Were witches really “the Devil’s instrument”, or victims of a misogynist society? The art historian and self-described “criminartist” Christos Markogiannakis questions this and many other artistic interpretations of some of history’s most violent figures and events in a new book, The Orsay Murder Club. The pocket-sized edition, a follow up to his National Prize-winning The Louvre Murder Club, takes works from the Paris museum’s collection and analyses the crimes depicted using modern psychology and research. Below is an excerpt on the “Women Criminals, Witches, Gendercide, Femicide” based on Paul Ranson’s La sorcière au chat noir (Witch and black cat) (1893).

Until recently, women who kill were considered an unnatural phenomenon. From biblical whores, mythological heroines and over-masculine genetic abominations, to femmes-fatales, monsters, poisoners and witches, female murderers were either elevated to mythical status or reduced to stereotypes.

Even today, crimes committed by women are often seen not only as an offence against the victim(s) and society, but also against their own gender and perceived role. In contrast to their male counterparts, women who kill are often typecast as either: mad, and therefore to be pitied and not blamed; sad, and therefore compelled by external pressure or a need for revenge; or just bad, to be set aside from other women.

Female criminality fascinates mainstream media and is in the center of theoretical and empirical debates in contemporary academic, sociological, criminological and psychological circles. While there is still a long way to go in fully understanding and addressing female criminality, we have by now dispensed—in Western societies, at least—with the notion of women as the embodiment of evil. This perception of women as tools of the devil underpinned the “crime” of witchcraft, which brought hundreds of thousands of women to trial and torture and resulted in the execution of tens of thousands in Europe alone, when witch-hunts peaked between 1450 and 1650.

Yet up until the 13th century, people with “special powers” were tolerated, even venerated. Women who had mastered the use of herbs or natural forces to heal, provide pain relief or facilitate births, were often called upon.

By the early Renaissance, however, the folkloric perception of witchcraft and its potential dangers, rooted in an uneducated rural population, gained traction among the more cultured classes. Christian doctrine recognized the existence of witchcraft as an expression of the devil’s influence and classified it as heresy. Consequently, tolerance was eclipsed by persecution and punishment for those perceived as Satan’s servants. The publication of Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer Against Evildoers) in 1487 outlined a detailed legal and theological process, defined inquisitorial techniques to extract evidence, and established punishments with a single goal in mind: the extermination of witches. In their deranged misogyny, the Malleus authors state: “All wickedness is but little compared to the wickedness of a woman.” Widely published and circulated thanks to the re-cent invention of printing, it became a runaway bestseller, second only to the Bible for 200 years. It also became the main tool in the hands of secular judges—always men—to try, torture, humiliate and often execute thousands of illiterate women.

Witch-hunts and trials conducted by both secular and ecclesiastical authorities began to appear on a large scale in the 15th and early 16th centuries, and peaked in the 17th century. From France and Switzerland the persecution spread to Germany, where it reached its apogee, and then to Northern Europe and North America.

European witch-hunts gradually came to an end in the 18th century, but the figure of the witch remained popular in art and literature. It also found its way into late 19th-century symbolist painting.

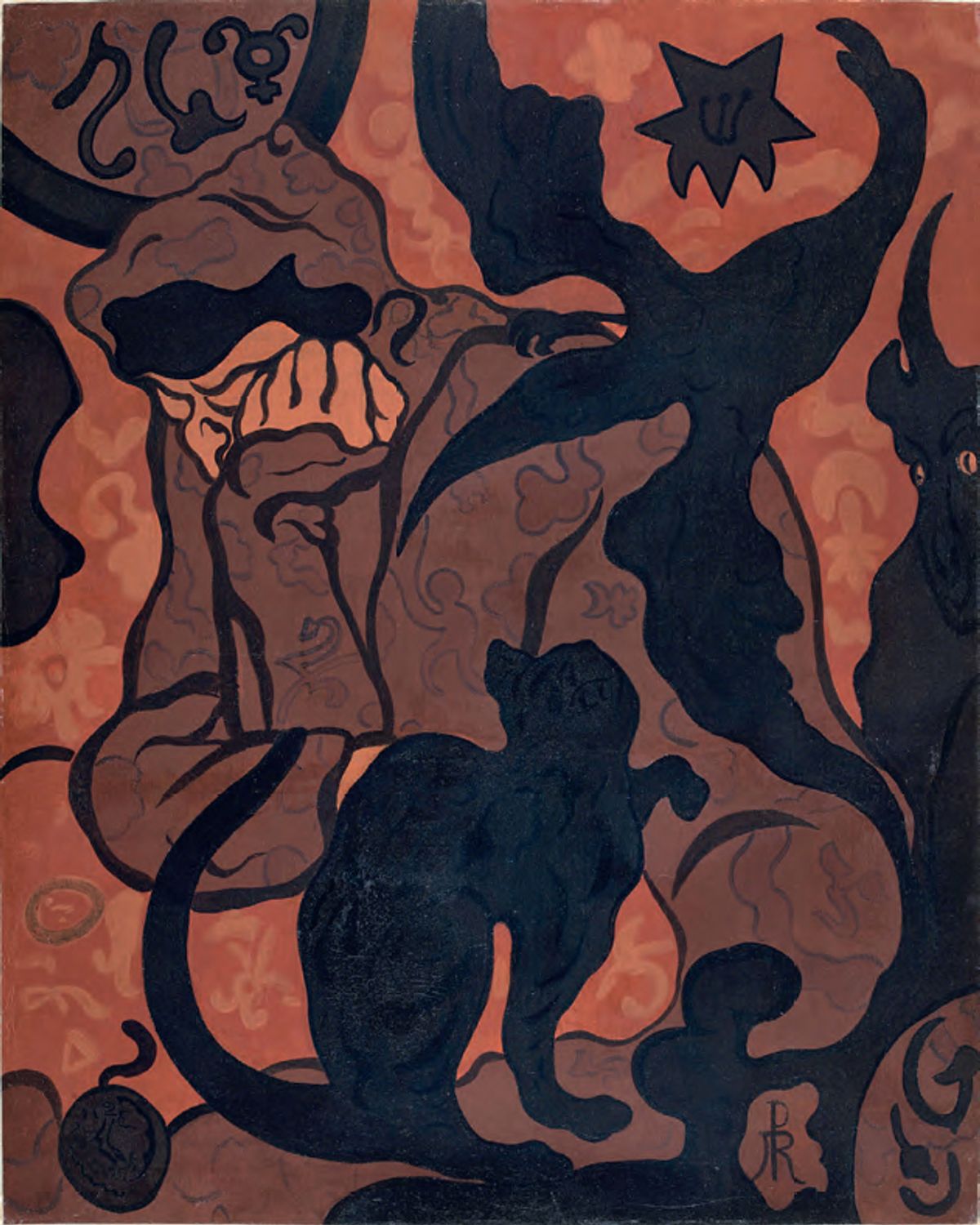

Paul Ranson’s witch occupies almost the entire composition of his painting. We see her slumped, her head supported by her arm. Her hand obscures part of her face, revealing only her eyebrows, her closed eyes and deformed, hooked nose. Her black hair is covered by the hood of her dress, which is ornamented by various motifs. She is surrounded by shadowy figures, objects and symbols. We see a witch ball on the lower left corner, an instrument that, according to folk tradition, provides protection from evil spirits. A black cat, that indispensable companion of black magic, sights a raven resting on the witch’s shoulder. In the background, the devil has his eyes fixed upon the cat and its master.

The raven’s neck and wing frame a pentacle (an emblem of Satanic worship) fused with a crescent moon containing the Hebrew letter Shin. On the left, just above the witch’s head, we see the astrological symbol of Mercury, a sign of intelligence, dexterity and elusiveness. Yet Mercury’s symbol is formed out of the biological sign of the female sex (♀) crowned with horns. It serves as a direct reference to the woman before us, a servant of Satan. The cabalistic symbols and Hebrew letters completing this highly decorative ensemble do not have a specific or even apocryphal meaning; they do not create a phrase or some kind of spell; but rather call to mind an imaginary landscape.

Since the 18th century, witches have often been depicted with an explosive and brutal vitality, a savage and unrestrained freedom. By contrast, Paul Ranson’s painting, despite its vivid orange color, is melancholic. The witch seems absorbed in her thoughts, just as this painting seems to be absorbed by its calligraphy and occult symbols.

There are two possible explanations for the main figure’s somber demeanor. She may be lost in her dark designs, preparing for action as her powers take form, surrounding her like opium smoke. Or she may herself be a victim to the Devil’s devices, which could explain her apparent sadness. Assaulted by the visions and nightmares surrounding her, she curls into herself.

Whatever the reason, its ambiguity as to her status—as a perpetrator or a victim—adds to the painting’s intrigue. It is Paul Ranson’s most symbolic and mysterious work, among a catalogue of esoteric paintings. The supernatural light emanating from within, the technique, expressive lines, surreal colors and decorative supremacy, all manifest its creator’s “perverse and complicated soul.” The painting’s exceptional modernity makes it realistic while also creating a hallucinogenic, almost psychedelic effect—somewhere between watching a shadow play and a piece of stained glass. This particular witch is said to have inspired Walt Disney in creating the Wicked Witch character for his classic 1937 film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs…

• The Orsay Murder Club, by Christos Markogiannakis, 236pp