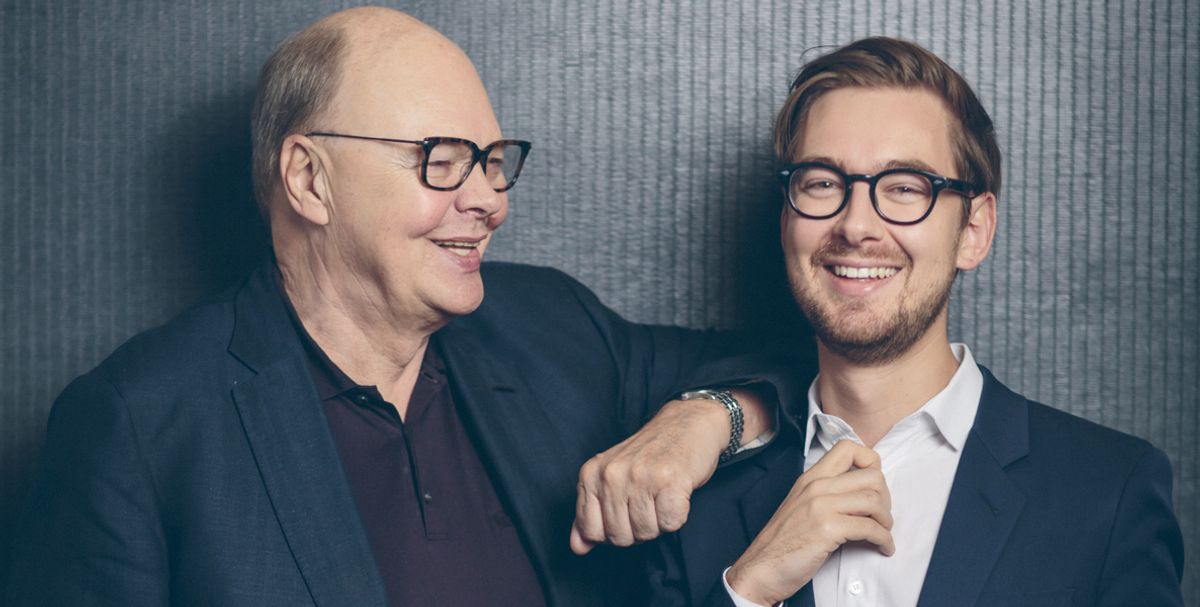

“It’s easy to connect to a young artist when you’re both in your 20s and share a language. It gets harder when you’re in your 40s and 50s. But the defining quality of a gallery is to be able to keep connecting.” So summarises David Zwirner, the son of a respected art dealer, Rudolph Zwirner, and arguably the most successful primary-market dealer of this generation, who now has two of his own children among the gallery’s international staff of around 200 people.

He is a rarity. A cursory look at the recent history of art dealing shows that the gallery gene does not normally survive beyond one generation—generally that golden period when founder and artists are in their youthful prime. New York’s dealing pioneers from the 1950s, such as Sidney Janis and Leo Castelli, are just some of the industry-revered galleries whose primary market prowess essentially died with their founders.

Has much changed since then? “It’s still very, very difficult. Once upon a time, the idea of a contemporary gallery outliving its founder was really not a possibility. That still holds true today,” says Marc Glimcher, the president and chief executive of Pace Gallery, who began there in 1985, following in the footsteps of his father, Arne Glimcher. Marc Glimcher acknowledges there have been growing pains along the way, for him and for the gallery, but says his 2005 Logical Conclusions exhibition in New York—an ambitious group show, which included several museum loans—marked a real turning point. “It was my Grids,” Glimcher says, referring to a landmark 1979 exhibition organised by his father.

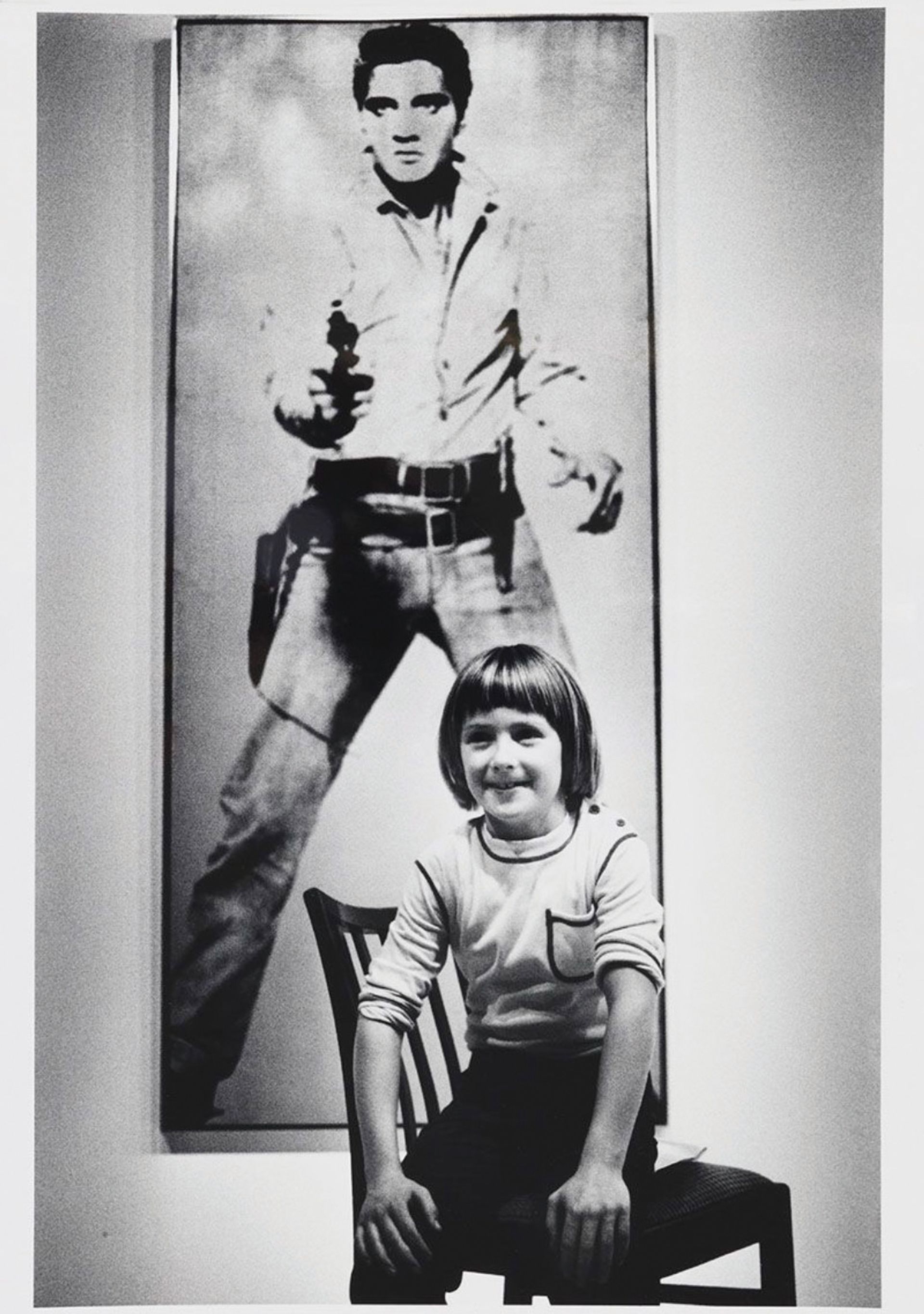

A young David Zwirner Courtesy of David Zwirner

Glimcher’s gallery is now among a handful that seem to be finding a formula for next generation success, while the future of others appears far more fragile. Then there are the unknowns. Market players speculate about the future business plans at Marian Goodman, Gladstone Gallery, Paula Cooper and, of course, the Gagosian empire—all businesses led by founders now in their 70s and 80s.

Certainly, the backdrop has changed. The top end of the art market has become a major international industry, which Glimcher argues gives its businesses more potential longevity. “The cult of the personality has shifted, and galleries have become institutions,” he says. “In a way, my father foresaw that,” he adds, noting that Arne, who founded Pace in 1960, did not name the gallery after himself—‘Pace’ sounds like a neutral brand, though it is in fact the anglicised Yiddish name of his grandfather. “I don’t have founder’s pride, I don’t need it all to be mine. It’s not about one person, it’s about building a team,” Glimcher says. Lisson, another gallery that seems poised for well beyond its 50 years of operation, carries the name of a place, not a person.

The art adviser Emily Tsingou notes a related dynamic. “These days, if you want to be with the big boys, you have to be in more than one location,” she says. This gives would-be successors a new opportunity to cut their teeth, away from the watchful eye and potentially too-weighty reputation of a gallery founder. Zwirner—who opened a new gallery rather than taking on his father’s business—says that, by opening in New York instead of in Germany, where Rudolf Zwirner had operated, he was better able to “spread his wings”.

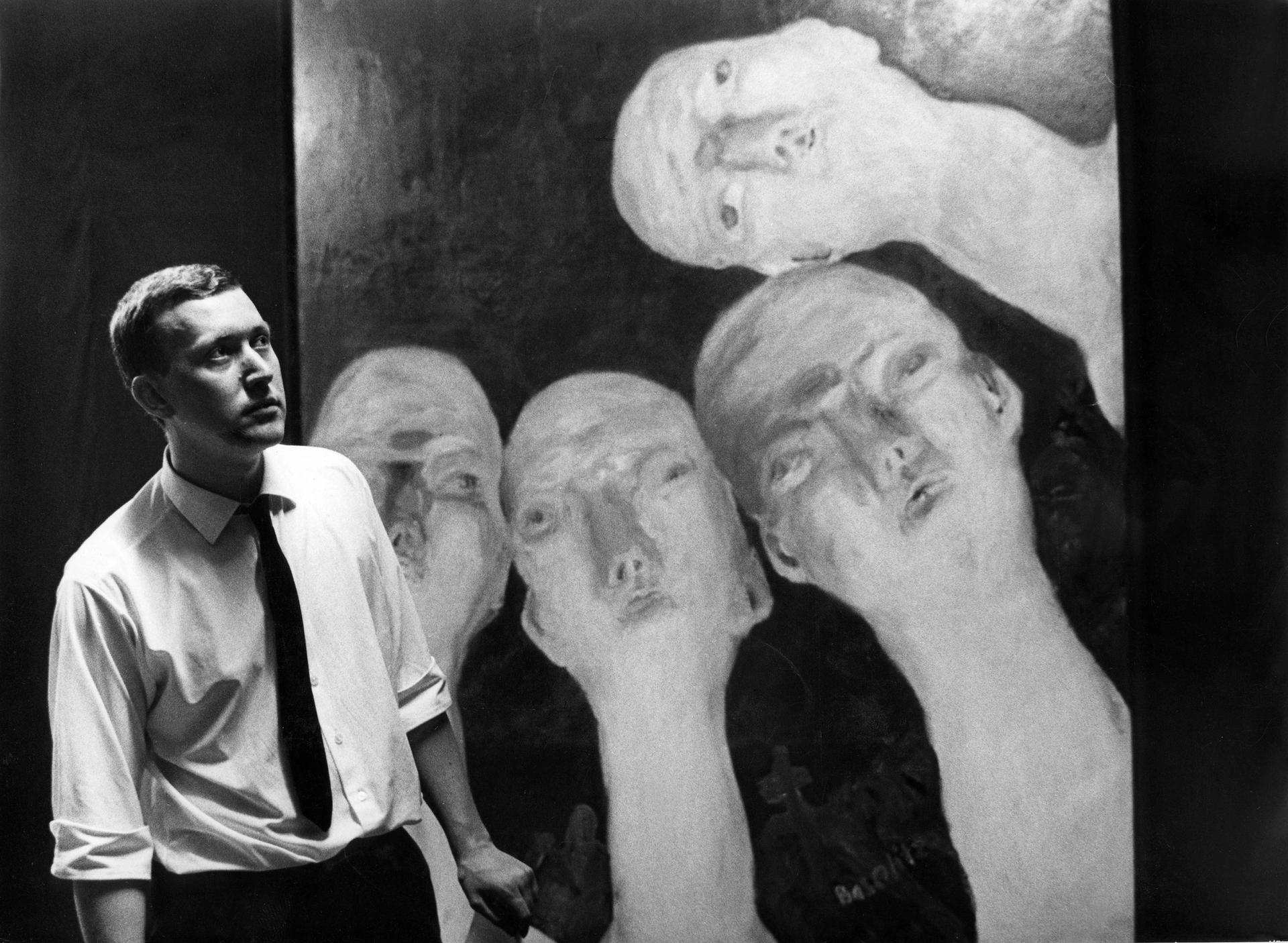

The German gallerist Michael Werner in 1964 © Czechatz/ullstein bild, Getty Images

The spirit continues. At the end of September, Max Hetzler’s son, Max Edouard, opened the Berlin- and Paris-based gallery’s London space, joining forces with Sarah Horner, previously at Skarstedt Gallery. Before that, at Lisson Gallery, Alex Logsdail, the son of its founder Nicholas Logsdail, joined the gallery officially in 2009 and took the British business to New York in 2016, something that he says was an important part of making his own way. “It’s challenging. You don’t get instant respect and validation—if anything, there is a higher level of scepticism and charges of nepotism are guaranteed. You have to rise above it and do something uniquely your own. If you try to replicate what has already been done, you are guaranteed to fail,” Alex Logsdail says. He adds: “The worst possible scenario would be to say: ‘I have to check with my dad’.”

Some founders and more senior directors are rather relieved to hand over the reins to a younger generation willing to go to every art fair or to oversee a social media marketing campaign. “We travel all over the world, all these fairs, the system is bigger than we are,” says Gordon VeneKlasen, a partner at Michael Werner gallery. For his gallery, survival has meant making many changes. VeneKlasen joined as a partner in 1990 and opened the German gallery’s space in New York and, in 2012, in London.

The business operates only in a small way in Berlin now (through Werner’s home rather than a gallery) and some of its core post-war artists, including Sigmar Polke, A.R. Penck and, most recently, Per Kirkeby, have died—and there is no guarantee that an artist’s estate will always stick with its original gallery.

Finding “new blood” is important, VeneKlasen says: “When we started working with Peter Doig, he was a young artist; now he’s turning 60.” The gallery is increasingly working with artists who it does not officially represent to tap into new audiences, such as Florian Krewer and Raphaela Simon. They were both students of Doig in Düsseldorf who have had recent shows in New York’s Chinatown through Michael Werner’s collaboration with Tramps gallery. Other galleries test the waters in a similar way—last month Alex Logsdail opened a show by the Texas-born artist Hugh Hayden at Lisson’s 10th Avenue space in New York (Border States, until 27 October).

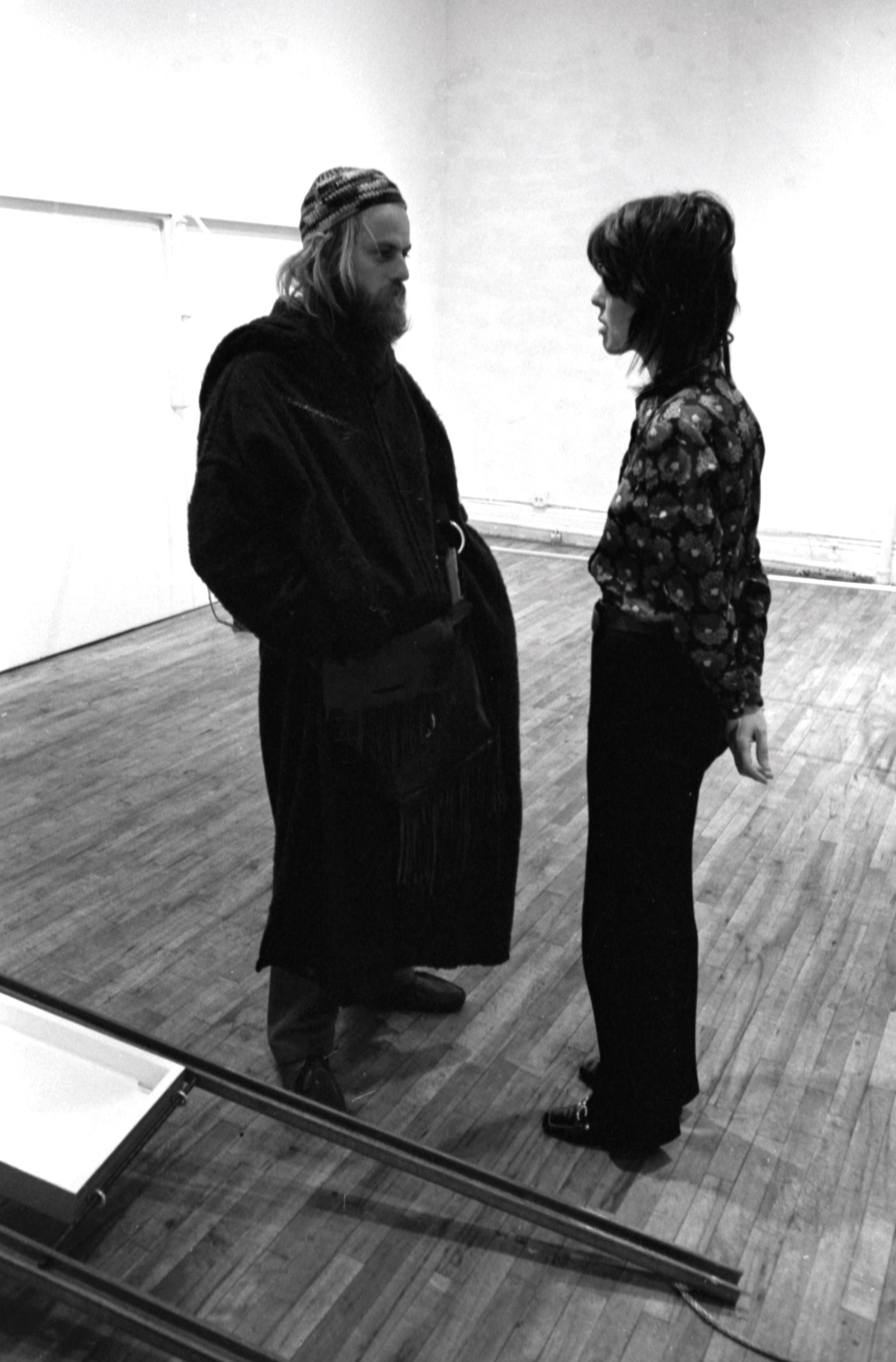

Paula Cooper talks to a visitor in her New York gallery in 1971 © Fred W. McDarrah, Getty Images

Michael Werner is 79 but, VeneKlasen stresses, “I’m hoping he has another 20 years in him.” He acknowledges that the relentless pace of running a gallery in the 21st-century can take its toll, however. “We don’t have 20 directors and 50 artists; I sometimes wish we did,” VeneKlasen says.

In June, the New York dealers John Cheim and Howard Read announced the closure of their public facing gallery, Cheim & Read, after more than 21 years, and partner Adam Sheffer moved to Pace. At the time Read said “there is a global, corporate gallery model [of] 60-plus artists… This was never our interest or goal.”

Tsingou thinks ultimately size does not matter: “The galleries that survive are those who recognise the importance of connoisseurship and of having close relationships to museums,” she says. But she acknowledges that this is something of a luxurious position. “Of course, museums can take three months to pay, so you need to have structured your business accordingly.” Certainly, any gallery that finds a way to survive out there in a world where liquidity is lumpy, bank loans are tricky and the value of your stock is variable deserves to keep going.

And if it works, keeping it in the family also has some advantages. Zwirner says that his children grew up knowing artists such as Luc Tuymans and Raymond Pettibon and that his senior staff, many of whom have been working with him for more than 20 years, also know his family well. However, he is not committing to them taking the reins. “I’m 53, I’ve hopefully got a few years to go, and art dealers don’t seem to retire,” he says, though he adds that the fact that his kids “love the business and want to run it is incredibly exciting for me”.

Both Zwirner and his younger counterparts stress the importance of not resting on any laurels. Logsdail says: “Irrespective of taste, time or trends, you have to keep building your programme; any gallery wholly satisfied with its group of artists is in decline or beginning a decline.” Zwirner concludes: “Losing content is the kiss of death.”