Julian Schnabel’s new film on Van Gogh, which premiered in Venice earlier this week, may be artistic—but it pushes beyond the boundaries of truth. The New York-based artist and filmmaker suggests in At Eternity’s Gate that the Dutchman was shot by a local teenager and that 65 sketches which surfaced two years ago are authentic. Both points are simply wrong.

Murder or suicide?

A rusted Lefaucheux revolver, dug up in a field at Auvers in around 1960—and believed to be the gun which killed the artist Private collection

The argument that Van Gogh was shot by René Secrétan, a 16-year-old boy, was first put forward in a 2011 biography by two American writers, Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith. Although the 953-page work is meticulously researched and adds considerably to our knowledge, their appendix on “A Note on Vincent’s Fatal Wounding” created sensationalist headlines. Not specifying whether it was murder or manslaughter, the authors argue that it was Secrétan who fired the shot in Auvers-sur-Oise on 27 July 1890, which killed the artist two days later.

The most detailed refutation of the Naifeh/Smith theory is an article by two respected specialists at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, Louis van Tilborgh and Teio Meedendorp, published in the Burlington Magazine in July 2013. They forensically analyse the evidence, examining the relations between Vincent and his brother Theo in the artist’s final weeks and the letter found on his body. Their conclusion is that it was suicide, as has always been assumed.

For me, the most convincing evidence for suicide is that this is what was believed by Theo and the artist’s colleagues. It is also what Vincent himself said, if we are to believe the words of his loyal friend Emile Bernard. In a letter to the critic Albert Aurier, Bernard wrote two days after the funeral, which he had attended: “his suicide had been absolutely deliberate and that he had done it in complete lucidity”. This is what Theo had told Bernard. Additional evidence is the fact that the artist also appears to have attempted suicide while at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, a few months earlier.

At that time suicide was regarded as sinful, which is why the church in Auvers refused to allow its hearse to be used to carry Van Gogh’s body up the hill to the cemetery. Why would the grieving Theo have accepted the death of his beloved brother as suicide if it was murder?

Real or fake?

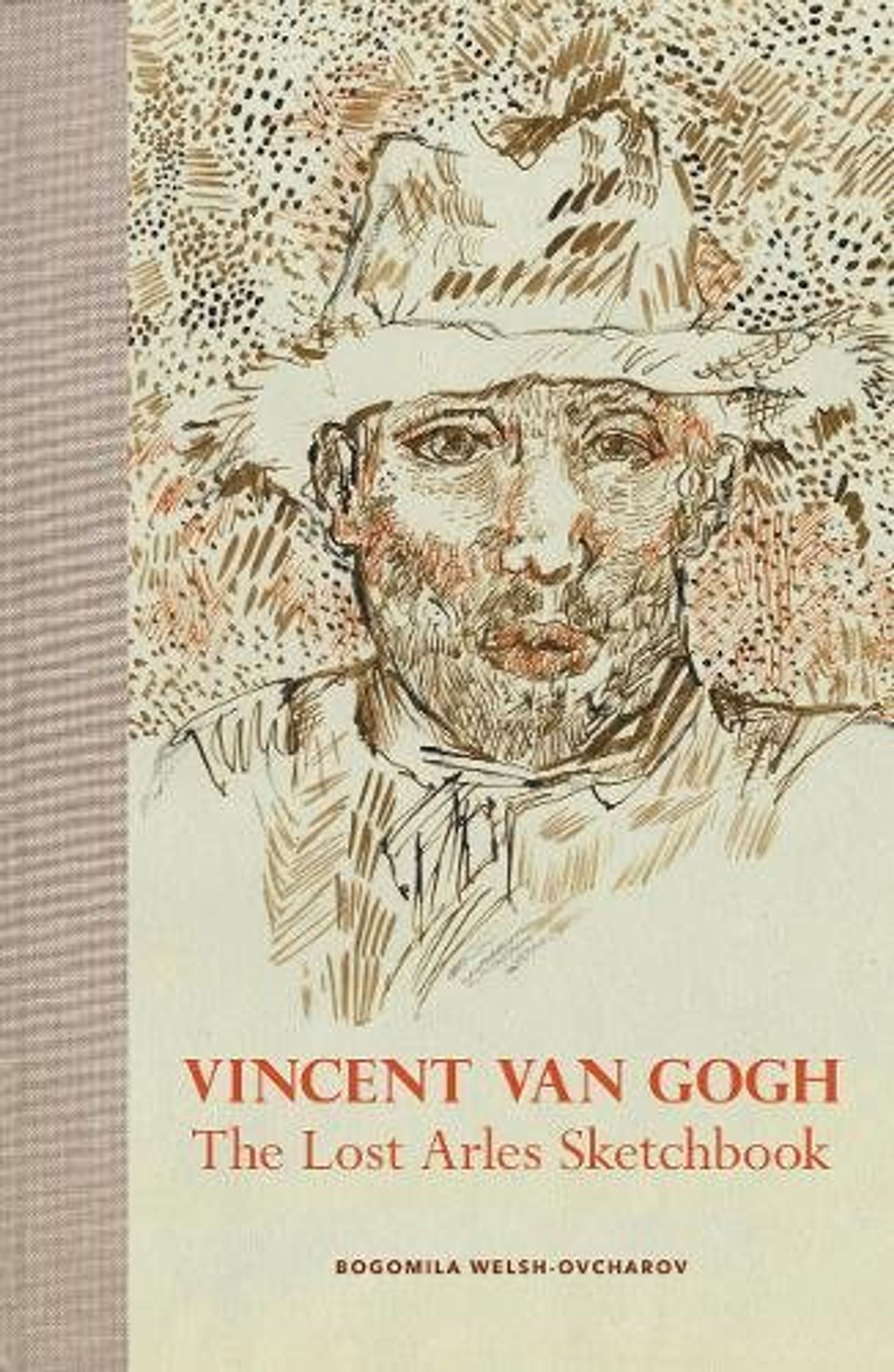

Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook, by Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, published by Abrams in 2016

The other controversial suggestion in At Eternity’s Gate is that the so-called Arles Sketchbook is authentic. This set of 64 drawings was said to have belonged to Marie Ginoux, who ran the Café de la Gare where Van Gogh had lodged in Arles. They were published in 2016 in a book by the distinguished Canadian scholar Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov.

In February 2010 I was approached about the drawings, three years before Welsh-Ovcharov became involved. At that time I felt there was insufficient evidence to suggest they were by Van Gogh. After the sketchbook was eventually published, the Van Gogh Museum considered them and concluded that the sketches “were not made by Van Gogh” and are “much later imitations of Van Gogh’s drawings by someone inspired by reproductions”.

The museum pointed to problems over the type of ink, the apparent discolouration of the ink, the type of pen or brush used, topographical errors in the sketches, the style, the order in which the disbound sketchbook had been reconstructed and the lack of a firm provenance.

Returning to Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate, there is no reason why an artist/filmmaker should not use their imagination to say something fresh about an historical figure, but it is important that we do not accept this as necessarily representing the truth. Lust for Life, a 1955 film based on a 1934 novel, created a whole set of myths about the “mad” artist that still percolate the public’s perception of Van Gogh. Schnabel admits that his film is “fiction” and he may well have created an interpretation which gives us new insights into Van Gogh’s life and the process of artistic creativity—but let’s hope that At Eternity’s Gate will not end up creating a new set of myths. Anyway, let's await the general release of the film in the US and UK, to see Schnabel’s take on this most intriguing of artists.

• For my account of Van Gogh’s period in Arles, see Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US)

• This week a new Van Gogh exhibition opened just outside Copenhagen, at the ARKEN Museum for Moderne Kunst, until 20 January

• For more on Julian Schnabel's film At Eternity Gate see the Venice Film Festival website