At Eternity’s Gate, Julian Schnabel’s film on Van Gogh, is due to be premiered at the Venice Film Festival Monday (3 September). The US actor Willem Dafoe plays the Dutch painter. Although dozens of dramatised films have been produced on Van Gogh since Lust for Life in 1956, this latest production is different in that it is directed by an artist.

Schnabel, who focuses on Van Gogh’s final years in France, describes his film as “fiction”—and “about what it is to be an artist”. He says “the only way to describe a work of art is to make a work of art” and what should emerge in his film is “more true than literal fact”.

Willem Dafoe as Vincent van Gogh in Julian Schnabel’s new film At Eternity’s Gate Courtesy of the artist and the 75th Venice International Film Festival

In this week’s blog I want to explore the story of the artwork that provided the title for Schnabel’s film. Although it is the painting of At Eternity’s Gate (Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo) that is now well known, Van Gogh based it on a drawing and a resulting lithograph which were both made eight years earlier.

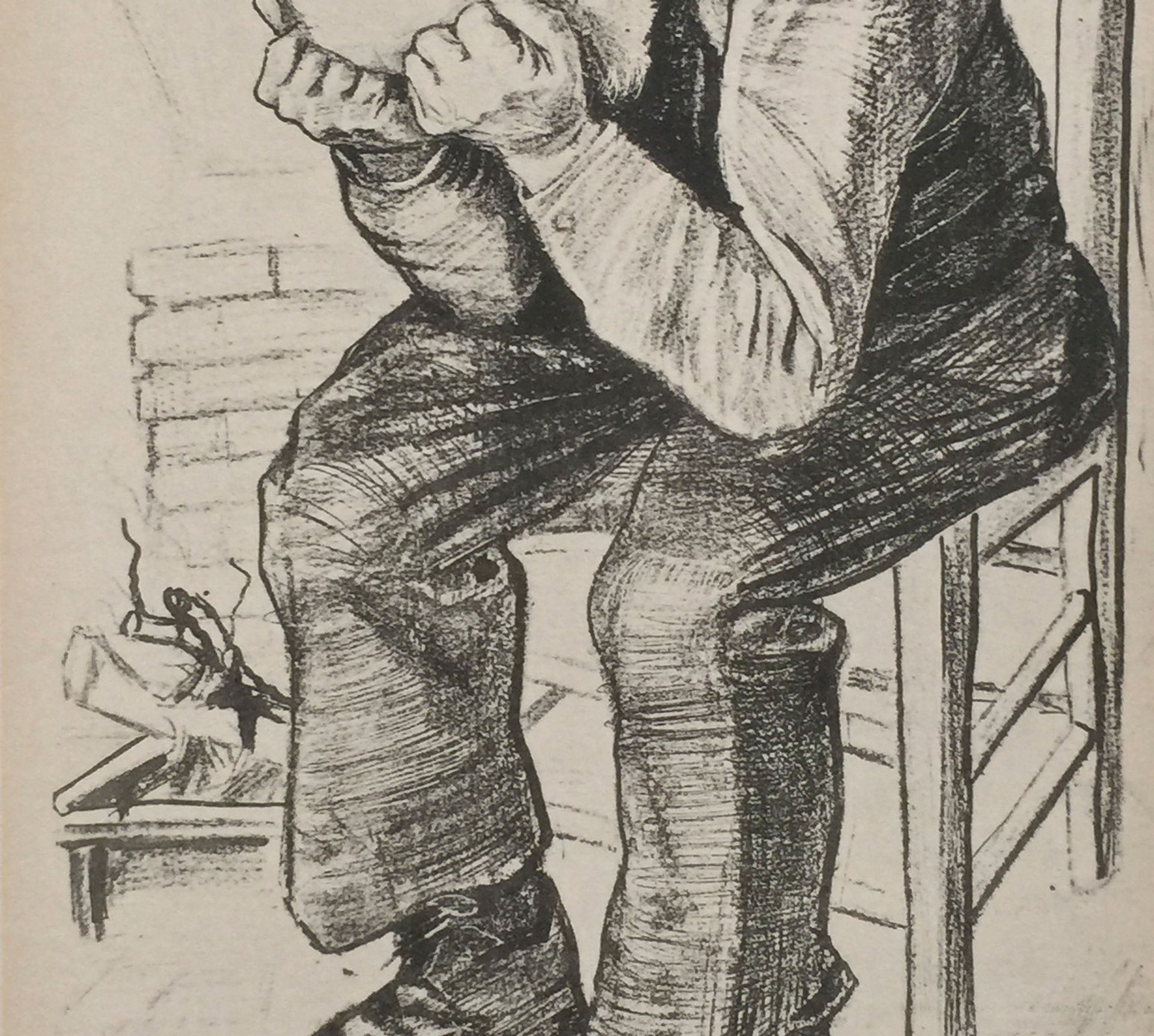

The lithograph, produced in The Hague in 1882, portrays a grieving elderly man sitting with his head in his hands, deep in sorrow. Only seven copies survive, and on one of them the artist inscribed the title in English, “At Eternity’s Gate”.

Van Gogh, At Eternity’s Gate (lithograph), April 1882

The English inscription must have been added because Van Gogh was intending to send the print to the Illustrated London News or the Graphic, to solicit work. He never seems to have actually posted the lithograph and it is hard to imagine an editor in London wishing to publish the work of this unknown Dutchman.

The copy of the lithograph with the English title later ended up in a rather unexpected place: Iran. In 1975 the Shah’s wife, empress Farah Pahlavi, was assembling a collection of modern art and bought the print from the New York dealer Eugene Thaw. After the Shah was toppled, four years later, her pictures were stored in the vaults of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. Although the museum reopened many years later, Iran’s sole Van Gogh work has rarely been exhibited.

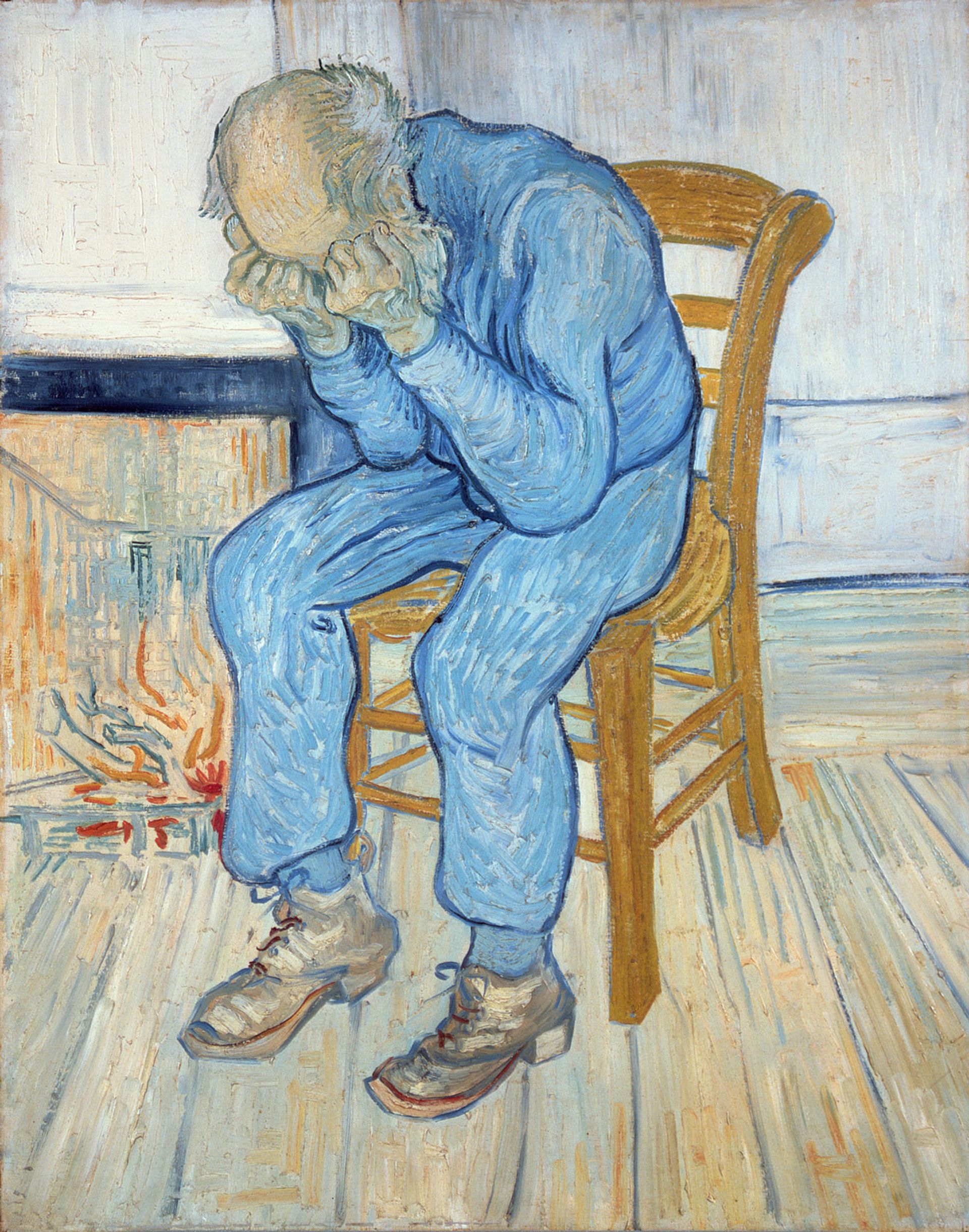

But let’s move back to Van Gogh’s time. In April 1890, when Vincent was at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, he asked his brother Theo to send him some of his early works on paper from his Dutch period. The drawing or print of At Eternity’s Gate was presumably among those dispatched, since a few days later Vincent used it as the basis for a painting—enlarging the composition, making minor modifications and transforming it into colour, using one of his favourite blues for the man’s clothing.

Van Gogh, At Eternity’s Gate (painting), May 1890 © Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

In my new book, Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum, I suggest that when making the painting, the artist may have partly had in mind one of his fellow patients. Thanks to a newly discovered register it is now possible to identify most of Van Gogh’s 18 “companions in misfortune”, as he called the other men. The title of the painting suggests that the man is approaching death, and at the asylum there were two patients aged 77, a venerable age for the time: Antoine Silmain, a retired priest, and Jean Biscolly. Seeing one of them sitting in the common room may have sparked off his decision to translate his earlier black-and-white print into colour.

But there is a further dimension to the story. The clenched fists of the seated man may also suggest the anguish that Van Gogh himself had so recently faced. In February 1890, the artist had a relapse of his mental problem. He suffered terribly for a couple of months. Two weeks before starting the painting, his doctor Théophile Peyron, had written to Theo reporting that his patient “usually sits with his head in his hands, and if someone speaks to him, it is as though it hurts him, and he gestures for them to leave him alone”.

A fortnight after the doctor’s letter, Van Gogh was back at his easel, completing this expressionist masterpiece. At Eternity’s Gate represents something of a self-portrait—not in physiognomy, but in posture. We await to see how Schnabel captures and interprets Van Gogh’s life in the asylum.

• For more on Saint-Paul-de-Mausole see Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum, published by White Lion (available through Amazon in the UK and US)

• For more on Julian Schnabel's film At Eternity Gate see the Venice Film Festival website