In 1906, heeding the call of a spirit summoned in a séance, the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) broke with academic tradition and began creating a series of 193 boldly colourful paintings that bore scant resemblance to any visible reality. She completed them in 1915, and later wrote of her desire to see them reside in a circular temple, where visitors would ascend a spiralling contemplative path.

Now, the artist’s vision is being realised in an ambitious exhibition opening tomorrow (12 October) on the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s looping Frank Lloyd Wright-designed ramps. It both challenges and enriches the longstanding narrative of the museum’s beginnings, encouraging the thought that the so-called fathers of abstraction had a female counterpart who could lay claim to being an earlier pioneer.

Af Klint’s foray into non-representational work actually predates that of Wassily Kandinsky, a mainstay of the Guggenheim’s original collection, who is often credited with having invented abstract painting. And her immersion in spiritualism, science and an “invisible world” intriguingly parallels the thinking of Kandinsky, František Kupka and other practitioners of the “non-objective” painting movement championed by the museum’s co-founder, Hilla Rebay.

“The Modernists whom we call the pioneers of abstraction were making their strides six or seven years later than she was.”

“Her existence and her work bring all kinds of questions to the story we tell about early 20th-century abstraction, the way people worked, and different intellectual thoughts and theories that they were engaged in,” says the Guggenheim’s director of collections and senior curator, Tracey Bashkoff. “The Modernists whom we call the pioneers of abstraction were making their strides six or seven years later than she was.”

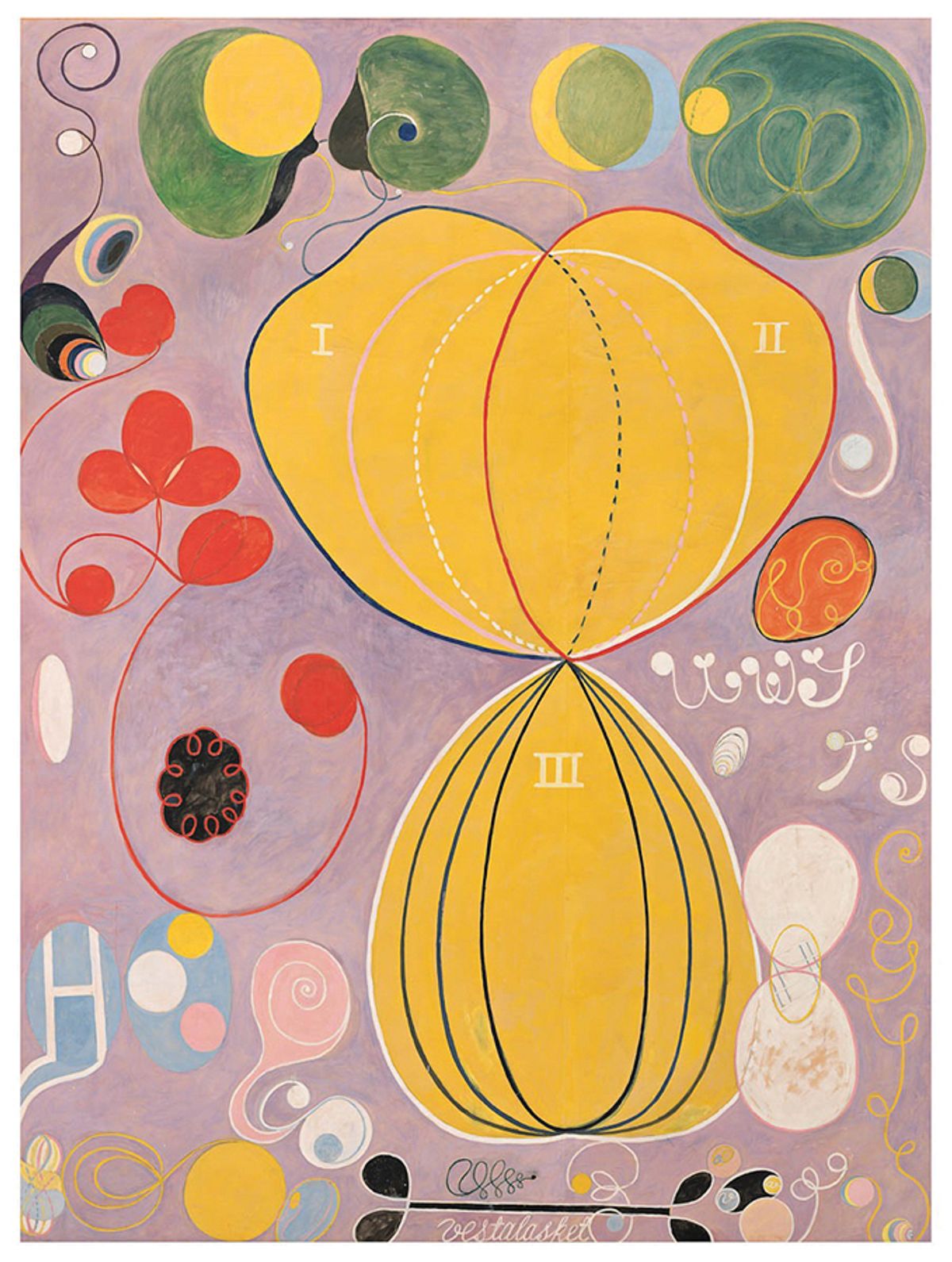

Showcasing the breakthrough years 1906-20, the Guggenheim’s exhibition delves into Af Klint’s relationship to Modernism and her interest in theosophy, spirituality, the natural sciences and atomic particles. A trained painter, she and four other women met to practise automatic drawing and writing at the behest of spirits they channelled in séances. In 1906, Af Klint reported that the spirits had commanded her to create a cycle of works. Thus began the series Paintings of the Temple, in which she invented an abstract vocabulary blending biomorphic and geometric forms.

A portrait of Hilma af Klint

“The spiritualist circles were certainly ones that allowed women to come to the fore, and respected women as intellectual forces in the propagating of ideas,” Bashkoff says. “So I think that it was a comfortable zone for her and a nurturing, supportive environment.”

Yet Bashkoff emphasises that Af Klint should not be regarded solely as an outsider, because other early Modernists had similar preoccupations. Drawing on new biographical research, the exhibition aims to dispel “the idea that she was reclusive, cut off by location and language, and engaged in only esoteric and eccentric pursuits”, Bashkoff says. “Séances—it sounds very fringe to us today but it had a more central role for artists and intellectuals at the time.”

The show is supported in part by the LLWW Foundation, the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, the Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation, the Robert Lehman Foundation and the American-Scandinavian Foundation.

• Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 12 October-3 February 2019