Although Sol LeWitt died in 2007, his wall drawings have lived on, in the shape of new installations created by draughtsmen and women following the artist’s written directions. The perpetual re-creation of these conceptual works makes cataloguing them a complicated process, which LeWitt himself oversaw in three printed books published in the 1980s and 1990s. This summer, the digital firm Artifex Press published an online catalogue raisonné of LeWitt’s wall drawings; started during his lifetime and completed in collaboration with the artist’s estate, it allows for new research to be added via an upload.

As with any research project, new discoveries have been made, including 32 previously unrecorded works, often variations of known wall drawings, which have now been assigned official numbers by the artist’s estate. The door remains open for more works to be identified, however. “There are some [where] we don’t have enough evidence to confirm the first installation of a work. Sol was always coming up with ideas; there were concepts, plans in the documentation [we’ve looked through],” says Lindsay Aveilhé, the catalogue’s editor. “But it wasn’t a wall drawing unless it was installed. So, there are things here and there that could be something, but we don’t have enough to assign them a traditional number.”

“Now that the catalogue is published, it could [encourage] more [people with] information to come forward,” Aveilhé adds. “We’re open to the possibility of pinning down works in the future, although then the problem of [finding] evidence comes through.”

LeWitt created his first wall drawing in 1968, for the opening of Paula Cooper’s gallery in SoHo, New York. Based on simple instructions, which often serve as part of the title, and diagrams made by the artist, the works are created directly on the surface of a wall using basic materials such as pencil, ink wash, crayon and string. “Neither lines nor words are ideas; they are the means by which ideas are conveyed,” LeWitt wrote in his 1971 essay Doing Wall Drawings, which might be the simplest encapsulation of the concept behind them.

There are now around 1,350 of these works—some realised for the first time after the artist’s death, and a couple that are yet to be physically created—and they have been installed more than 3,500 times at more than 1,200 different venues, with new installations added to the list all the time. LeWitt worked on documenting and categorising his wall drawings throughout his career, refining the numbering system for all the works and variations in 2006, the year before he died. But he was also known to improvise on site and make changes to colours or orientations based on his reaction to the architecture. Consequently, cataloguing the wall drawings—like the pieces themselves—has been a constant work in progress.

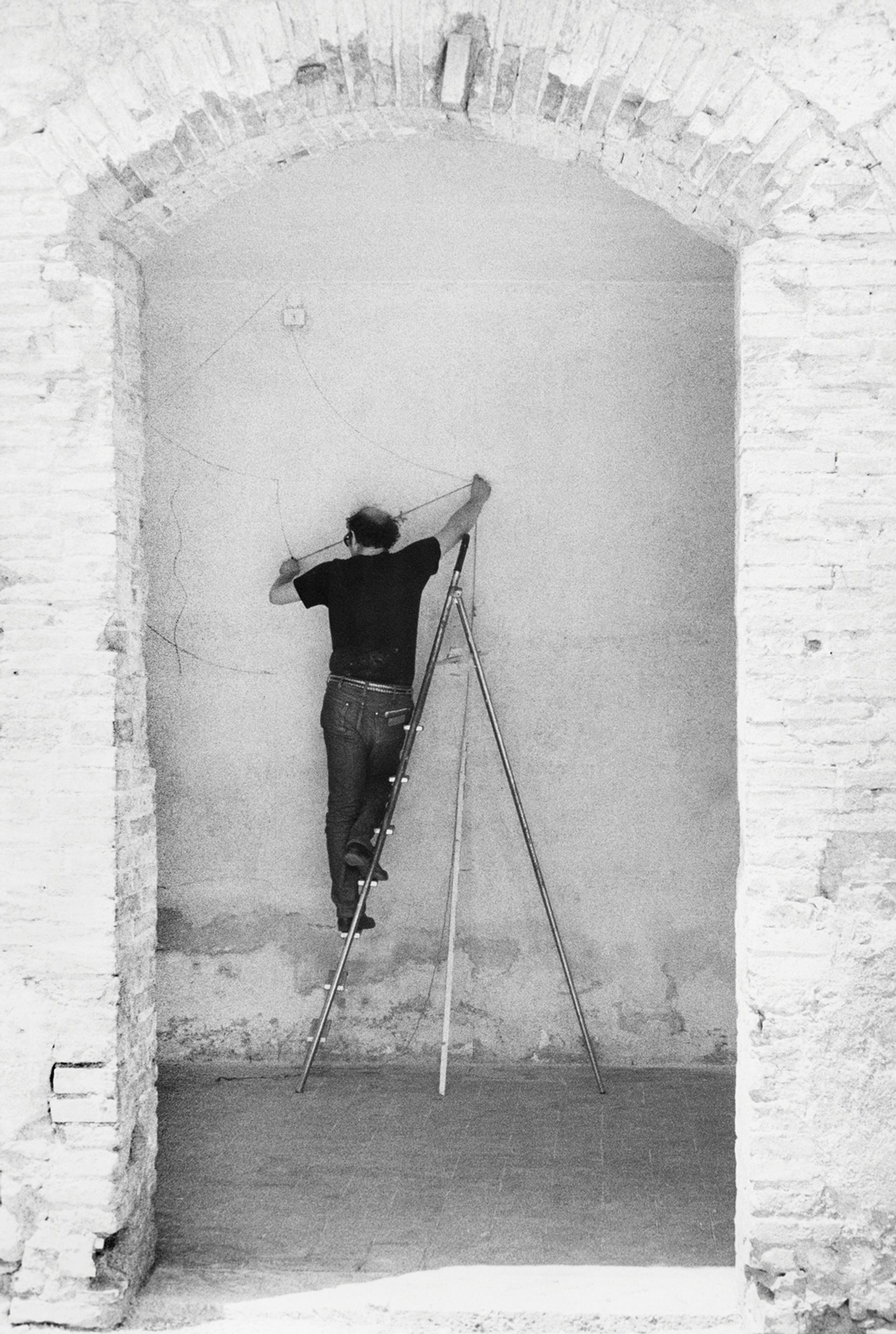

There were around 1,350 designs by LeWitt (pictured here in Italy in 1972) Photo: Giorgio Lucarini; © Estate of Sol LeWitt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy of the Estate of Sol LeWitt

“One of the initial ideas behind doing these catalogues digitally was that you can correct and update the information [easily],” says David Grosz, the editor-in-chief of Artifex Press. “You can’t do that in book form.”

Sol LeWitt Wall Drawings is the seventh catalogue that Artifex has published, and there are more in the works. Organisations like museums and galleries can either pay an annual subscription to access all the catalogues available, for a fee depending on the type and size of the institution, or buy individual publications for $300 to $500 and pay an annual $50 maintenance fee. In comparison, the five-volume catalogue raisonné of Andy Warhol’s paintings and sculpture, published by Phaidon, which covers around 3,000 works from 1961 to 1978 (and is still not finished), is currently priced at around $2,000.

But more than ease or costs, what makes the digital format ideal for the catalogue raisonné, Grosz says, is its ability to draw connections. “With a book, you’re essentially looking at the list of works; there’s an index. A decision is made about how to order the catalogue, and there’s one way to look at it: front to back,” he says. “A database is a much richer format. With the digital catalogue, there are a number of different entry points.” Works in the catalogue are grouped by time period, materials and LeWitt’s idiosyncratic names for series, such as Arcs & Lines and Loopy Doopy; they can also be searched by keywords such as location and collection. “At its heart, a catalogue raisonné is a list of works,” Grosz says, “but we’re able to take any of the associated metadata and generate relationships.”