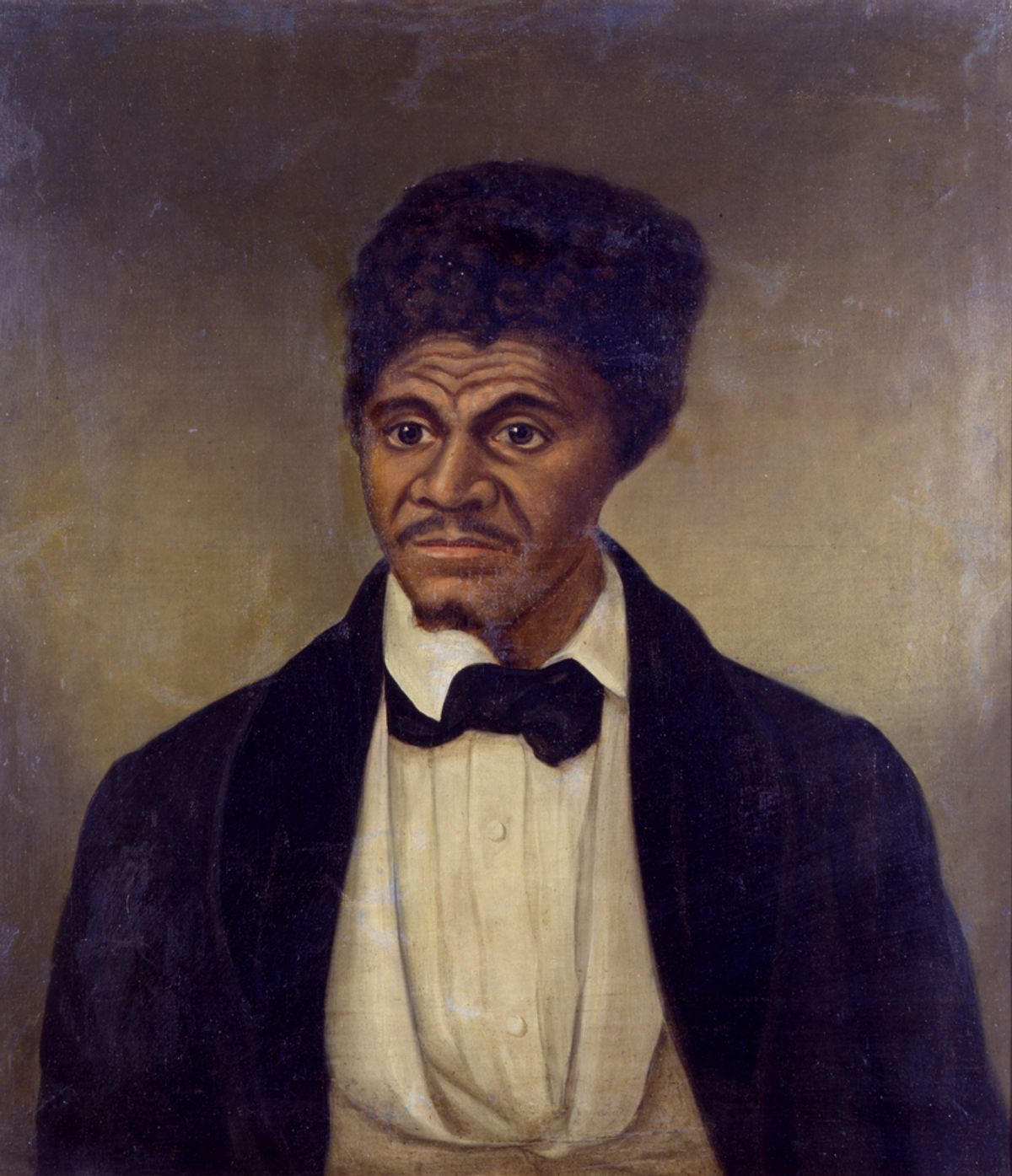

“I think most Americans today don’t really realise what a landmark decision the 14th Amendment was,” Louise Mirrer, the president and chief executive of the New-York Historical Society, said ahead of the opening of the museum’s show Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow (until 3 March 2019). That might have changed this week, as President Trump says he is seeking to end the birthright citizenship afforded by the amendment, which turned 150 this year and recognises all US-born or naturalised individuals as citizens. The show looks at the struggle for equality and full citizenship for African Americans in the period stretching from the end of the Civil War to the end of the First World War. Art, artefacts and archival materials in the exhibition include a portrait of Dred Scott (1857), the enslaved Missouri man who lost his lawsuit for freedom when the Supreme Court ruled that African Americans—whether enslaved or free—could not be citizens, and the journalist and activist Ida B. Wells’s Southern Horrors pamphlet (1892) reporting on hundreds of lynchings.

Gentrification, extreme wealth and even the art world itself are alluded to in the photographer Catherine Opie’s solo exhibition, The Modernist (until 12 January 2019), at Lehmann Maupin. The Los Angeles artist presents a brand-new body of stoic black-and-white works and her first ever film, both of which follow fictional arson attempts on real luxurious mid-century homes that pepper the Los Angeles landscape, including the blue-chip behemoth Larry Gagosian’s real home. The film of over 850 photo frames shows the main character—a struggling queer artist played by Opie’s long-time friend and muse Pig Pen—not only striking matches and pouring gasoline over the architectural pet projects of the ultra-wealthy, but also collecting the resulting fake news headlines and images of the fires. Pig Pen uses these to complete their own personal project: a dystopic collage chronicling the radical and rogue destruction of structures that once represented the American dream of progress and equality, but are now only in reach of the one percent. The frantic work is presented in the gallery in pigment prints.

This weekend is the last chance to see The Un-Heroic Act: Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women’s Art in the US (until 3 November) at the Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The works, in multiple media, upend traditional representations of assault throughout art history in scenes like the Rape of the Sabines. Some are abstract, such Sonya Kelliher-Combs’s brilliant work Guarded Secrets (2015), organic forms in sheep rawhide, and porcupine quills, which give a viscerally prickly and unsettling feeling. Others are representational, like Kathleen Gilje’s Susanna and the Elders, Restored (1998/2018), an X-ray image of underpainting of her own copy of Artemisia Gentileschi’s 1610 painting of the Biblical story—which Gentileschi made around the time she was raped by the artist Agostino Tassi—showing a more harrowing, violent scene. Look out for Senga Nengudi’s R.S.V.P. Revisited — Underwire (1977/2004), another visceral, abstract work with stuffed pantyhose in all different skin tones, which look like breasts of women, caught in metal springs (and pre-date Sarah Lucas’s pantyhose works by decades).