In 1942, Dorothea Tanning painted the self-portrait that would catapult her into the Surrealist movement. Birthday shows her in fantastical costume with a winged creature at her feet, the gatekeeper to an infinite recession of open doors. The canvas was named in her New York studio by the émigré German Surrealist Max Ernst, who was scouting for female artists to participate in an exhibition at the gallery of Peggy Guggenheim, his then-wife. Within weeks, Ernst had moved in, and he and Tanning married four years later. (Guggenheim later quipped that she should have restricted the show, titled 31 Women, to 30 artists.)

Birthday, now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, will be the first work that visitors see in Tanning’s first museum survey, opening this week at the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid and travelling to Tate Modern in London in February 2019. The Spanish museum, which does not own any of her works, is committed to representing female artists through its exhibitions programme, says the show’s guest curator, Alyce Mahon, a Surrealism scholar at the University of Cambridge.

“Women artists. There is no such thing—or person. It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as ‘man artist’ or ‘elephant artist’”

“Women artists. There is no such thing—or person. It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as ‘man artist’ or ‘elephant artist’,” Tanning retorted in an interview in 1990 (then one of the last surviving Surrealists, she died at the age of 101 in 2012). She also disregarded distinctions between media, moving from the meticulous early paintings with which she is still most associated, such as Birthday and Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943), to set and costume designs for the ballet, soft fabric sculptures, prose and poetry.

The exhibition brings together more than 150 pieces spanning six decades, from Tanning’s commercial illustrations of the late 1930s to her fleshy painted nudes of the late 1980s. Visitors “can really devour a body of work” that has never before been mapped, Mahon says, and discover an artist all too often overshadowed by her husband’s fame. The Surrealist movement was criticised as misogynistic at the peak of second-wave feminism, but scholars and artists are now re-evaluating its “progressive exploration of gender politics” and its “queerness”, Mahon says.

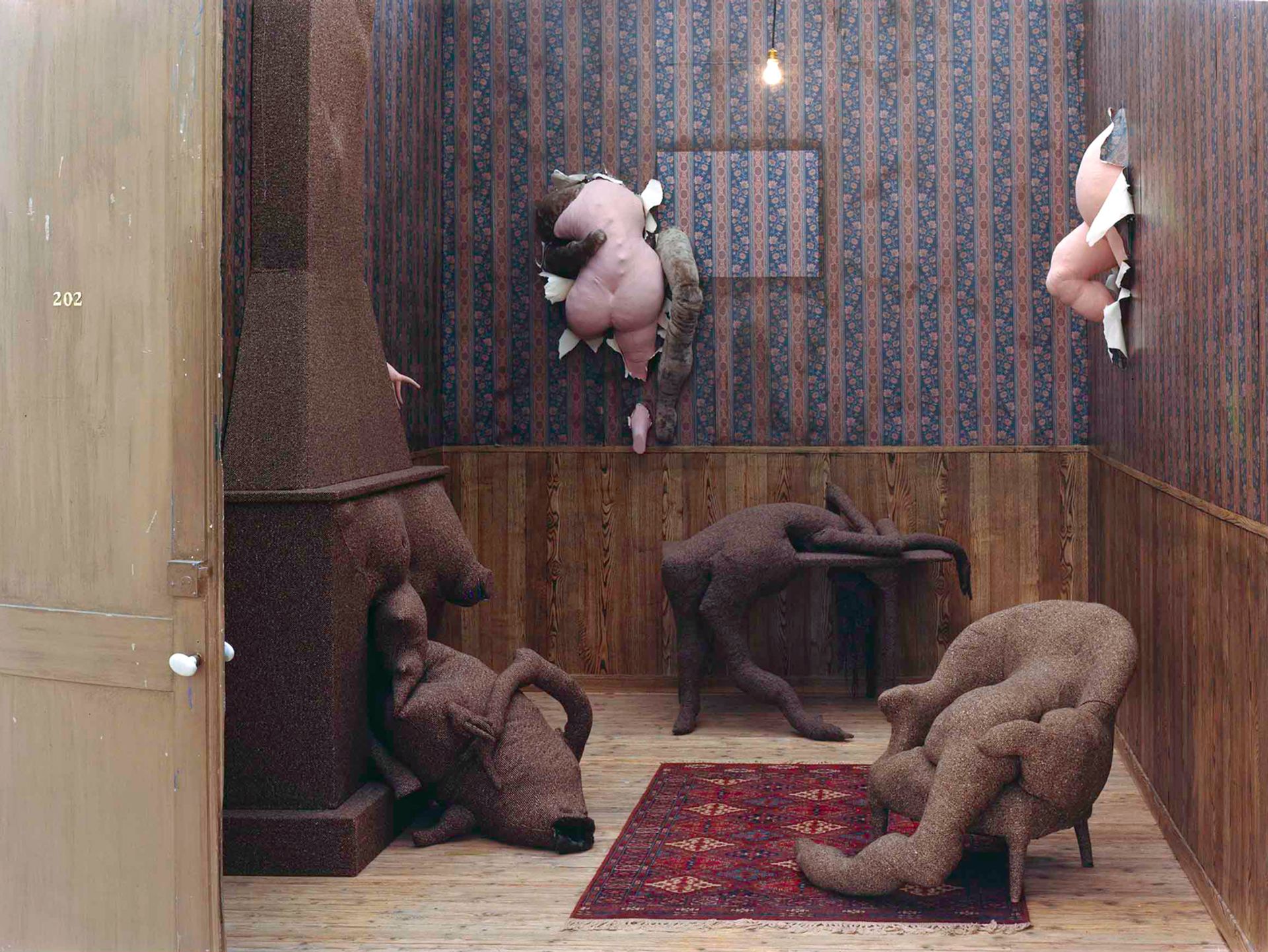

Tanning’s art “undermines the old idea of Surrealism just being about the objectification of women”, Mahon argues. Throughout her career and stylistic shifts, she “returns obsessively to the liberated female figure and makes domestic spaces uncanny”. The exhibition title, Behind the Door, Another Invisible Door, highlights the recurring motif of the door “not as a barrier, but a trope that is about opening the mind”—the Surrealist raison d’être. Tanning’s representations of femininity unleashed in the home—dreamy adolescent girls, monstrous mothers and headless nudes—culminated in her immersive installation, Poppy Hotel, Room 202 (1970-73), that will be on loan from the Centre Pompidou.

Dorothea Tanning’s Poppy Hotel, Room 202 (1970-73) © Centre Pompidou; Musée national d’art moderne

Stitched and stuffed for her 1974 retrospective in Paris, the cloth figures burst through the walls, “daring to enter new spaces”, Mahon says. The same could be said of Tanning, who left her small town in Illinois for New York, the Arizona desert, Paris and Provence. “I think people will be most surprised at how emancipatory her work is—and the life story you walk away with,” Mahon says. “Her energy and imagination knew no bounds right up until her last years. She never gathered dust.”

• Dorothea Tanning: Behind the Door, Another Invisible Door, Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, 3 October-7 January 2019; Tate Modern, London, 27 February-9 June 2019