Brace yourself, traditionalists: Henry Clay Frick’s venerable Old Master paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints and porcelain seem destined for a change of scene.

In an unusual game of musical chairs, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Frick Collection announced today (21 September) that the Met will vacate the Brutalist Breuer building on Madison Avenue in 2020. Its departure will make way for the Frick to move in late that year while its mansion undergoes a renovation and expansion five blocks away.

The Met has leased the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1966 Breuer building as a temporary exhibition space for Modern and contemporary art since 2015, when the Whitney moved into its new home downtown. The Met says it is now ready to resume plans for expanding galleries devoted to Modern and contemporary art at its Fifth Avenue flagship building.

“The Met Breuer has provided—and continues to provide—a great laboratory [for where] the Met is going,” says Max Hollein, who took over as the Met’s director last month. But “it all leads back to having Modern and contemporary art with a very robust programme within the Fifth Avenue building”.

The Frick is taking over the Breuer space after brokering a “sub-tenancy” deal with the Met, which had been due to stay in the building until 2023, says the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg. “It’s like if you’re renting an apartment, if you have a sublet clause, as long as you take care of it and do everything you’re supposed to do, it’s fine,” he says. “And they have a sublet cause.” The Frick and the Met did not disclose the financial terms, but it has been reported that the lease could be renewed; Weinberg says the Whitney, which owns the building, has no plans to return to the Breuer yet.

The Frick says the move will allow it to avoid closing entirely to the public during the construction work on its 1914 stately mansion, which is expected to start in mid- to late 2020. The expansion still awaits public approval by a city zoning agency, the Board of Standards and Appeals, and the Frick does not submit its application to the board until late this month, says Ian Wardropper, the Frick’s director.

“It’s not yet a done deal,” but “I fully expect that this is going to happen,” he says of the move. He adds that he expects the Frick to remain in the Breuer building for “two years plus”.

The Fragonard Room in the Frick Collection's 1914 stately mansion in New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

Old Masters in a Modern home

For months, the Frick had been scouting for potential storage spaces and conferring with other museums about where it might display part of its collection during the $160m construction project, Wardropper says. “It was surprising and immensely gratifying when the Met Breuer came into play.”

“Now we’ll have the option to have the entire collection in one building under our supervision around the clock,” he says.

Daniel Weiss, the Met’s president and chief executive, says the institutions discussed the possibility of doing “joint programming” in the Breuer early on, but as the conversations evolved, it made more sense for the Frick to take over the building. “We didn’t start chasing the possibility of getting out of the lease early,” he says, but museum officials realised “maybe there’s a way [the Frick] would benefit from the building, as we’re thinking about moving in a different direction”.

The building, a starkly imposing inverted ziggurat clad in dark grey granite designed by Marcel Breuer, may seem an unlikely venue for the Frick’s vintage collection of some 1,400 Old Master paintings, sculptures, works on paper and decorative arts, now ensconced in rich period interiors.

“This is like the collection going on vacation once in 100 years,” Wardropper says. “It can let its hair down a bit and present itself a little differently.”

“We might put things in different configurations and we may do some exhibitions we’d never do” at the Frick, he says. The goal, he adds, is “enticing people to look closely.”

“I think in the beginning people are going to be really curious—what does the Frick look like in a distinguished Brutalist building?” he says.

He also notes that the Met had displayed Old Masters in two major exhibitions since it moved into the building: Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible and Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300-Now).

The Met has estimated its average annual operating expenses for the first two years in the Breuer building at around $17m. Wardropper says the Frick would not spend “anywhere near that” but declined to give a figure. He emphasises that its budget for the renovation period has always included expenditures for storage of the collection and temporary office space. The Met would be responsible for covering any difference in the expenses, but the agreement with the Frick would save it around $45m.

Before the Met began its programming at the Breuer, it embarked on a $13m renovation of the building. Wardropper says he does not plan to undertake any further work. “The Met did a beautiful job restoring this important building,” he says. “We’re going to work for the most part with what’s there”—perhaps “constructing a few walls here and there”.

Patrons of the Frick’s renowned Art Reference Library, with a collection of 228,000 titles and 3,300 periodicals, will be able to request materials a day in advance for perusal in a reading room at the Breuer, the Frick director says. The books will all be housed in a storage depot upstate where 25% of the materials are already kept.

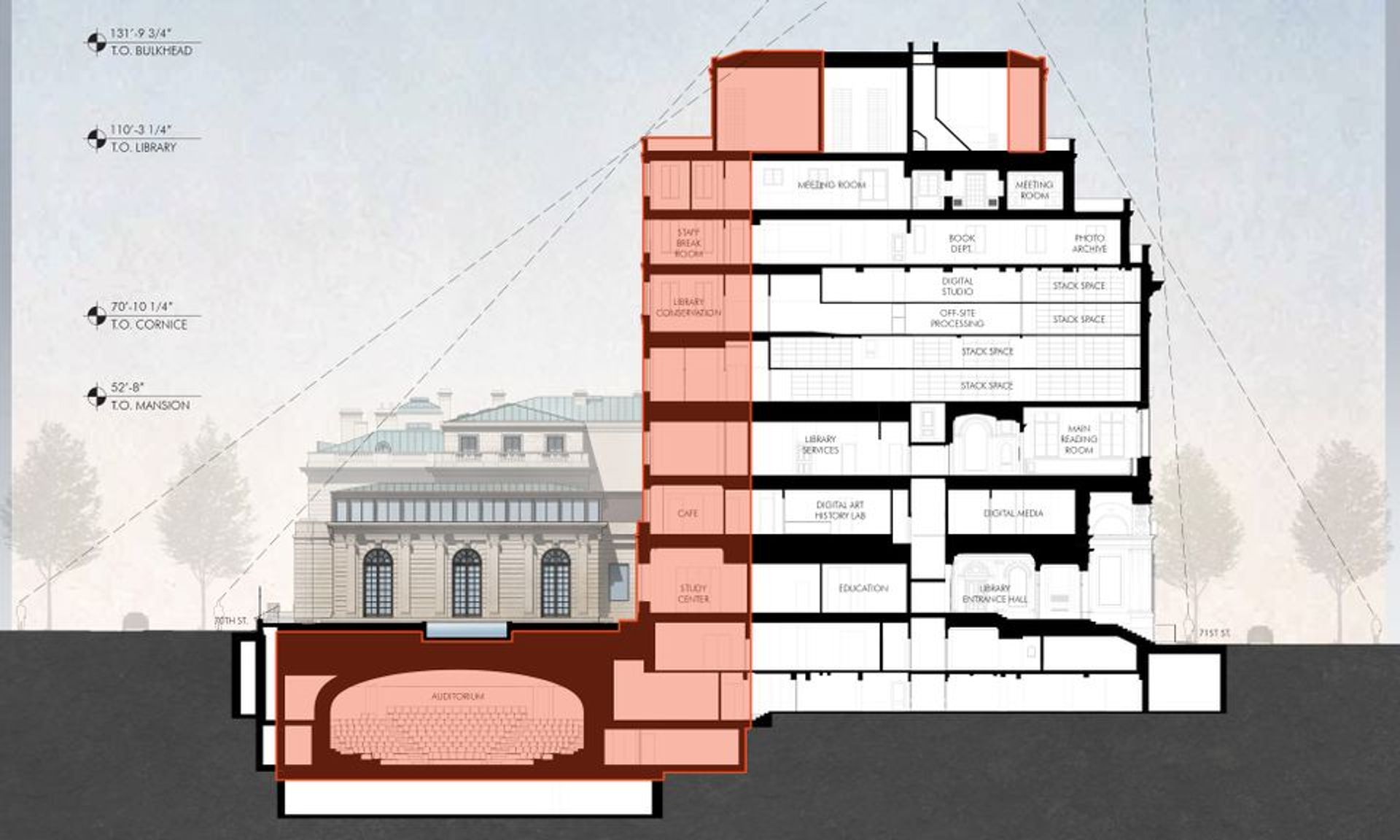

The proposed extension of the Frick Collection Library and underground auditorium Courtesy of Selldorf Architects

The museum is currently in the midst of a capital campaign to cover the $160m renovation and expansion, designed by the architect Annabelle Selldorf in association with the firm Beyer Blinder Belle. Wardropper says that more than half of that figure had been raised so far.

He describes the museum’s trustees as “enthusiastic” about the move.

“We’re going to be able to continue to connect with our audience,” Wardropper says. “If we’d been completely closed for three years, people might begin to forget about us.”

The Chipperfield expansion, take two

The Met, meanwhile, is gearing up to expand contemporary art initiatives at its Fifth Avenue building. Planning for a new $600 million contemporary wing there was put on hold early last year in the midst of a soaring budget deficit that contributed to the resignation of Thomas Campbell as director.

Since then, says Weiss, the museum has made “great progress” toward balancing its budget by 2020 and tackling the challenge of replacing the skylights in the museum’s European paintings galleries. “We have a new director, we have a strong financial foundation, and we have our infrastructure issues behind us, or at least under control,” he says. “So we thought it was the right time to revisit this question about Modern and contemporary.”

As a result, the Met has renewed discussions with the architect David Chipperfield on a new wing that will cost less than $500m but have the same amount of gallery space as the architect’s initial plan, Weiss says. He adds: “The next phase of the work is to make sure that the design that we develop is entirely consistent with [Max Hollein’s] vision—and that’s what we’re doing now.”

Hollein says he is exploring the possibility of a doing an annual sculpture commission for the facade of the Fifth Avenue building—similar to the popular rooftop series © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Hollein says he has already met with Chipperfield and that the expansion is “clearly one of my priorities for the next couple of months”. He adds that he is also exploring the possibility of a doing an annual sculpture commission for the facade of the Fifth Avenue building—similar to the popular rooftop series—and installations of contemporary art throughout common areas.

Weiss says that the expansion will allow the museum “to continue the work we’ve done at the Breuer in Modern and contemporary art all while celebrating the encyclopaedic nature” of the Met.

“I think fundamentally the work we did at the Breuer has changed this institution for the good, in an enduring way,” he says.