Two close members of Thomas Gainsborough’s family were murdered over a financial dispute, new research has revealed. The Art Newspaper has tracked down threatening letters sent in 1738, just before the separate murders took place. One of the warnings was directed at the artist’s cousin: “We will either shoot him or hang him up in gibbets, damn the… rogue’s arse.”

The main research on the artist’s youth and the murders has been conducted over four years by Mark Bills, the director of Gainsborough’s House in Sudbury, Suffolk, in preparation for an exhibition that is due to open there in October. His show focuses on the early years of Thomas Gainsborough, who was born in Sudbury in 1727, the son of a wool merchant, and who went on to become one of the leading painters of his time.

The murder victims were the artist’s uncle (1678-1739), who lived in a neighbouring street in Sudbury, and his cousin (1709-39), who then worked in London. Both were also named Thomas. Biographers of the artist since the mid-19th century had failed to note these murders in the family.

Bills points out that the uncle played a key role in “shaping the life of the artist and his family through his support and direction”. The young artist, who was 11 at the time of the murders, would have been only too aware of the traumatic events in his close-knit family. Revelations about the murders will therefore make it important to reassess the artist’s early years.

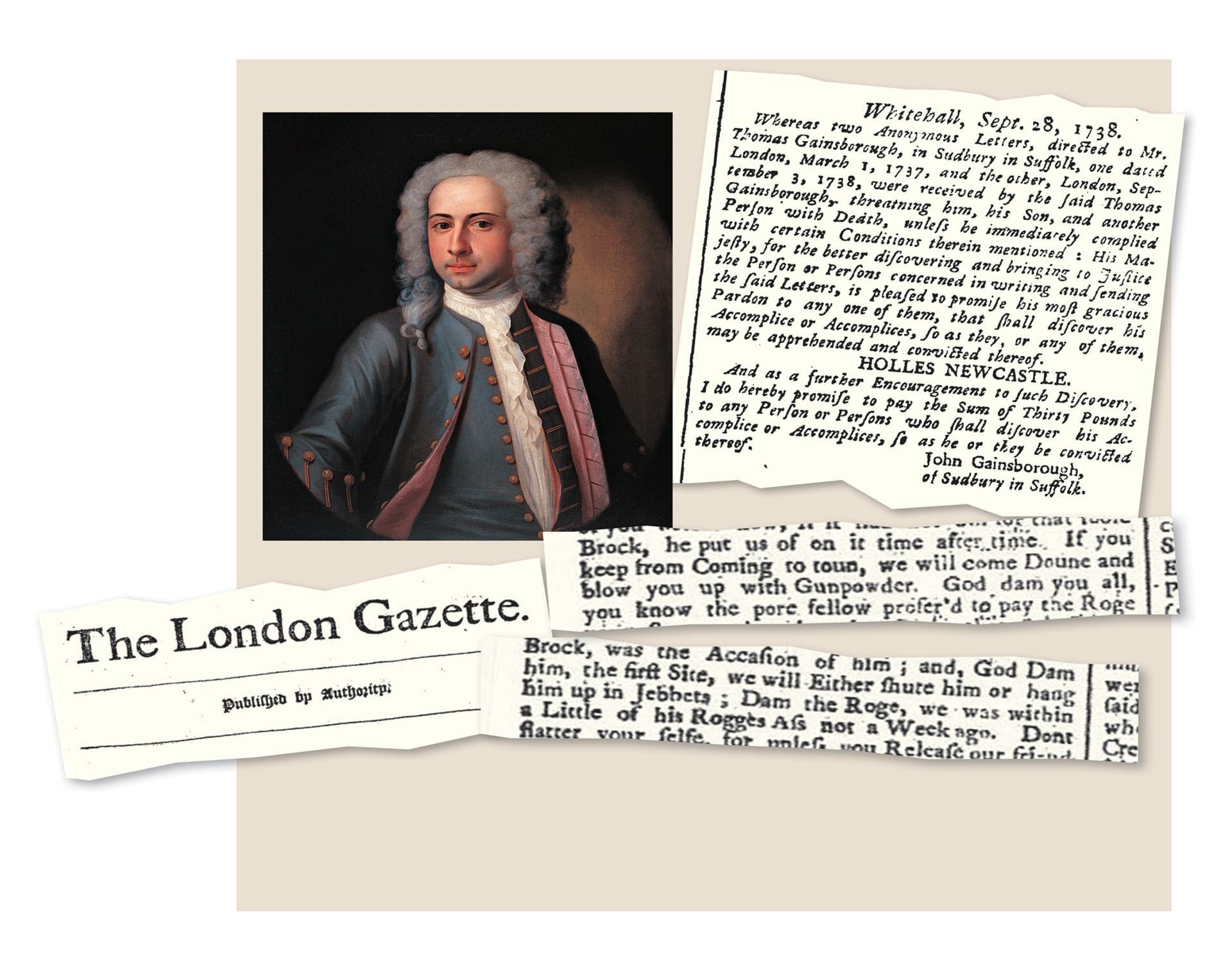

A new Gainsborough House show features J.T. Heins’s 1731 portrait of the artist’s murdered cousin (left). The threats were published in the London Gazette, discovered by Mark Bills, and in the Daily Gazetteer tracked down by The Art Newspaper. Heins portrait: © Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, Suffolk. London Gazette excerpts: courtesy of the Gazette

Brutal threats

Bills discovered a report in the London Gazette (26 September 1738), referring to two threatening letters addressed to the artist’s uncle. These letters were forwarded to the publication by John Gainsborough, the artist’s father, in an attempt to catch the gang. Through the pages of the London Gazette, John offered a reward of £30 and promised not to prosecute anyone who came forward with information to enable their accomplices to be caught.

Thanks to Bills’s discovery of the existence of the two letters, The Art Newspaper was able to track down the actual texts, which were published a month later in the Daily Gazetteer (24 October 1738).

The first anonymous letter, sent from London on 1 March 1738, accused the artist’s uncle and cousin of having “ruined” financially their friend Richard Brock. The uncle and son were then pursuing a debt that Brock owed to the Gainsboroughs’ former business partner, John Barnard.

The first letter included a tough demand that the debt should not be pursued. If it was, the artist’s uncle and cousin would be killed. “We will come down and blow you up with gunpowder, God damn you,” or else they would be fed “a meal that you will not like”. The son was singled out for special attention, with the letter relating that one week earlier, the anonymous writer and his gang had been just behind the “rogue’s arse”. The letter ended with the words “revenge is sweet”. The uncle and cousin must have felt seriously threatened, since a few months afterwards, they both wrote their wills.

An even more threatening letter was sent six months later, on 3 September 1738, warning the son about his “ominous end”. The anonymous writer said they had recently seen him “upon the road”, but had decided against killing him then “for the sake of the poor woman”, his wife, who was accompanying him. They warned that they would not be intimidated by the fact that he was “carrying his brace of pistols”, since there were a dozen of them. An ultimatum was issued: the Gainsboroughs must drop their claim against Brock within a week.

The Brewer’s Map of Sudbury (1714; detail), showing the artist’s country town. Gainsborough left for London in 1740, a year after the two murders © Sudbury Town Council, Suffolk

Ensuing murders

The ultimatum expired on 10 September. Five days later, the cousin was buried. As he was just 29, it must be assumed in these circumstances that he was shot or poisoned, rather than dying of natural causes. Given that his body had to be transported from London to Sudbury and the funeral arrangements made, he would have been murdered just hours after the deadline passed.

The artist’s uncle remained undeterred by his son’s murder and continued to pursue the debt. Exactly six months later, he too met his own death, in a London pub. In a brief report in the Weekly Miscellany (17 March 1739), found by The Art Newspaper, it is recorded: “March 10, died, at the Golden Fleece in Cornhill, Mr Gainsborough, a crepe [wool] factor of Sudbury.”

This well-known inn lay close to the place where the Sudbury coaches stopped. Although the newspaper did not report the cause of death, it is highly likely to have been murder, particularly since it occurred in a pub. Had it been a shooting, this would probably have been noted, so surreptitious poisoning after the victim had drunk a few beers is perhaps more likely.

As far as we can establish, the men behind the two murders were never caught, although further research might uncover legal records. The gang comprised a dozen men, but even the £30 reward did not tempt any of them to go to the authorities.

Gainsborough’s Wooded Landscape with Old Peasant and Donkeys, outside a Barn, Ploughshare and Distant Church (around 1755). The work is in the exhibition opening in Sudbury in October © Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, Suffolk

Impact on young Gainsborough

The intriguing question is what impact the murders had on the artist. It must have been highly traumatic for the family, but in financial terms, John Gainsborough, the artist’s father, gained. Four years earlier, he had faced bankruptcy, but he received an inheritance after the deaths. This enabled him to spend more on his precocious son.

Bills says the two murders “give us a whole new perspective on Gainsborough’s early life”. They provided the family with the financial resources to send the young Thomas to London in 1740, to study under the engraver Hubert François Gravelot.

Emotionally, however, the murders must have been extremely upsetting, particularly for a youth. Presumably the boy would have attended both funerals. And because of their close family links, there must have been fears that John and his children might be next on the hit list. It is even possible that the artist’s father felt that his son would be safer in anonymous London rather than in the small town of Sudbury, where an individual’s movements could easily be followed.

For the young artist, it would have been emotionally difficult to leave the comfort of home after these terrible events, even if he also wanted to escape from Sudbury and put the deaths behind him. As Bills says, “on arriving in London, the young Thomas must have been aware as he got off the coach from Sudbury that his uncle had been murdered in the pub around the corner”. In his exhibition and catalogue, where more details are given, Bills will reveal more regarding his discoveries of the murders and “give a context for the artist’s early work”.

• Early Gainsborough: from the Obscurity of a Country Town, Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, Suffolk, 20 October-17 February 2019