In my many years of reporting on exhibitions and auctions, I have scoffed at the increasingly frequent assertion from members of the trade that collectors of contemporary art have branched out into Old Masters, finding the combination as palatable as chalk and cheese. Now even the Frick Collection in New York is planning to install contemporary art among its Vermeers, Rembrants and Veroneses. Yet it took David Zwirner’s current exhibition, Endless Enigma: Eight Centuries of Fantastic Art organised in collaboration with the Old Master dealer Nicholas Hall, to demonstrate how the possibilities of blending the old and the new can be an exciting, even inevitable development in collecting.

Taking its cue from Alfred Barr’s landmark 1936 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art, Endless Enigma finds common ground between artists separated by centuries, through 90-odd works—some from museums and private collections, but most for sale.

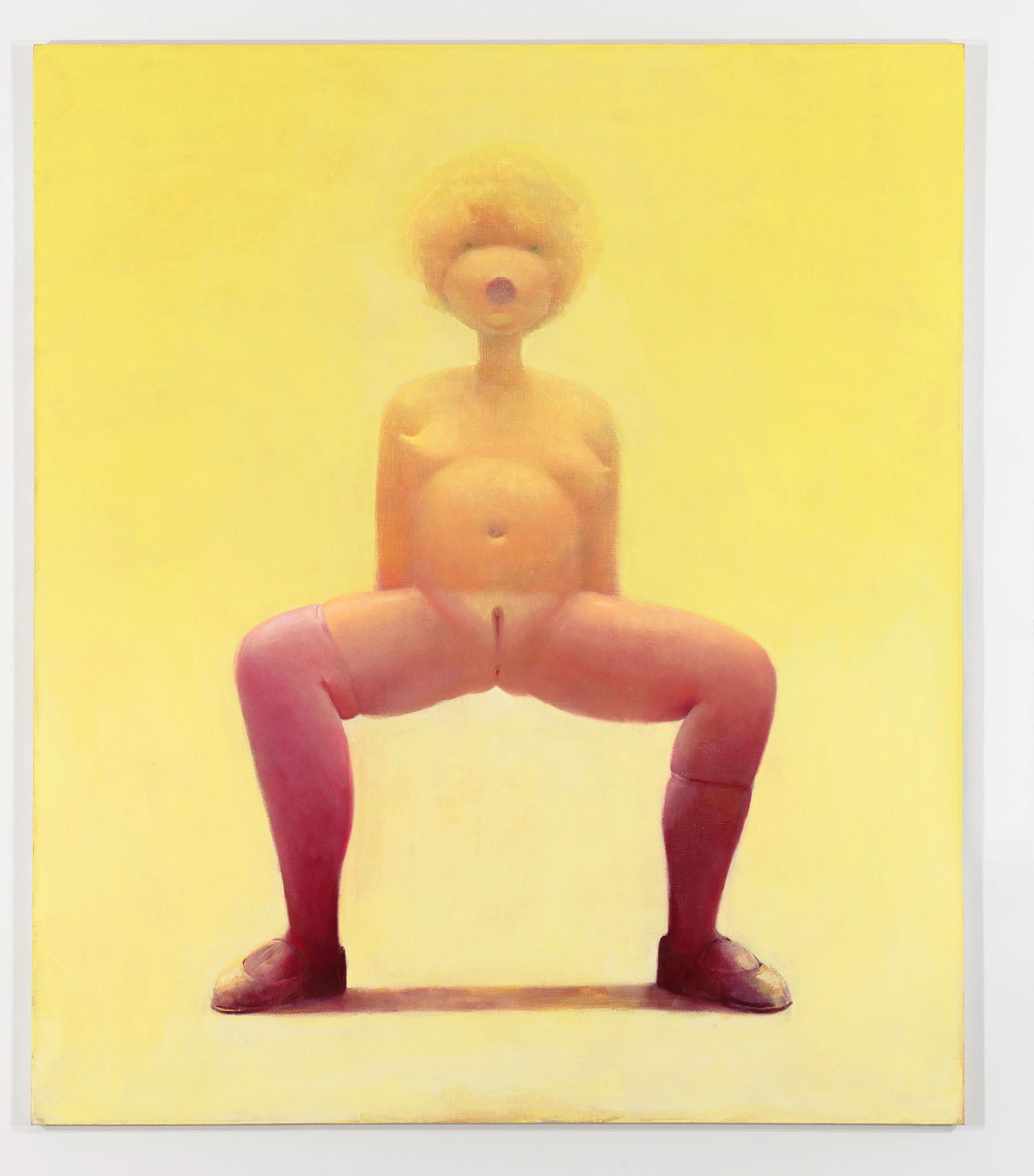

Lisa Yuskavage, Rorschach Blot (1995)

The first gallery, a surprisingly playful excursion in the representation of the nude, is dominated by a full-size, 16th-century copy of the central piece of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights and a churning millwheel of four push-pull nudes representing the Four Elements (1611), by the little-known Flemish Baroque painter Louis Finson (recently acquired by the Blaffer Foundation in Houston). These are comfortably joined by Louise Bourgeois’s Nature Study (1984), a silvered bronze kunstkammer object of a multi-breasted headless figure; Les Baigneuses (1959), a grimly determined group of nude swimmers by the underrated Leonor Fini; and paintings by René Magritte, Gustave Moreau, as well as two large canvases by Lisa Yuskavage of aggressively confrontational female figures. Everything works.

Wallace Putnam, Mask of the Traveler (1936) David Bowie Archive

A particular pleasure of the show are its discoveries of little known and anonymous artists, notably Mask of the Traveller (1936), a powerful plywood assemblage by Wallace Putnam which featured in Barr’s original Fantastic Art show (and is now owned by David Bowie's estate), with its seemingly random application of found street objects anticipating Robert Rauschenberg’s assemblages that would come 25 years later. Fantastiques (around 1830-40), a group of 25 watercolours of abstract splashes transformed with a carefree pen into dreamlike stews of unrelated figures, is attributed to the caricaturist Jean-Jacques Grandville, but seems to me to be the work of a talented unfettered outsider artist of the period.

Piero di Cosimo, The Finding of Vulcan on the Island of Lemnos (1490)

Piero di Cosimo’s extraordinary The Finding of Vulcan on the Island of Lemnos (around 1490), on loan from the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford—in itself reason enough to see the show—shares a room of the natural surreal with three boxes by Joseph Cornell from 1950; two life-size grisaille allegories by Leonor Fini of Painting and Architecture (1938-39), swaggering figures festooned with tools of their craft; and The Wings of Augury (1936), a dainty yet commanding mixed-media depiction of Daphne by the little-known British Surrealist sculptor Eileen Agar. Agar’s fantastical image made of wood, bronze, faux-jewels and feathers would be well appreciated by the eccentric Piero, who possessed an almost obsessive interest with the minutiae of the natural world, as seen in his carefully rendered birds and trees.

A room themed around images of the afterlife is anchored by James Ensor’s great Skeletons Warming Themselves (1889) from the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, joined by a ghostly oil on cardboard of Carnival Street Musicans by Jose Gutierrez Solana (around 1906); London (2005), a small panel by Francis Alÿs of a merry skeleton rattling a fence with a shinbone; a similarly sized panel by Michaël Borremans Fire From the Sun (2017), where sluggish figures aimlessly crawl in the heat; and an impression of Martin Schongauer’s The Temptation of St Anthony (around 1475).

James Ensor, Skeletons Warming Themselves (1889)

Aided by both the uniformity of the graphic medium and their absence of strong colour, a small room of prints and drawings offers perhaps the smoothest transitions between Classic and Modern, with drawings by William Blake, Victor Hugo, Francisco de Goya, and Odilon Redon's cheerfully disturbing Head of a Cyclops (around 1880), joined by Black Herald (1924), a delicate work by Paul Klee. In its heady blend of Old Masters, Modern and contemporary, Endless Enigma is not an exhibition to be seen and processed at once, but repays several visits for all its quiet relationships to be explored and engaged. And once again—everything works.

• Endless Enigma: Eight Centuries of Fantastic Art, David Zwirner, New York, until 27 October