in 1970s New York in an attempt to “stop time”. Stein’s approach—if there was one—was impromptu. “I don’t know if I was thinking so much about time and place,” he says, adding, “I think everyone was very much in the moment then and didn’t think of [the photos] in the context of history or anything like that.”

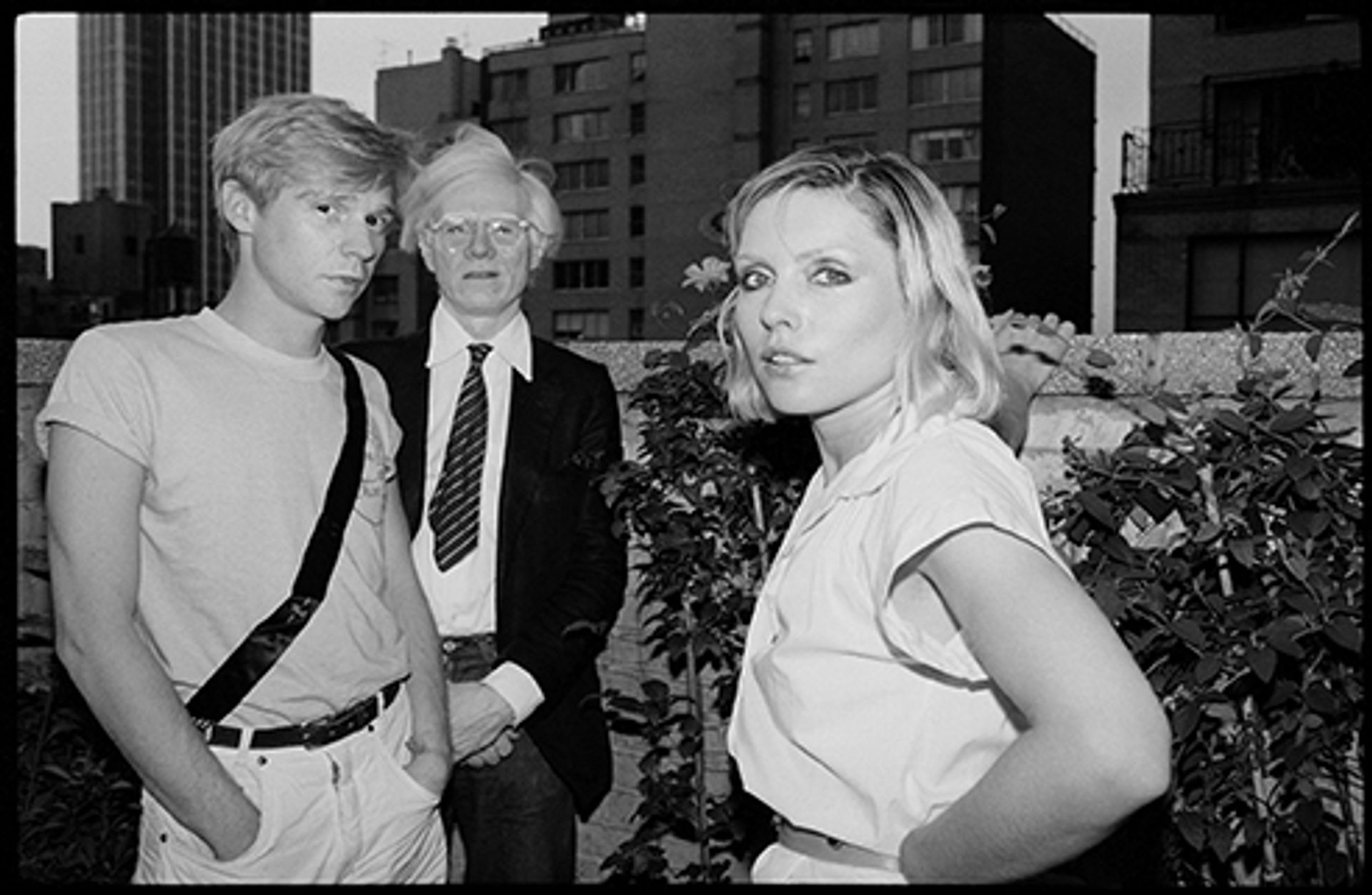

Rock icons like the Ramones, Iggy Pop and David Bowie as well as creators like Andy Warhol and William Burroughs make appearances throughout the book. Stein fondly remembers snapping the “really great” Iggy as well as Bowie—"very cautious” and “more controlling of his image”—but, as its title suggests, it is Debbie Harry, Stein’s bandmate and erstwhile lover, who is the book’s focal point.

He says he and Harry didn’t have a particular agenda despite leading one of the era’s most seminal groups. It was more about “just having fun”, he recalls. That is not to say that the couple was completely oblivious to the marketing side of things. He noted that one of his pictures of Harry ran in Creem magazine before the band's first record came out. “We were aware of the promotional aspect of it, but it was still always kind of like a party,” he says.

It’s difficult not to recall John Lennon’s words about places of sentimental importance in the song “In My Life”—“Some have gone and some remain”—while flipping through this book of mostly black-and-white photographs. Some, like Katz’s Delicatessen, still exist, while others, like the iconic club CBGB and Bill Graham’s Fillmore East concert venue, are no more–part of a vanished past that Stein now longs for. New York back then “was very fringe”, he says, adding, “There wasn’t a lot of money here.”

Toward the end of the book, Harry is seen atop the World Trade Center; a few pages later, plumes of smoke rise from where she stood. The jump from the 1980s to 9/11 is jarring. At the beginning of the book, Stein describes the New York of his childhood as well as the 70s and 80s as being more “magical”; 9/11 marked the beginning of the end of the magic for him, not just because of the devastation but because of the accelerated rise of commercialism he saw in its wake. “That was the big change moment, you know? There was a lot of money to be made with tourism and stuff,” he says. “Two years after 9/11, when the big rush of corporate interest started coming here—that was it.”

From left, Dennis Christopher, Andy Warhol and Debbie Harry in Manhattan Photo: © Chris Stein; © Point of View: Me, New York City, and the Punk Scene by Chris Stein, Rizzoli 2018