In the opening pages of the expertly edited guide to the 57th Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, which opened on Saturday, the curator Ingrid Schaffner makes a startling admission: that there is no real theme to this year’s presentation. “The aim of this International is simply to inspire museum joy,” she writes. “Simply put: the pleasure of museums comes from the commotion of being with art and other people actively engaged in the creative work of interpretation. Draw on what you know.”

This is a refreshing place to begin. Too often, biennial curators try to cram a diverse group of artists and works of art into forced themes that shed little light, even for those with prior knowledge. But for those without an art background, there is the bigger sin of obscurantism, as if art is only for the cultured few. Schaffner, who has organised more than 30 artists and collectives into this year’s show, is eager to avoid that. She would rather that audiences from many backgrounds relate to what they know and take their own imaginative journeys.

This works especially well in one of the first galleries, which includes an ingenious and—by early, informal measures—wildly popular work by Lenka Clayton and Jon Rubin. Their installation begins with some history: between 1896, when the first International opened, and 1931, the Carnegie Museum of Art made open calls for submission by artists for each edition and rejected a total of 10,632 paintings. Records of the unwanted pictures, along with the artists and the dates they were painted, were kept and remain part of the museum’s archive.

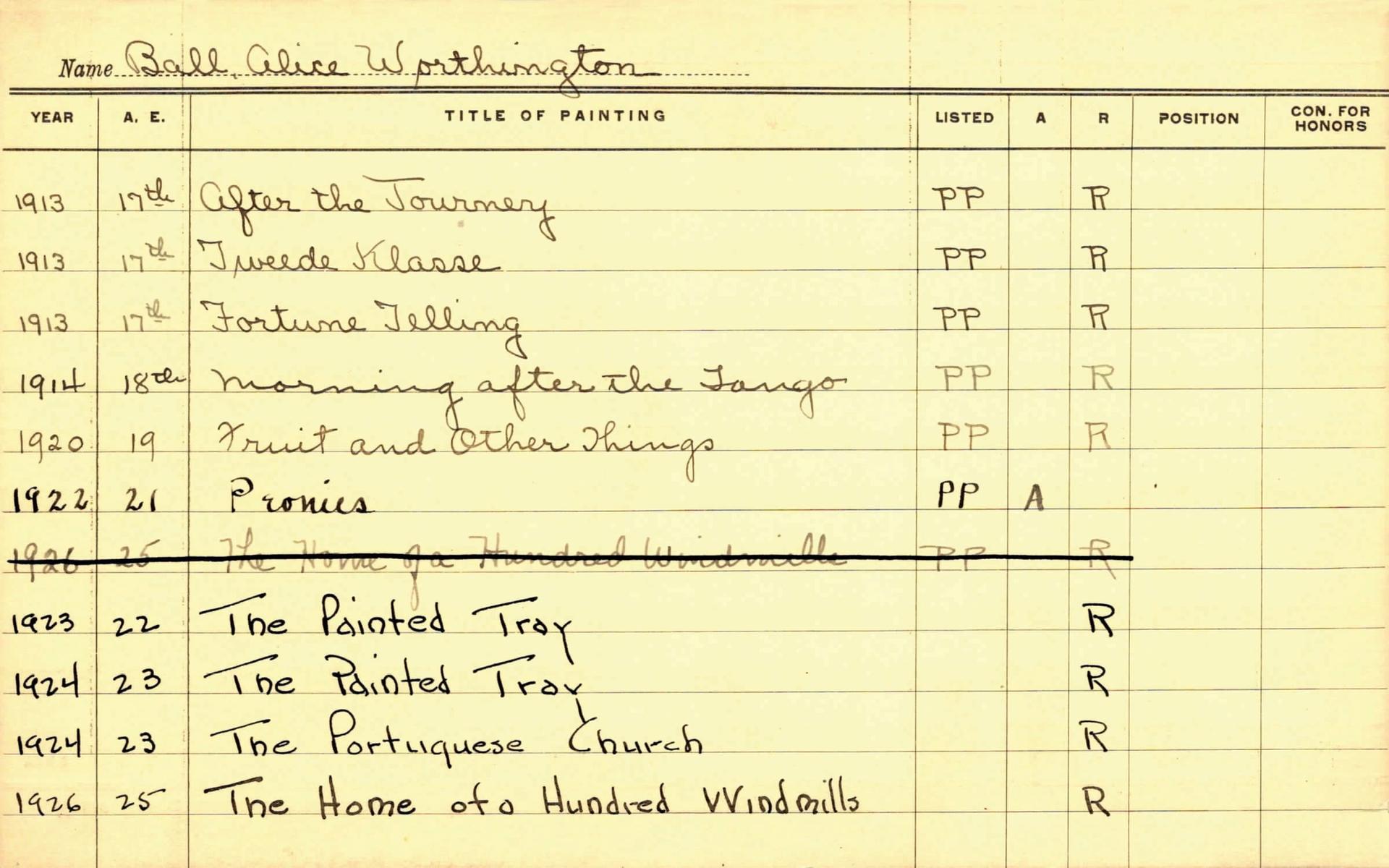

A Carnegie International Record Card from Lenka Clayton and Jon Rubin's project Courtesy of the Carnegie Museum of Art Archives

Clayton and Rubin have hired sign painters to sit in the museum and hand paint the titles of each rejected picture in alphabetical order. These works on paper are then displayed briefly in the galleries and handed out to visitors for free, along with documentation about the original artist and date. The brief titles—A Cowboy, High Tide on St Mark’s Square, Pittsburgh Flower Market—invite rich speculation. What do you think the painting No! I Am Not Pagliaccio may have looked like?

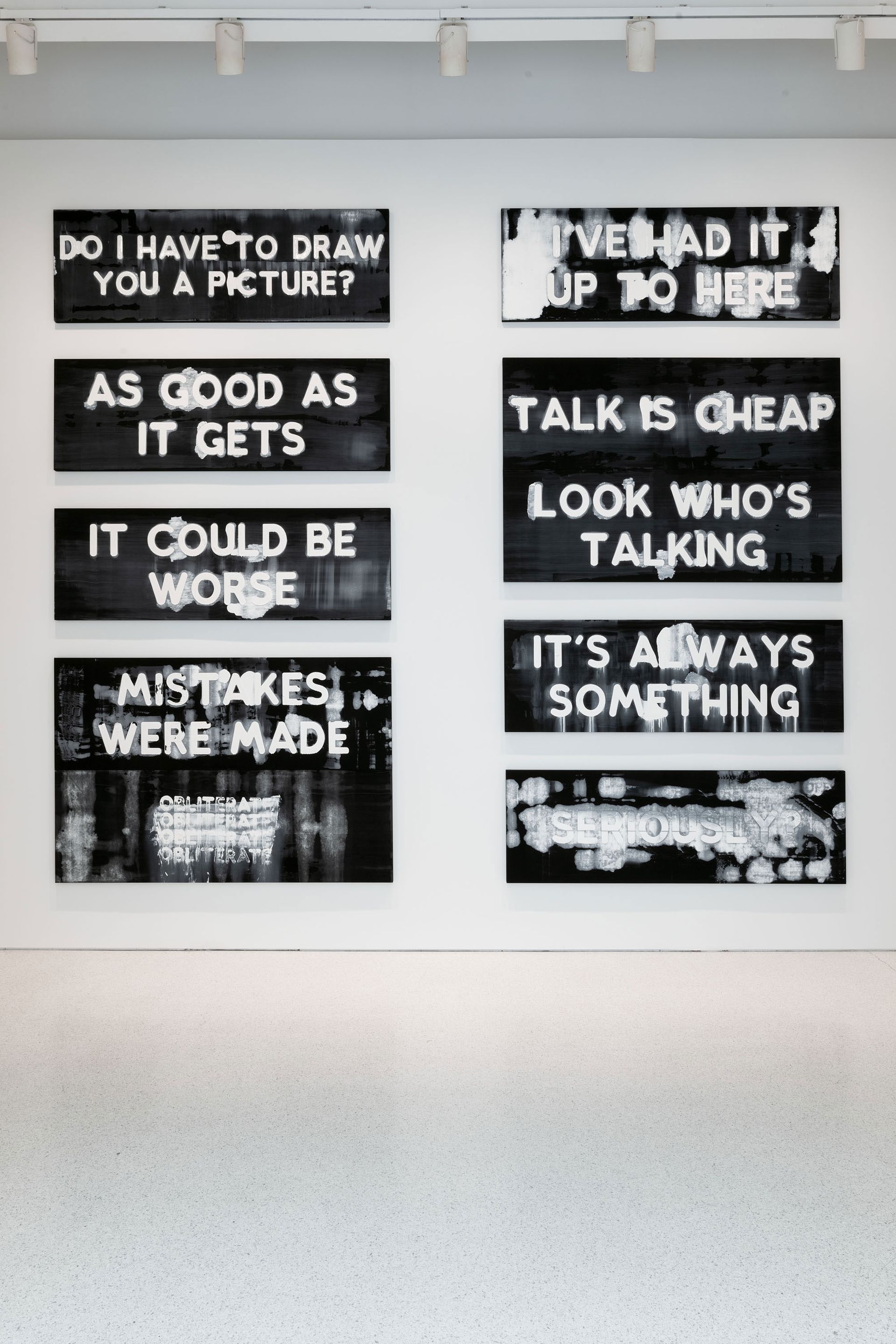

Nearby, a 70-foot-long comic strip by the Chicago artist Kerry James Marshall from his Rythm Mastr series, also attracts wide audiences, as does Jeremy Deller’s project just down the hall, in which he has installed tiny television screens into the museum’s permanent galleries of miniature period rooms. Alex da Corte’s work upstairs—a house built of neon lights with Halloween, Christmas, and Valentine’s Day decorations, inside of which there are videos featuring characters like Sylvester the Cat—also draws the public (and especially children). Then there is the resourceful directness of Mel Bochner’s text paintings, which are spread throughout the biennial. One of them simply asks: “Do I have to draw you a picture?”

Installation view of Mel Bochner's text painting at the 57th Carnegie International Photo: Bryan Conley. Courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc., New York/Paris

These examples naturally reach out to audiences beyond the tiny, rarefied art world; they do not need much curatorial guidance. This is the benefit of not forcing an interpretation, showing that some art can do its own work. Such is the case with Yuji Agematsu’s tiny sculptures made of everyday debris picked up on one of his daily walks. Three hundred and sixty-five of these “disgusting and exquisite” miniature works, as the guide aptly describes them, are arranged in rows and columns like a month-by-month calendar. Thaddeus Mosley’s totem-like wood sculptures are similarly clear of mind, and somehow seem to float despite their heft.

Yet Schaffner’s minimal curatorial touch also leaves much of the art in peril. When the work is not strong enough to stand on its own—which is the case more often than not in this show—it has little to fall back on. Schaffner seems to have recognised this, so she has sprinkled some of the Carnegie International throughout the museum’s permanent galleries so that the new art can enliven the old and vice versa.

This works to various degrees. When it fails, it looks like Zoe Leonard’s redundant and repetitive photographs of the Rio Grande, which encircle a balcony full of plaster casts of Greek and Roman statues. The mix-and-match strategy fully succeeds only once, with Saba Innab’s work, which is one of the best in the show. Her sculpture—an abstract ruin of concrete and steel that mimics a tunnel dug out by the embattled citizens of Gaza—sits not far from casts of Greco-Roman statues, which works as a succinct and jarring juxtaposition between East and West.

But there is a bigger issue with the exhibition, which is a nagging sense of attrition. The International works must be actively sought out and identified against the permanent collection, which can be difficult. Schaffner and her team have deliberately decided to eliminate all but the most essential wall labels, which is another tactic in service of allowing the art to speak for itself. (“Some labels aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on,” the guide boldly states.)

By walking from one part of the museum to another in search of art, it is easy to lose the thread of the exhibition—if a thread can be said to exist in such a loosely organised show. In the end, it seems most of those ties that bind are outside of the works of art on display. Importantly, Schaffner and her team have made the admirable and necessary decision to meet guidelines set out by the organisation Working Artists and the Greater Economy (Wage), ensuring that each artist in the show has been paid a minimal fee. Every museum exhibition, biennial or otherwise, should meet these standards or exceed them.

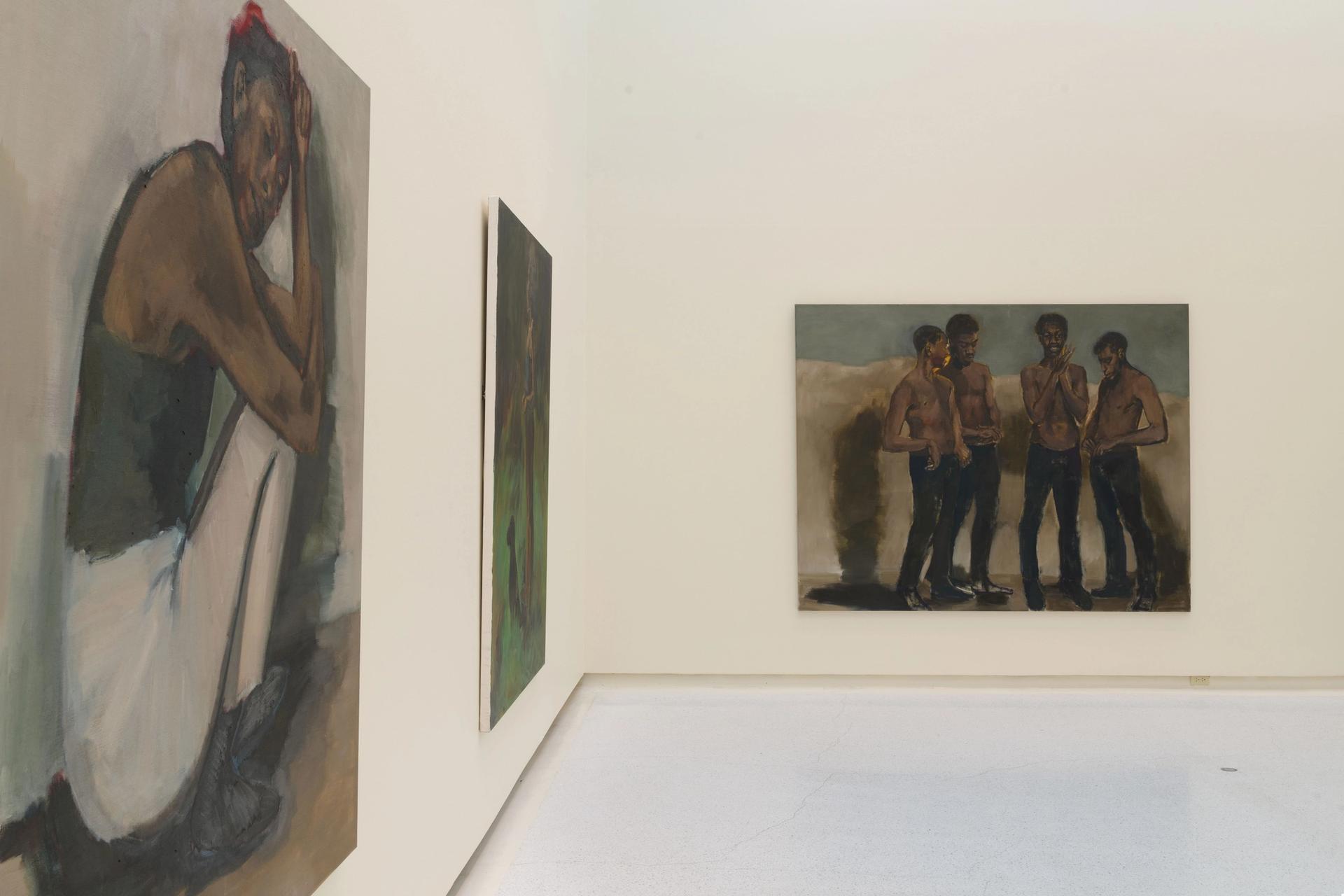

Installation view of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye's works at the 57th Carnegie International Photo: Bryan Conley. Courtesy the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Corvi-Mora, London

So the Carnegie International, as ever, is a work in progress. Schaffner says as much in the show’s lovely guide, which is geared towards a general audience (and even includes a guide to Pittsburgh). In an early section, after a brief survey of previous editions of the Carnegie International, she writes that the ongoing exhibition “is not a series of shows that supplant one another. It is an aggregate.”

It is perhaps not unlike the tremendous portrait paintings of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye on the show’s second floor, which are strategically full of small unpainted areas, perhaps stressing that identity and personhood is always undoing itself and developing. Such is the case with the biennial as an exhibition form. There is boldness here; it is brave to let the art speak directly to audiences with little interference. But sometimes, a guiding hand can help raise mediocre objects to a higher plateau.

• Carnegie International, 57th Edition, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, until 25 March 2019