Matthew Landrus’s view on the contribution of Bernardino Luini to the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi was recently revealed in the Guardian (6 August). The Art Newspaper invited Landrus to expand on his theory and tell us why the picture should rightly be attributed to Leonardo and studio

Bernardino Luini: Christ among the Doctors (around 1510-22) Holwell Carr Bequest

The Louvre Abu Dhabi’s Salvator Mundi—which I believe is by Leonardo da Vinci and his studio—is best understood in the context of the picture’s early copies and similar paintings. Ludwig Heydenreich’s 1964 essay remains the most comprehensive treatment of Leonardo-related Salvator Mundis, which he claims were initiated by a Leonardo cartoon (a large-scale preparatory drawing), rather than an original painting. This view still lies at the heart of the debate about whether any of the Salvator Mundi variants can be attributed wholesale to Leonardo.

As part of a critical appraisal, a lengthier study would address the studio context with historical research, connoisseurship and technical and scientific analyses. I offer here notes on Leonardo’s studio, taken from a forthcoming essay (though not addressed in my newly updated book on Leonardo).

Although Leonardo received assistance from painters and apprentices from as early as 1483, he is traditionally the only author, or the primary author, of many of those projects. Around 1495-98, for example, he supposedly painted a Salvator Mundi (destroyed around 1603) in a lunette above a doorway between the Confraternity and the church of the Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, a fresco project likely requiring a cartoon and assistance from the painters in his studio. Two paintings of his design for a Salvator Mundi were produced with similar cartoons and in associated studios: the Abu Dhabi version, now attributed to Leonardo, and the “De Ganay” version (previously in the De Ganay collection in Paris), now attributed to Leonardo’s studio or Marco d’Oggiono. The De Ganay painting was also controversially attributed to Leonardo by Joanne Snow-Smith in 1978, who believed that it was “painted between 1507 and 1513, when the artist was in the service of Louis XII”.

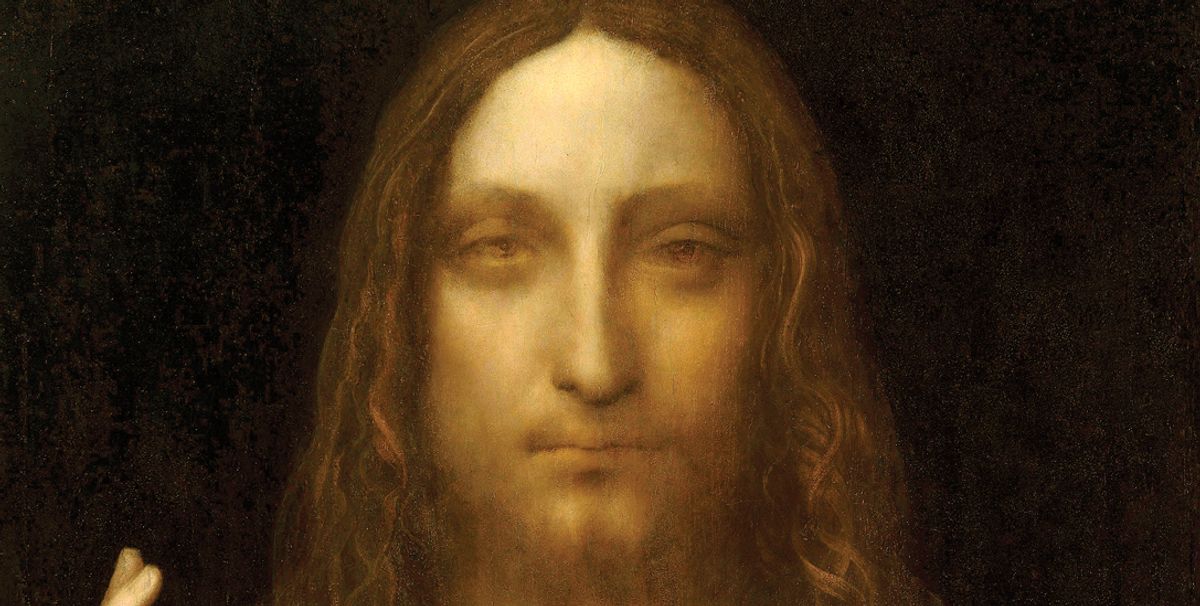

When the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi was recorded in the Cook collection in 1900, it was attributed to Bernardino Luini (around 1480-1532), and then in 1958 to another of Leonardo’s followers, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (1467-1516). Carmen Bambach (2012) noted that “much of the original painting surface may be by Boltraffio, but with passages done by Leonardo himself, namely Christ’s proper right blessing hand, portions of the sleeve, his left hand and the crystal orb he holds”. Boltraffio and Luini have been traditionally considered the best of the so-called leonardeschi. But Boltraffio often overworked surfaces so that they do not appear to absorb light in the subtle manner Leonardo, Luini and Leonardo’s pupil Salaì (1480-1524) could manage.

Leonardo’s notebook entries suggest that Salaì, Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono (around 1475-1530) joined his studio in 1490-91, though one or both of the latter painters also worked with their own studios. In 1491, d’Oggiono collaborated with Boltraffio on the impressive Resurrection of Christ (in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) and around 1500-16 they collaborated with Giampietrino (around 1495-1549), and potentially Leonardo, on a copy of the latter’s Last Supper (now in the Royal Academy of Arts, London). Boltraffio’s continued support in 1510 is implied by a thoughtful notebook entry by Leonardo: “1510 / On the 26th of September, Antonio [Boltraffio?] broke his leg; he has to stay still for 40 days”.

Studio of Leonardo da Vinci: Salvator Mundi (De Ganay version, around 1512) Public domain

The Abu Dhabi and De Ganay compositions are almost the same size, and copy Leonardo’s red chalk drawings of the chasuble and sleeve on two folios (around 1510-15, according to Carlo Pedretti) in the Windsor Royal Library, though not in exact proportions. The gold filigree collar band and crossed stole are, however, in the same locations in each painting, with nearly identical filigree geometry and treatment with white heightening. Using Photoshop, I have overlapped false colour scans of the De Ganay painting onto the Abu Dhabi painting, showing the identical proportions of the filigree bands, similar proportions of the crystal ball, and slightly different proportions of Christ’s right hand. Whereas the bands align on both paintings, locations of the hands and crystal ball are partially shifted, indicating the use of more than one cartoon. And the meticulous handling of paint is similar for the vestments, hair and filigree bands. The Abu Dhabi painting is on walnut, which Leonardo used primarily in Milan, and the De Ganay painting may also be on walnut, identified as a “nut wood”. Work on both paintings, evidence suggests, developed in Milan around 1508-13.

Portions of the Salvator Mundi project were likely delegated to senior associates, such as Boltraffio, d’Oggiono and/or Salaì. During this period, Luini and Francesco Melzi (around 1491-1570) also studied Leonardo’s work. Is it possible to see the hand of any Leonardo associates in the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi? Stylistic comparisons indicate that Luini might have worked on it before Leonardo left Milan in 1513. This was an extended project, with two or more versions, lasting months, if not years, due to the multi-layered oil-painting technique. Comparisons with Luini’s work around 1512-20 include paintings in Milan—Saint Anthony of Padua, Christ Blessing, Holy Family with St Anne and St John, Madonna of the Rose Bush, and Madonna with the Child—and Salome with the Head of John the Baptist in Vienna; Suzanna and the Elders at Isola Bella; and, notably, his Christ among the Doctors in the National Gallery, London. Dates for some of Luini’s oil paintings are still in question. Based on stylistic evidence, Christ among the Doctors may date to 1510-1522.

In 1508, Luini moved his studio to Milan and was soon in contact with Leonardo, who was then working for Louis XII. Coincidentally, one of Leonardo’s red chalk grotesque head studies of around 1508 was copied by Luini or an associate. With this drawing is an early sketch for Luini’s Christ among the Doctors. Facial features of both the Abu Dhabi and De Ganay Salvator Mundis compare remarkably well with Luini’s Christ, visible when the faces of the Salvator Mundi and Christ among the Doctors are overlapped.

Luini’s family acquired a St Anne cartoon and 50 red chalk drawings by Leonardo, and Luini’s direct contact with Leonardo’s paintings is noticeable: in both painters’ approaches to precise white heightening (as in the hair and stole in the Salvator Mundi); in the modelling of three-dimensional illusion or rilievo (relief), especially in the drapery; in the richness of colour volume; in the precise treatment and slight imbalance of pictorial elements, which are the details that animate these features with implied movement; and especially in the sfumato (smoky shadow) technique. As noted by Martin Kemp, “of the close followers, only Bernardino Luini came close to the judiciousness and decorum with which Leonardo used sfumato”. Kemp also refers to Leonardo’s “hypernaturalism”, which is also a feature of some of Luini’s best paintings. According to Linda Wolk-Simon, Luini was “arguably the most thoroughly Leonardesque of the leonardeschi”.

The recent authentication of the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi as a Leonardo should lead to a much more thorough assessment of the role of his studio and associates, and Bernardino Luini’s involvement with them. Regardless of the general agreement for or against these attributions, there is now an opportunity in Abu Dhabi for a sustained look at this rare painting, for additional connoisseurship, historical research and technical and scientific analyses. Maybe Bernardino Luini will then step out of the shadows.

• Matthew Landrus is a research fellow at Wolfson College and Faculty of History, University of Oxford. His book, Leonardo da Vinci, is published by Carlton in September (160pp, £25)

Luini’s Presence?

Overlapped false colour scans of Luini’s Christ among the Doctors and the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi (2+1) and the De Ganay Salvator Mundi (2+3) reveal that Christ’s facial features compare well. The overlap of the two Salvator Mundis (3+1) shows that, proportionally, the filigree bands are identical, the crystal balls are similar, and Christ’s right hand is slightly different. The locations of the hands and crystal ball are partially shifted, indicating the use of more than one cartoon.

Matthew Landrus