“Extreme violence” will grace the quiet walls of London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery this month in the first major UK exhibition of the Spanish Baroque artist Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652).

“These pictures were done to shock, to create visual impact in their day,” says the exhibition’s co-curator Xavier Bray. But they were also “pictures for discussion”. Ribera: Art of Violence focuses on eight monumental paintings, such as Apollo and Marsyas (1637) from the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples, in a thematic hang that will also include drawings, prints and even a piece of real human skin.

The “scenes of extreme violence are informed by what [Ribera] would have seen on the streets of Rome and Naples”, Bray says. Although the artist was born near Valencia, he is recorded as being in Rome aged just 16 before moving to Naples—then under Spanish rule—where he made his name, mostly making works for a noble and merchant class of patrons.

While Ribera is often seen as an heir to Caravaggio, the Spaniard was also “steeped in classicism”, Bray says. “But those contradictions go hand-in-hand and are what make his pictures powerful in their realism but beautiful in their aesthetic realisation.”

Jusepe de Ribera's Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (1644) © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2018; Photo: Calveras/Mérida/Sagristà

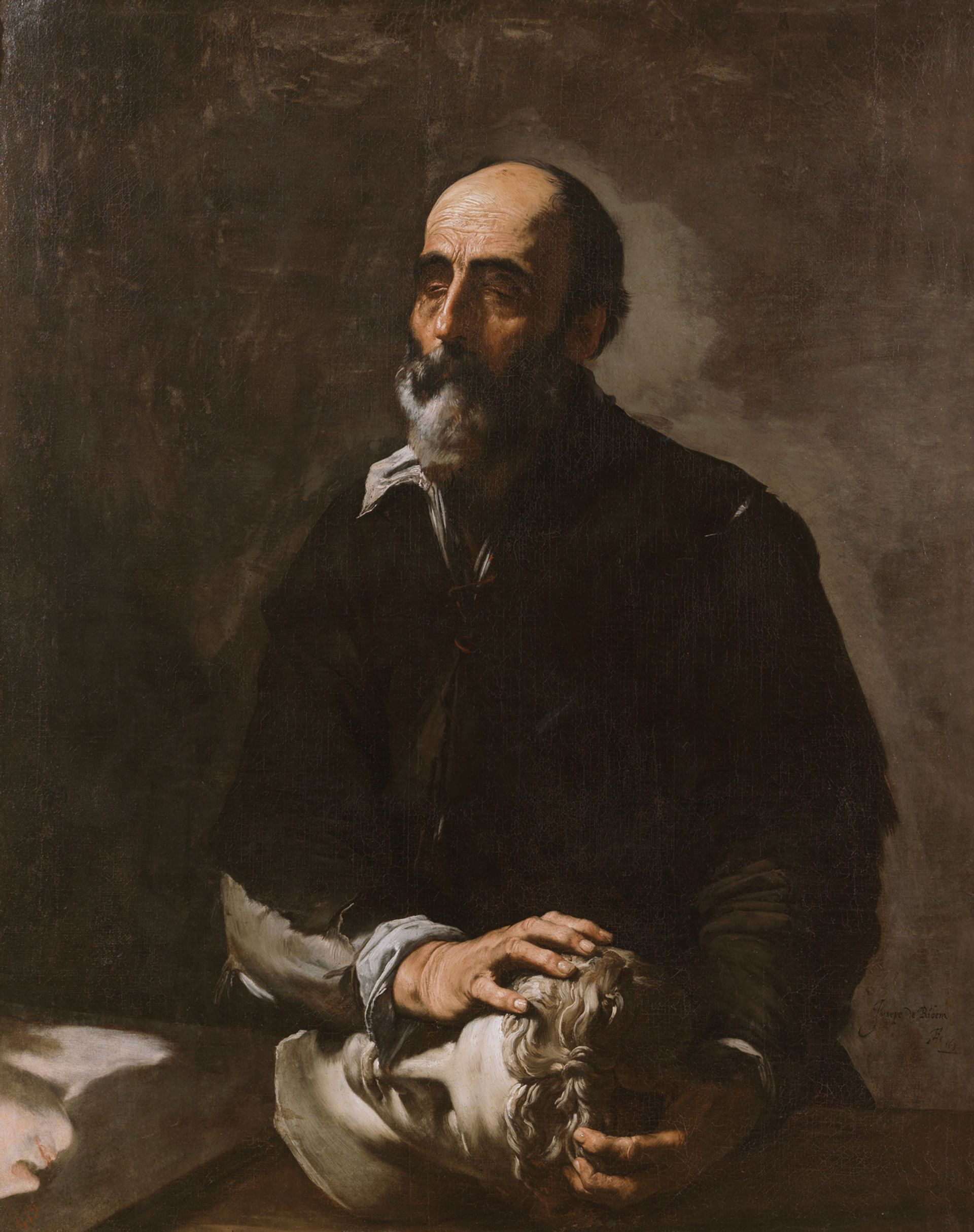

Ribera plays with these two sides of his work in the Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (1644), on loan from the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. The artist places the decapitated marble head of Apollo “very significantly” in the foreground of the painting, Bray says. “And in doing so he is building up a visual, almost art historical, argument of ideal art—led by Apollo and the idealism of Raphael and Michelangelo—being toppled by this new visual language that is realism.”

The curators have borrowed a marble head of Apollo from the British Museum and are proposing that this is the same one that Ribera painted from, which also appears in a 1628 version of the Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew and in The Sense of Touch (1632). Unfortunately, the museum would not allow the sculpture to be displayed on its back as it appears in the paintings, Bray says.

Ribera realised early on that Saint Bartholomew was the perfect “leitmotif”, Bray says. The show includes three paintings, one drawing and one print of the flayed saint, but all are markedly different in their handling of the scene. The subject allowed Ribera to show off his skill at painting human skin, at conveying the emotions and terror felt by Bartholomew, and also the reality of the execution method: “the way the executioners perform the ritual, as if they are butchers going about their daily task,” Brays says.

Jusepe de Ribera’s The Sense of Touch (1632) with the marble head of Apollo © Museo Nacional del Prado

Bray and his fellow curator Edward Payne are “keen to bring out an element in the exhibition of skin being a sensory organ” and will include a piece of real human skin from the 19th century. “Removing [skin] and revealing what is beneath it can be full on,” Bray says. But “we felt strongly that it would wake up the viewer to comprehend what Ribera was working with.”

The exhibition’s main sponsor is the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica.

• Ribera: Art of Violence, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 26 September-27 January 2019