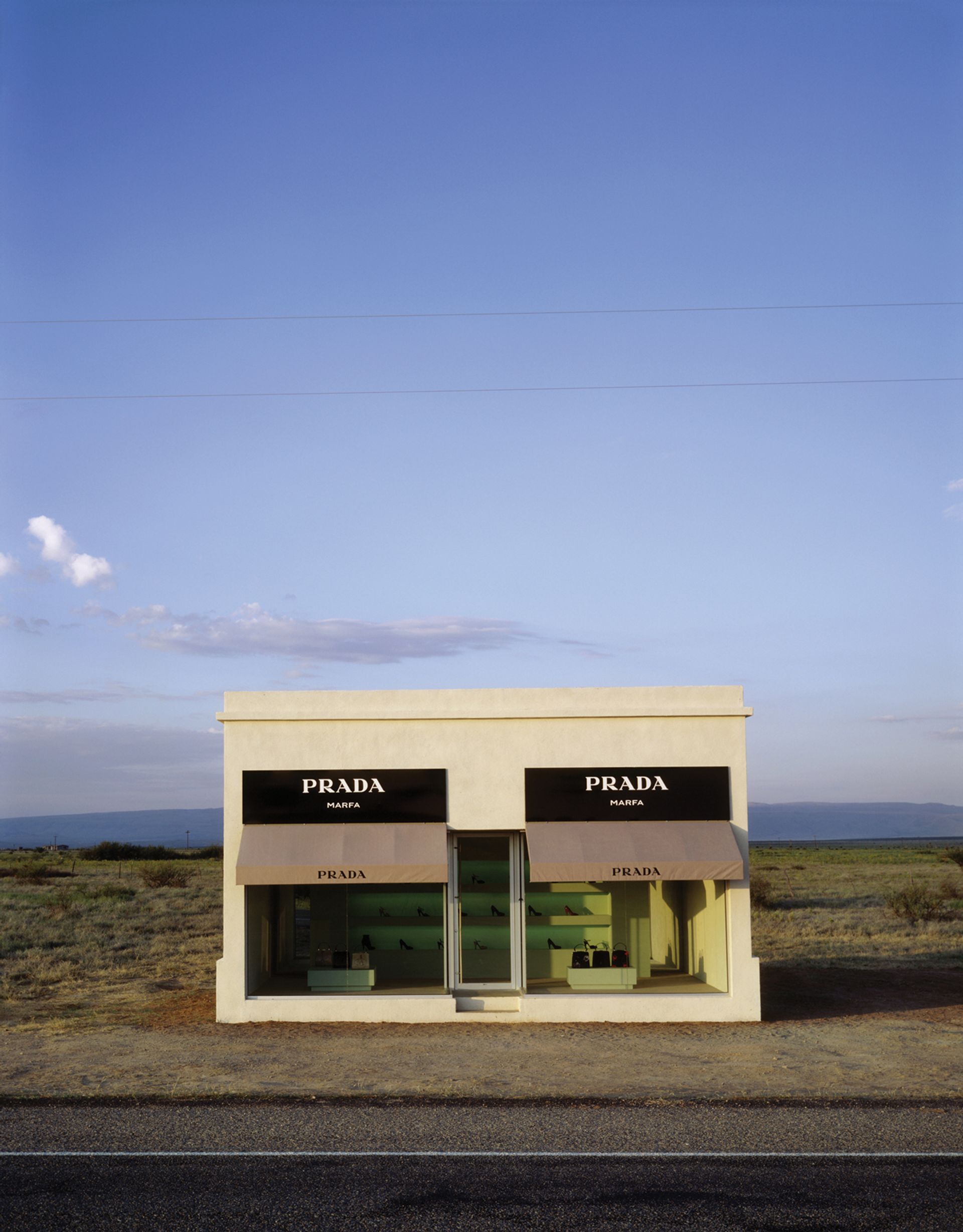

The Scandinavian duo Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset are among the most mischievously provocative artists working today. The pair have been working together since 1995, and whether they are installing a permanent Prada boutique in the Texan desert or converting the former textile galleries of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum into the memorabilia-packed home of a fictional elderly architect, their wittily subversive art challenges institutions and critiques pretensions and hypocrisy within the art world and society at large.

Funny they may be, but the art world takes them very seriously: in 2009, the pair were the first artists to occupy simultaneously two pavilions at the Venice Biennale, and in 2017, they became the first artists to curate the Istanbul Biennial. The duo’s first UK survey opens at the Whitechapel Gallery in east London this week, with works spanning more than two decades of collaboration and a major new site-specific commission—a derelict pool made in response to the gallery and its surroundings—all of which continue to expose the power structures that underpin our everyday lives.

The Art Newspaper: The title of your Whitechapel show is This Is How We Bite Our Tongue. What is the thinking behind this?

Ingar Dragset: The whole idea about us biting our tongue comes from this time when none of us really knows how to react or what to say, because there are so many crazy things going on and so many things to react to—and all the usual ways in which we have understood the world, and understood normal behaviour and our fellow citizens, just don’t count any more. Nothing is like it was. We as citizens don’t behave in the same way; our leaders don’t behave in the same way. Our identifications are not the same and nor are our ideas around the working class, sexuality, art, the environment, community, all these things.

Michael Elmgreen: This Is How We Bite Our Tongue has to do with something that happened first to an extreme degree within British culture and the whole idea around Brexit and has now spread out to the rest of the world, where people are so afraid and worried about how they present themselves to the public that they feel constantly uncomfortable in whatever context—even in relation to their friends and families. And that, of course, results in a tremendous anger that you see coming out, where people take it out on minorities and get very nostalgic about old-fashioned virtues that either never existed or were horribly repressive.

In The Welfare Show at the Serpentine Gallery in 2006, you converted the gallery into a series of dismal institutional public spaces that exuded a general air of social malaise. The world is now an infinitely scarier place; do you feel you are picking up where that show left off?

ME: The Welfare Show was about the problems around civic space and the show at the Whitechapel is about civic space not existing any more. So, at the Whitechapel, you come into this abandoned environment that has totally fallen apart; it has been bought up by investors and is waiting to be transformed into a private membership club. It is still a ruin and it is still abandoned, so it is also a psychological image of many of us: we are these old sentimental believers in the value of civic space, of communal places, and we are abandoned and left alone, waiting to be bought up by someone.

ID: We often take the institution itself, and its location and surroundings, as a starting point, and here we are responding to the immediate surroundings and what is happening to this area. The fact that this gallery started as an idea around education and civic space and bringing art and culture to the masses is very interesting. Hopefully, the Whitechapel is safe, but no space is secure for ever: we’ve seen so many playgrounds, civic spaces and public buildings bought up and transformed into condos or luxury living spaces or hotels.

Installation view of Elmgreen & Dragset's Whitechapel Pool Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Jack Hems

You’ve turned New York’s Bohen Foundation into a subway station, the Victoria Miro gallery into a nightclub and two Venice Biennale pavilions into the homes of fictitious art collectors. Why is it important to transform art spaces in this way?

ME: We often try to create a different environment in which the audience can experience the art, so it looks different from a normal exhibition space. There are many fantastic institutions in London, but if you go from one white cube to the next, and just see different artists’ work in settings that remind you of each other, you might be a little bit slowed down in your curiosity and your openness and your perception. So we try to pull people out of the routine of going to an art show and place them in a completely different environment, where suddenly it may be more possible to actually look at the art that is in this strange environment.

What is your working method? Do you have a system? You used to live together and now you don’t; has that changed how you work?

ID: The funny thing is that we never sat down and talked about a system. The way in which ideas come up is very fluid and comes from such different places: from travel, or seeing a work in a historical museum, or being upset by issues you read about in a newspaper article. Or it can be from a night out on the town, or literally looking out of the window, observing a neighbour smoking on the balcony in shorts. Chance observations trigger the dialogue.

ME: Now we are so old that we can’t even imagine another way of working in this lifetime. We are far too lazy to be one single artist: if we only did half of what we are doing, it would be really bad. One could say we are in it for the dialogue; that’s our working process. The endless conversations we have about ideas and how to execute them, about aesthetics, and about being upset about political matters, that is what creates the art. But when we work with other artists or when we work with curators or institutions, it’s also a dialogue, and there’s also the dialogue with the audience. The art is somehow an excuse for the dialogue, an excuse for an ongoing communication about things that matter.

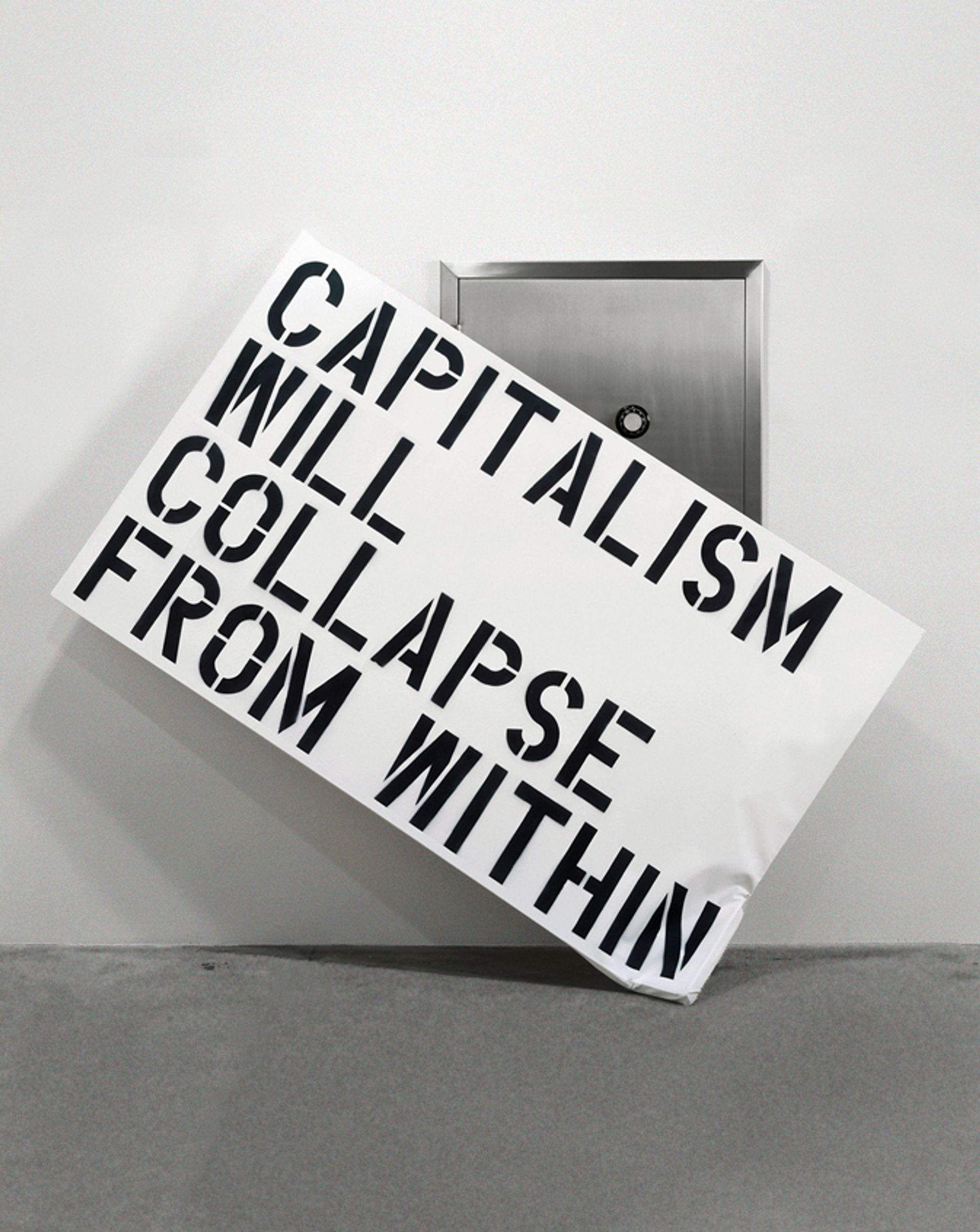

Capitalism will collapse from within (2003) Photo: Oren Slor; courtesy of the artists

How important is the fact that neither of you trained as an artist and that you both came to making art from other disciplines—Michael as a writer and a poet and Ingar from theatre and performance?

ID: One of the best things about coming a bit from the outside is that you are not so afraid of authority and you are perhaps not so respectful of rules, because you didn’t grow up with them. Once you know what the rules are, it is almost too late to abide by them.

ME: I am still struck by surprise at the art world’s ignorance and arrogance towards its audience. It’s the only art form that seems to fulfil itself within an internal introvert system of a very few. If you are in the theatre or if you are writing, you fucking need an audience, because if you don’t sell any books or you don’t have anyone in the theatre, you fail, and it’s embarrassing. I think that it is quite special for us to be coming from somewhere else. I don’t think you need to talk down to people, I don’t think you need to be populist or try to make hits or drag in millions of people, but I care about the average art-goer coming to my show as much as I care about a critic or a collector or a curator. I actually like the audience.

But how effective can art be? Does it have a purpose beyond reflecting back our awful world and causing us all to wring our hands some more?

ME: Art can give us hope because some idiots are making something that costs them a lot of effort for absolutely no reason, but they still think it’s worth it. That kind of behaviour is what is called civilisation. Doing these useless things is being civilised. What art can do is make us less fearful. If this institution dares to show Elmgreen & Dragset—two adult men who are saying that it is so important to play dolls’ houses with reality and to put so many resources into creating this kind of imagined universe for the spectators—then you, as an audience, can be allowed to be silly as well. You can be allowed to be free and not to care what certain people may say about your behaviour. So I think art can make you less fearful. Only fearful people are easy to manipulate by populist politicians.

ID: Art is a great place to keep the flame alive.

• Elmgreen & Dragset: This Is How We Bite Our Tongue, Whitechapel Gallery, London, until 13 January 2019

Biography:

Background Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset met in a nightclub in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1995—describing the encounter as “fatal attraction”—and started living and working together. Elmgreen, born in Copenhagen in 1961, was writing and performing poetry; Dragset, born in Trondheim, Norway, in 1969, was studying theatre. In 1997, they moved to Berlin, where they continue to live (although no longer together).

Milestones An ongoing series of installations called Powerless Structures since 1997 A full-sized model of a Modernist Kunsthalle at the Istanbul Biennial in 2001 A memorial to homosexual Holocaust victims in Berlin’s Tiergarten Park in 2003 Transforming New York’s Bohen Foundation into a subway station in 2004 Creating arguably their best-known work, Prada Marfa, in 2005 The debut of Drama Queens, a play about 20th-century art history, at Skulptur Projekte Münster in 2007 Presenting The Collectors at the Venice Biennale in 2009 A bronze sculpture of a boy on a rocking horse on the Fourth Plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square in 2011 Installing Han, a sculpture of a young boy, in Elsinore, Denmark, in 2012 The Public Art Fund’s presentation of Van Gogh’s Ear, an upended swimming pool, at New York’s Rockefeller Center in 2016 Curating the Istanbul Biennial in 2017

REPRESENTATION Victoria Miro, London; Massimo De Carlo, Milan; Galerie Perrotin, New York/Paris/Hong Kong; König Galerie, Berlin; Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen

Elmgreen & Dragset: Three key works

Prada Marfa Photo: James Evans; courtesy of the Art Production Fund, New York, Ballroom Marfa and the artists

Prada Marfa (2005)

This permanent sculpture of a fully stocked but sealed Prada boutique is in the Texan desert, 42km north-west of the city of Marfa. “It was a work about making experimental land art,” the artists say. “It was not only about how a Prada shop would look in the desert, it was also about how a desert would look with a Prada store, because the desert has also been commodified as the backdrop to road movies, to commercials… it was a work that was out of sight for everyone and then Instagram was invented and it went viral. It went in many directions and into many contexts that were completely unintended from our side.”

The Collectors: Nordic Pavilion, Venice Biennale Photo: Anders Sune Berg; courtesy of the Colección Helga de Alvear, Madrid/Cáceres

The Collectors: Nordic Pavilion, Venice Biennale (2009)

“We made the Nordic pavilion into the home of an elderly gay bachelor who seemed to have been having a really good life surrounding himself with younger men and works of art, but sadly, he ended up face down in a pool, with his Prada shoes and socks neatly left at the edge. Swimming pools have been an obsession for us because the pool is a place where we have an excuse for mingling and playing and interacting, and we dare to show each other our bodies. If we were to behave in the same way in central London, we would get arrested. And swimming pools are, in themselves, so absurd: trying to replicate something from nature that then becomes more popular than nature.”

Powerless Structures: Fig. 101 Photo: © James O. Jenkins

Powerless Structures: Fig. 101 (2012)

“We thought that we had to comment on the situation of Trafalgar Square, with all its statues of warlords and supposed heroes who were so tiny and insignificant even in their physical being that they had to put them on horseback. So we chose the opposite: a child at play, a child looking in his imagination to the future, and being very non-heroic, in a way. He is a more sensitive and fragile creature; it’s just the everyday heroics of growing up.”