“When you don’t have all the information, you’re left to fill in the blanks, and so people come up with these crazy theories,” says Doug Eklund, the co-curator of possibly the first ever exhibition to tackle art and conspiracy theories. “The way that I look at the subject of conspiracy is, it’s about aspects of history that are hidden,” Eklund says. “I think of it as almost a political occult.”

Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy at the Met Breuer includes around 70 works by 30 artists, made between 1969 and 2016 (up to, but not including, the last presidential election), looking at covert power and the ways governments and citizens interact.

With the advent of the internet, conspiracy has “gone from being super-latent, super-underground, super-subcultural—just the interest of people on the margins—[to being] mainstream, in a way,” Eklund says.

While the show might seem timely in the era of “fake news”, it has been in the works since 2010, when Eklund first brainstormed the idea with the artist Mike Kelley, who died in 2012.

According to Eklund, approaches to conspiracy tend to fall into two categories: the “forensic, fact-based work” of artists such as Hans Haacke, Jenny Holzer and Mark Lombardi, and “artists who are trying to capture the rabbit-hole aspect of the psychological experience of conspiracy”, including names from the California Institute of Art, such as Kelley and Sue Williams.

The exhibition is supported by Andrea Krantz and Harvey Sawikin, and James and Vivian Zelter.

• Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy, Met Breuer, New York, 18 September-6 January 2019

Three conspiracy theories tackled in the show

Sarah Anne Johnson's House on Fire (2009) © Sarah Anne Johnson

CIA mind control programme

Sarah Anne Johnson, House on Fire (2009)

“The thing that amazes me is, when I started working on the show [in 2010], the MKUltra project was the ultimate tinfoil hat topic—only real conspiracy nerds would even believe this,” says the curator Doug Eklund. In the 1950s, the Canadian artist Sarah Anne Johnson’s grandmother, Velma Orlikow, was given years of “treatments” including LSD and induced sleep, permanently traumatising her. They took place at the Allan Memorial Institute in Montreal, and were later discovered to have been part of a CIA-funded brainwashing experiment. Johnson’s mixed-media work takes a cheery yellow doll’s house and turns it into a hellish scene, based on her grandmother’s hallucinations.

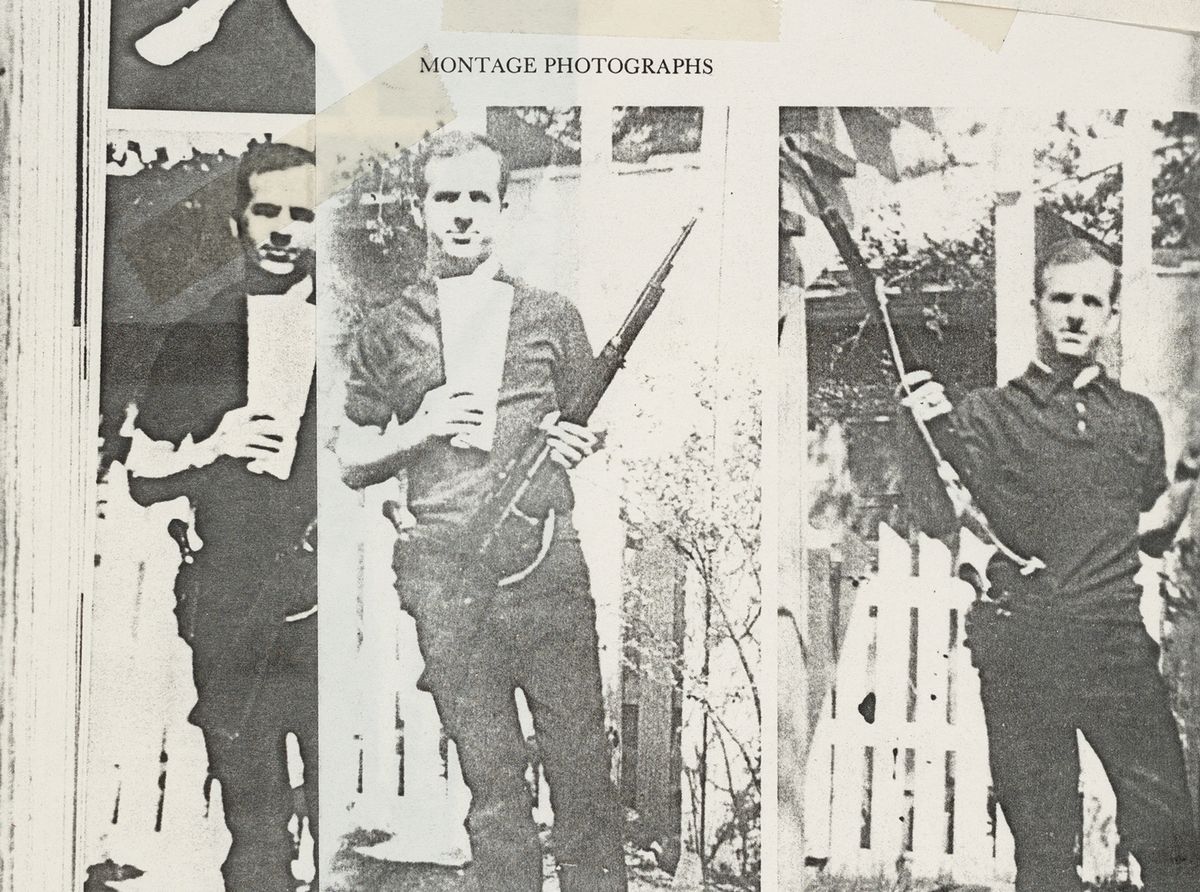

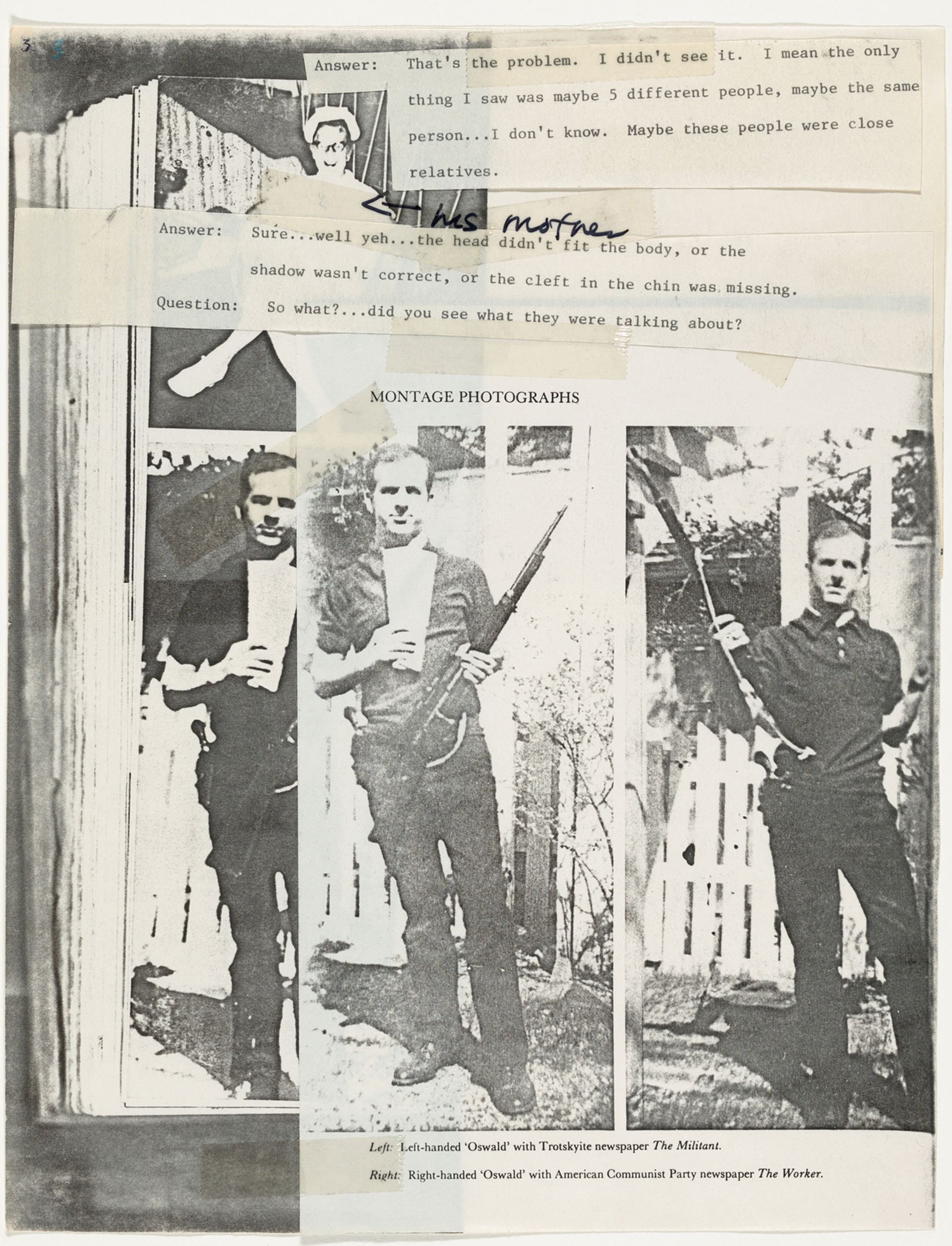

Lutz Bacher's The Lee Harvey Oswald Interview (1976) © Lutz Bacher; courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

Assassination of John F. Kennedy

Lutz Bacher, The Lee Harvey Oswald Interview (1976)

Mimicking the “ragged cut-and-paste aesthetic” of subcultures, this “self-interview”, 18-part collage of photocopied documents and images of Lee Harvey Oswald “looks like conspiracy theory the way we recognise it”, Eklund says. Unlike the CIA’s MKUltra, conspiracies about the 1963 assassination of President Kennedy “will never be verified in the ways that a covert [government] programme [was] eventually made known”, he adds.

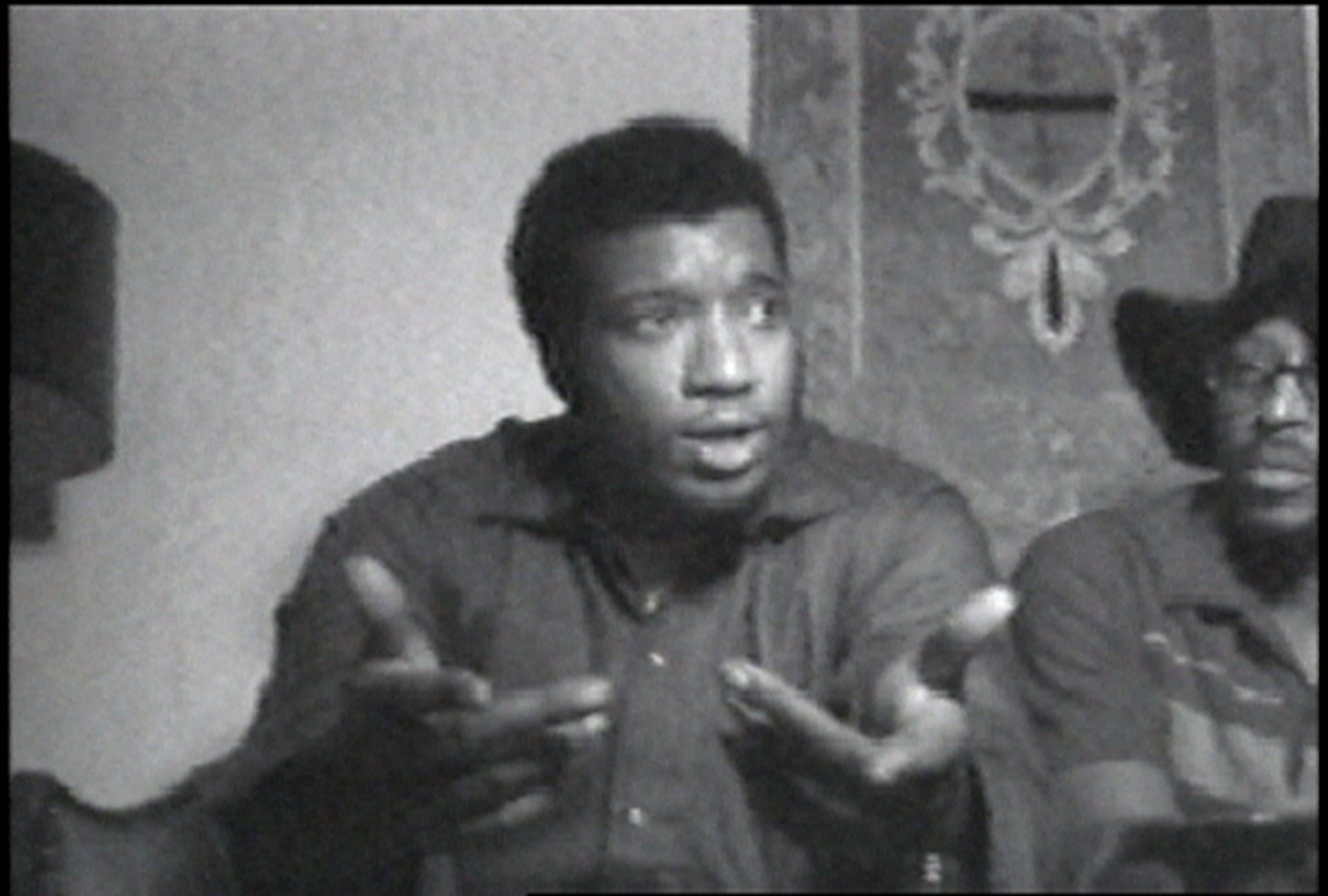

A still from Videofreex's Fred Hampton: Black Panthers in Chicago (1969) © Videofreex; courtesy of Video Data Bank at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago

COINTELPRO (counterintelligence programme) and the assassination of Black Panther leaders

Videofreex, Fred Hampton: Black Panthers in Chicago (1969)

This interview with Fred Hampton, aged 21, the chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, is “harrowing—because it’s a month before he was shot”, Eklund says. “He says in the video, ‘I’ll be dead in a couple of months’.” Hampton was killed by the Chicago police in an FBI-orchestrated arms raid, after being drugged by his bodyguard, a counterintelligence operative. At the time, the Black Panthers had renounced violence in favour of community programmes like free breakfasts for children. “That was much more dangerous to the status quo,” Eklund says.