On Wednesdays and Saturdays since early August, visitors to the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo have been able to watch conservator Delfina Fagnani at work on its “new” Mantegna. The €40,000 restoration, sponsored by the Rotary Club of Bergamo South, will remain public throughout September and is expected to continue until November. In May it was announced that the curator Giovanni Valagussa had re-examined the Accademia’s forgotten panel of the Resurrection of Christ (around 1492-93) and found it to be an original Mantegna.

The work had been acquired in 1846 and its attribution to Andrea Mantegna was confirmed by Charles Eastlake, the first director of London’s National Gallery. A few years later, however, the art historian Giovanni Morelli and others contested the attribution, seeing the painting as “ruined by restoration”. In 1910, it was classified as a studio work and in 1912, the expert Bernard Berenson listed it among the “copies of lost works”. After the Second World War, the Accademia put the panel in storage as a Mantuan painter’s copy after Mantegna.

While compiling an entry on the painting for the museum’s new catalogue of 14th- and 15th-century paintings, Valagussa noticed that a cross painted in gold at the panel’s lower edge, between the rocks, “obviously belonged to another painting”, he says. “I thought the most likely scene was a Descent into Limbo. I compared [the panel] with paintings of that subject of the same size, and when I put it next to Mantegna’s Descent into Limbo [in a private collection] on Photoshop, I discovered that the rocky arch divided between the two panels matched up perfectly.”

Valagussa contacted Keith Christiansen from the European paintings department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, who replied enthusiastically within minutes. The Bergamo panel, obscured by old varnish and restorations, could be reattributed to Mantegna and to the same painting as The Descent into Limbo (1492). The authorship of that work has never been doubted since it resurfaced in the 20th century; it was sold at Sotheby’s in New York in 2003 for $28.6m. Giovanni Agosti, the art historian who co-organised the Louvre’s Mantegna show in 2008 and is one of the few to have seen the Bergamo painting in the flesh, also backed the new attribution.

How could such a work have been forgotten? “There wasn’t even a colour photograph,” Valagussa says. “No one had been able to observe that minuscule cross.” Another detail caught his eye: on the back, halfway up, are two sawn-off nails. “I thought of a crossbar that had been removed, but the position was totally anomalous. It could, however, be the trace of a frame applied before painting to reinforce the panel, which is just 8mm thick. It must have been vertical, given the location of the nails.”

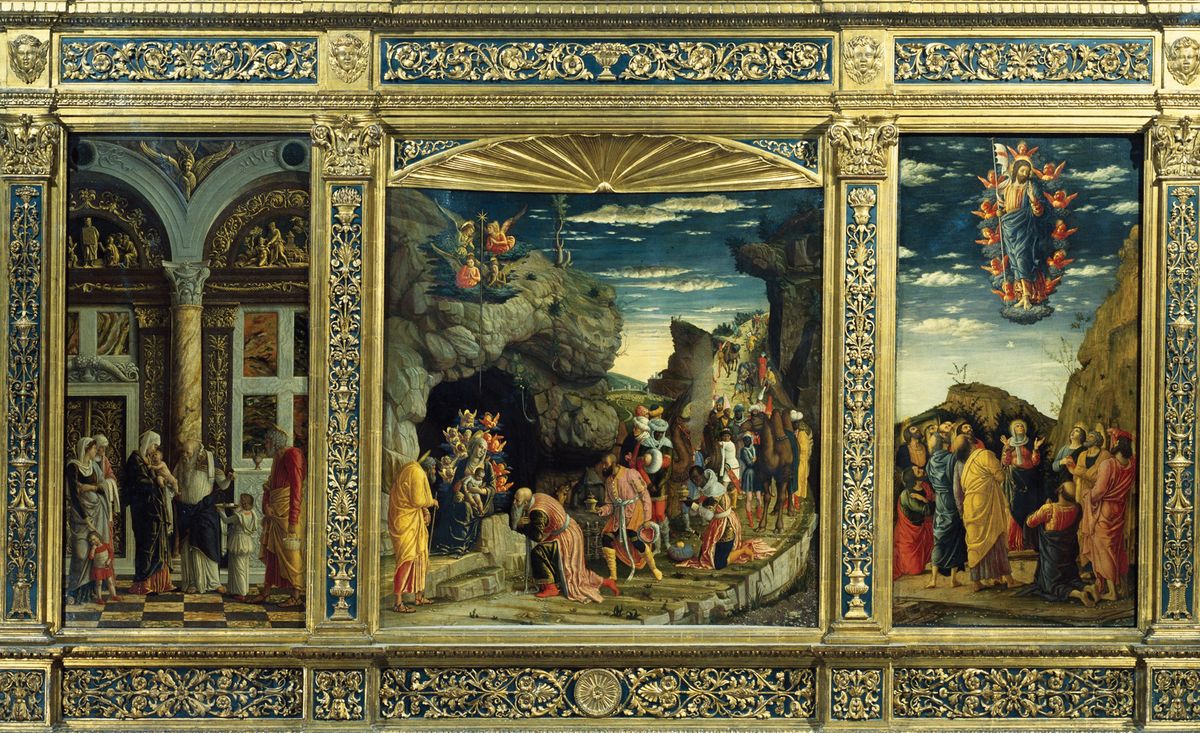

Valagussa believes that the divided paintings may have formed the wing of a polyptych altarpiece. One theory under consideration—for a show Valagussa is planning next year to reunite the Resurrection and the Descent—is that the Bergamo panel relates to the Mantegna triptych in the Uffizi in Florence, which was itself reunited in the 19th century.

“We have speculated on a provenance from the lost chapel of the Castle of St George in Mantua,” Valagussa says. Mantegna decorated the private chapel for the Gonzaga family in the early 1460s; it was destroyed in the 16th century. Among the paintings identified with the decorative scheme to date are the Museo del Prado’s Death of the Virgin; its missing upper fragment, Christ with the Soul of the Virgin, in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Ferrara; and the Uffizi’s triptych’s panels: The Adoration of the Magi, The Ascension of Christ and The Circumcision. All date to an earlier moment in Mantegna’s work, but the Accademia Carrara’s panel could prove to be a later addition.

The Bergamo Panel Photo: © Accademia Carrara

Meanwhile, the first attempts to remove the amber-coloured patina are revealing Mantegna’s crisp and transparent colours. The painting had already been treated by Paola Artoni, the head of the Laniac Centre at the University of Verona, and Miquel Herrero of the University of Lleida in Spain, using infrared reflectography, while the pigments were analysed with X-ray fluorescence spectrometry and with a microscope.

“The data has confirmed Valagussa’s theories,” they say. “The cross is indeed pertinent, the diagnostic evidence of a skilled underdrawing confirms it as an autograph work, and the palette corresponds perfectly to the master’s.”

What is more, Valagussa says, the infrared images of the underdrawing for the standing soldier on the right, “reveal that the drawn muscles of the naked body were later ‘dressed’ in paint—a process that was typical of Mantegna”.