Sketches of a Caribbean kitten were reused by Paul Gauguin in a painting which he made while he was living with Vincent van Gogh in Arles. The drawings—one of which has just gone on show in Amsterdam in the Van Gogh Museum’s exhibition on Gauguin and Laval in Martinique (until 13 January 2019)—are from a sketchbook used by Gauguin on the island in the summer of 1887.

When Gauguin later stayed with Van Gogh in the Yellow House, in 1888, he brought with him the sketchbook, which includes several drawings of a kitten, in slightly different positions. The pet probably belonged to a neighbour in the settlement where Gauguin and his artist friend Charles Laval lodged just outside the Martinique town of Saint-Pierre.

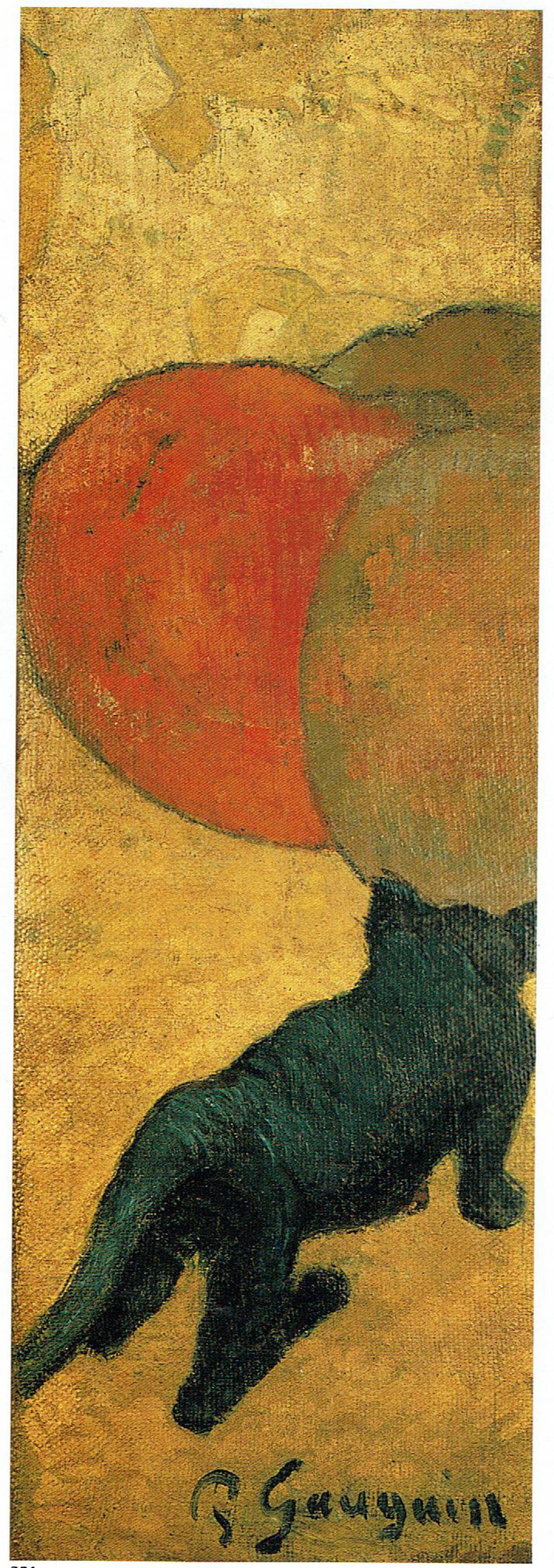

Paul Gauguin, Drinking Kitten, 1887, private collection

One of the sketchbook pages, which does not seem to have been exhibited before, shows a kitten drinking from a bowl. Gauguin also used the kitten as a detail in a Martinique painting, Tropical Conversation (belonging to a private collection, it could not be borrowed for the show) and much later in his 1897 masterpiece, now at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

When Gauguin came to Arles in October 1888, bringing his sketchbooks, he and Van Gogh had long discussions into the night about painting, talking about the Martinique experience and the future of modern art. Vincent and his brother Theo had also recently acquired two of Gauguin’s Martinique paintings and a drawing, which had remained in Paris.

Vincent wrote to Theo soon after his friend’s arrival: “What Gauguin has to say about the tropics seems wonderful to me. There, certainly, is the future of a great renaissance of painting.” Van Gogh and Gauguin both developed an enthusiasm to establish “a studio of the tropics”.

Martinique

The Van Gogh Museum’s show is the first exhibition to focus on Gauguin’s visit to Martinique, where he stayed from June to October 1887. Reassembling the oeuvre proved a challenge, but their curators succeeded in borrowing nine of the 17 paintings (the remainder, in private collections, eluded them).

Equally important, the museum is showing 18 sheets (many double sided) from the three sketchbooks which Gauguin used in Martinique. These were disbound in around 1930 and are now widely dispersed.

Tate watercolour

Research for the exhibition has added another work to Gauguin’s oeuvre. Tate owns a double-sided work on paper which was bequeathed by the Earl of Sandwich in 1962. One side shows a watercolour of a tree and the reverse has a sketch of a man, which Tate curators considered might represent Gauguin.

The earl had had purchased the sheet in 1931 from the sale of Paco Durrio, a Spanish sculptor who was a friend of Gauguin. Despite this excellent provenance, Tate downgraded it soon after the acquisition to Circle of Gauguin. It was not displayed or even reproduced in the catalogue of the Gauguin exhibition held at Tate Modern in 2010-11.

After a detailed examination at the Van Gogh Museum—assisted by the Wildenstein Plattner Institute and Art Institute of Chicago specialists—it is now being exhibited as a work by Gauguin, and side by side with the other sketchbook pages this seems the correct judgement. The portrait drawing does not have the facial features of Gauguin, and it is now said to depict Laval. “We welcome this exciting research and we will be reconsidering the attribution of the work accordingly,” a spokesman says.

Romance

The exhibition also focuses on Laval, who remained on Martinique after Gauguin’s departure and then returned to France in the first half of 1888. The curators, Maite van Dijk and Joost van der Hoeven (of the Van Gogh Museum), conclude that both artists created compositions by combining motifs and working from their imagination: “Their stay on Martinique paved the way for the more subjective and radical works they would make in the following years.”

Gauguin and Laval were close friends while they were in Martinique, but ended up bitter rivals. Both were attracted to the 19-year-old sister of their artist friend Emile Bernard, Madeleine. Gauguin, a notorious womaniser, failed to win her affection, and when Laval succeeded, he dismissed Laval as an “imbecile”.

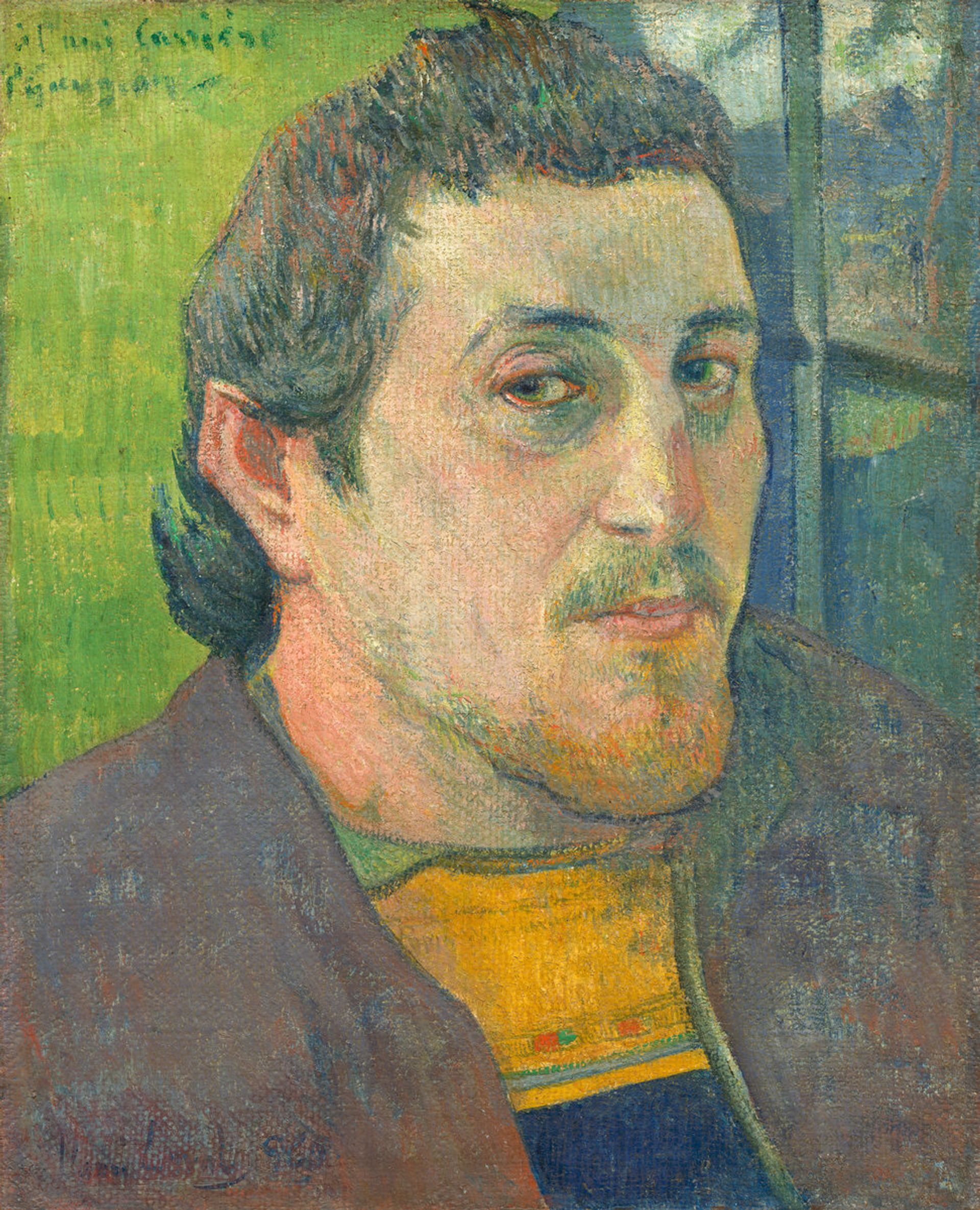

Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait for Carrière, 1888-89, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Gauguin took his revenge. He had painted a self-portrait, portraying himself beside a window with a view outside of a Martinique landscape. Gauguin gave it to Laval, with a dedication. After the row over Madeleine, Laval angrily returned the painting. Gauguin then removed most of the original dedication, adding a new one for another artist friend, Eugène Carrière. This self-portrait, now owned by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, is in the Amsterdam exhibition.

In April 1890 Marguerite and Laval became engaged, although they split up after Bernard’s family realised that Laval lacked the financial resources to look after the young woman. Laval died of tuberculosis in 1894, aged just 33. He had not yet achieved fame, and his surviving work is now very rare. Seeing his oeuvre in the excellent Amsterdam show makes one realise that he was a talented artist—and he deserves more attention than just being regarded as Gauguin’s companion.

- Gauguin and Laval in Martinique, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, until 13 January 2019