For the second year running, female artists have their own special section at the heart of Frieze London. It is especially appropriate since 2018 marks the centenary of women’s suffrage in the UK. Social Work features solo presentations by eight women, across different generations, whose work challenged the male-dominated art world of the 1980s and 1990s. The subject matter may not be as eye-popping as the blatantly sexual imagery of last year’s special section Sex Work, but this time the pieces extend beyond the solely bodily to address wider social, political and personal issues.

The artists selected for Social Work were chosen by an all-female panel (which included myself) to show that while the mainstream art world was busy celebrating the paint-splattered machismo of Neo Expressionism (the New Spirit in Painting exhibition at London’s Royal Academy of Arts in 1981 did not include a single woman), female artists were working behind the scenes, and under the radar, to address a very different status quo. The pieces in Social Work show that the artists often achieved this using many different means and media.

There are, of course, paintings but there are also the soft sculptures and painted story quilts of Harlem-born Faith Ringgold, the films and videos of London-based artist Tina Keane, and wearable sculpture and exquisitely staged photographs of viscera by the late UK artist Helen Chadwick. The show includes collaged hand prints by the late US artist Nancy Spero, paintings as well as wooden and metal assemblages from Turkish-born Ipek Duben and the transparent photographs of Cape Town’s Berni Searle, who at 54 is the youngest artist in Social Work. In their form as well as their content, these women were using their art to push at the boundaries of accepted convention.

Ipek Duben’s Sherife, Istanbul (1981) Courtesy of the artist and Pi Artworks

looking beyond the female form

In some cases, the female form is conspicuous by its absence. Corpus (1984-85), by the US conceptualist Mary Kelly, is the first section of a larger installation entitled Interim (1984-89), which followed on from her seminal work Post-Partum Document (1973-79). Corpus brings together dramatically photographed images of garments and accessories—in this case a black leather jacket and a handbag—each accompanied by handwritten text on Plexiglas panels, which communicate the first person experiences, both physical and psychological, of women as they encounter middle age. “The question I wanted to raise is, what is a woman? What about the older woman?” Kelly says. “When I made the work, I was in my 40s and it’s about the kind of fantasies we have [related to] image and body. But I wanted to look elsewhere from images of women as we were saturated with all that. I wanted to hear a voice.”

Clothing also forms the subject of the Sherife series of paintings by Duben, who returned to her native Istanbul in the late 1970s after studying in New York and realised that “as an artist, I had to come to terms with my own personal and cultural roots and the whole question of family identity, sexual identity and religious identity.” The paintings take their name from Sherife, a cleaner from an Anatolian village who had been abandoned by her husband. “She would not agree to model for me, as for her it would constitute a sin,” Duben remembers. Duben chose to depict her clothes instead. “I painted the headless Sherife contained in a shapeless dress, which revealed nothing about her physical presence and represented her absence. At the time I felt I had painted an iconic Turkish woman.”

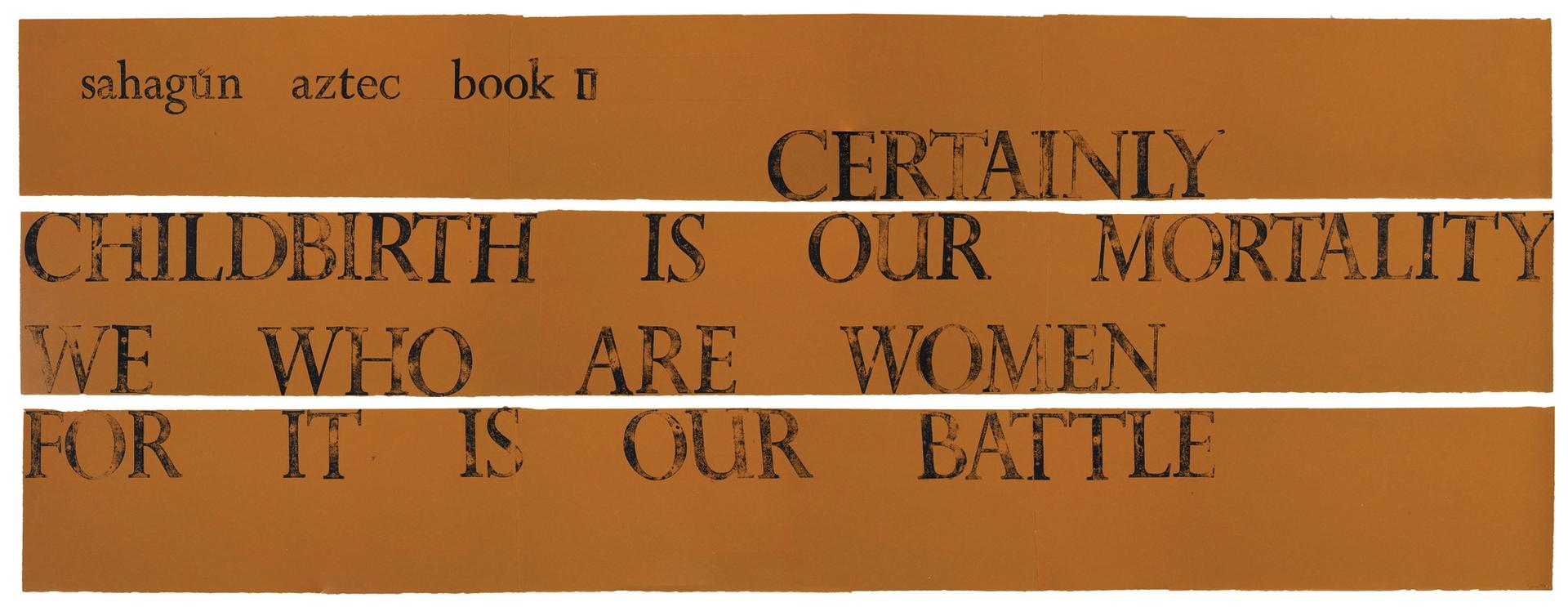

Duben echoes the view of all Social Work artists when she describes her practice as “political, social and psychological”. Here feminism is not restricted to gender politics, but challenges wider injustices and abuses in society, drawing on both the past and the present. Keane’s video In Our Hands, Greenham (1982-84) references a women’s group who established a peace camp at the Greenham Common airfield in Berkshire in 1981 in protest against the UK government’s decision to store nuclear weapons there; while Spero borrows archaic images of females from Ancient Greek, Aztec and Prehistoric sources to support her struggle for justice in 20th-century war zones in South Africa and El Salvador. “Certainly childbirth is our mortality/We who are women/For it is our battle”, states her text work Aztec Sahagun (1979), shown for the first time in Social Work.

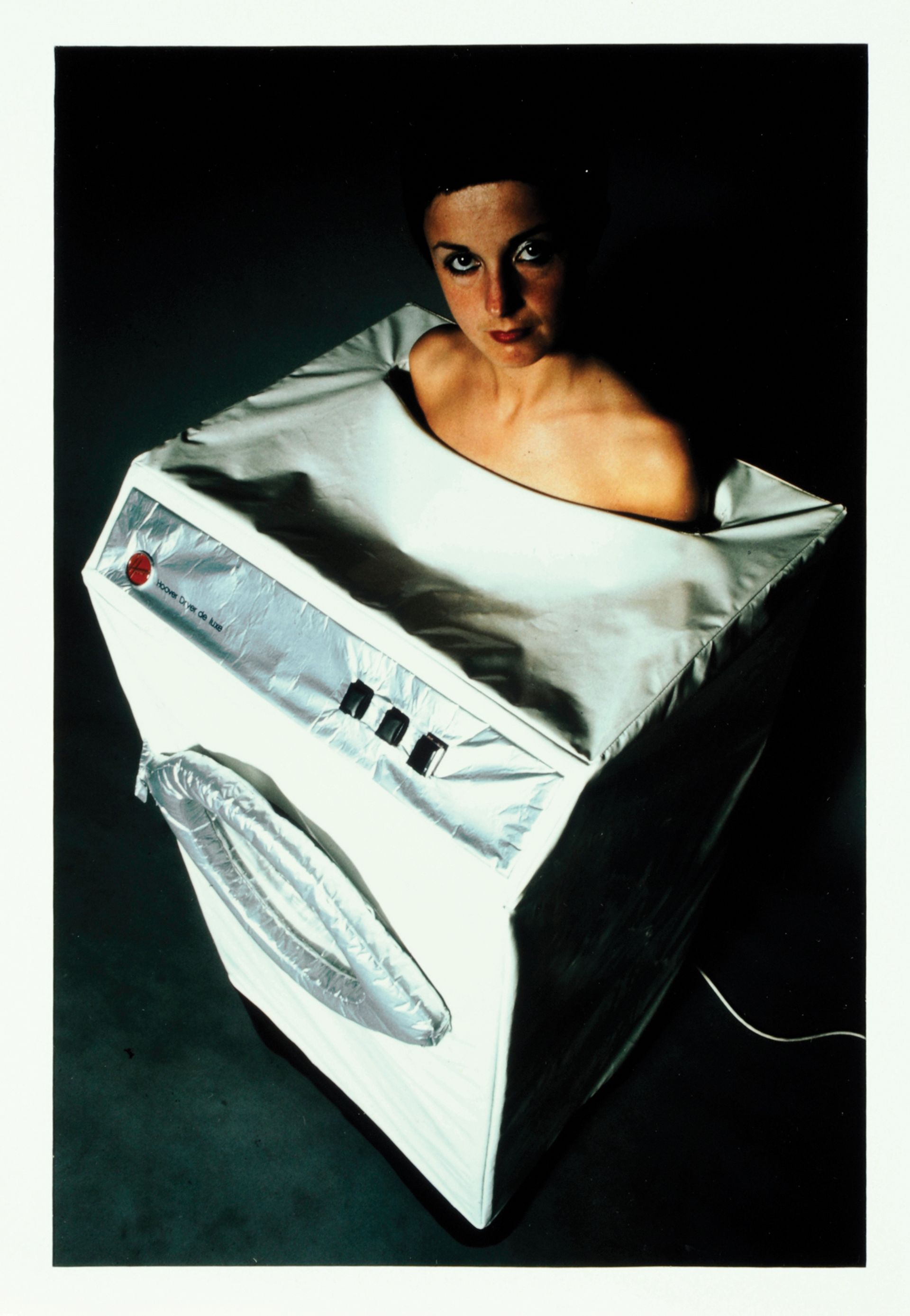

Helen Chadwick’s In The Kitchen, London (1977) Courtesy of the artist's estate and Richard Saltoun Gallery

Performance and interaction

A performative strand runs through much of the section. The photographic series In the Kitchen (1977) presents Chadwick’s wryly humorous parody of the enslaved domestic goddess. The series shows the artist dressed in elaborate and cumbersome sculptural costumes—an electric cooker, a fridge freezer, a sink unit and a washing machine—which conflate the female body with the domestic machine.

Twenty years later, the British Afro-Caribbean artist Sonia Boyce marked the shift from drawing and sculpture to more live, interactive work with the piece The Audition (1997), in which she invited participants to try on an afro wig. Each individual was photographed with and without the wig, and a selection of more than 400 of these photographs are being shown in Social Work.

“It was interesting in terms of people wanting to step into this imagined other identity, and all the questions it opened up around the connections between the Afro body being parodied and the clown,” Boyce says. “Since then I’ve realised that just the act of putting on an afro will make people laugh and they won’t know why; it has to do with minstrelsy and all that baggage.”

There are more deep-rooted historical resonances in the photographs, videos and performances of Searle, whose work explores how history and geography can be communicated through the human body. Still (2001) is a sequence of eight semi-transparent photographs of the naked artist kneeling and covered in flour, illuminated by a central light as she ritualistically kneads dough to make roti flatbread. “Covering myself in a white substance has obvious racial connotations,” she says. “But often there is a tendency to see this work only in relation to a South African context, which I think is limiting. After all, making roti is an activity that many different people can relate to, regardless of nationality.”

Nancy Spero’s Aztec Sahagun, New York (1979) Courtesy of Galerie Lelong

Although many of these artists are now established names—Boyce, for example, is a Royal Academician with an MBE—most of the pieces in Social Work have not had wide exposure. Boyce’s piece Audition is receiving only its third ever showing in 30 years and, although there is now a strong international market for Ringgold’s quilts, this is a relatively recent phenomenon. As the American artist remembers: “In 1980 my career as an artist was in limbo and I was so preoccupied at the time I hardly noticed I’d turned 50.” Duben admits that “it has been hellishly difficult”, and although Kelly’s Interim is now regarded as one of the most important feminist works of the 1980s, it is rarely shown in its entirety.

Raising consciousness

So, while this gang of eight may now occupy centre stage at Frieze London, there is still much work to be done – especially in the current climate, where #nosurprise, the art world equivalent to #metoo, fields numerous claims of discrimination and sexual abuse, and male artists continue to dominate the stables of commercial galleries and command the highest prices. “What’s happening now reminds me of the early 1970s,” Kelly says. “The subtleties have gone and there is continuous consciousness-raising that needs to happen.” She is still, however, happy to have her work included in this special section at Frieze: “In the middle of an art fair it’s good to have somewhere that is a little transcending, somewhere where people have time to think.” We can only hope that this pause for thought leads to wider repercussions.