Few experiences are more gratifying than seeing a complex, rarely explored artist presented with the freshness, polish, and insight of the Whitney’s retrospective of the artist David Wojnarowicz (1954-92). Difficult to define and certainly impossible to categorise, Wojnarowicz is far more than a rage machine aimed at homophobia and the Aids epidemic that killed him. The show discovers the qualities that make his work universal and meaningful in any age where hate, fear, and ignorance jostle with understanding and acceptance.

There is no trajectory in Wojnarowicz’s work. He was ravenously curious and moved freely among media. As an uncredentialled, self-educated outsider, he did not value boundaries. He is the wild card of his age but the 1980s was a wild time where outsiders became canonical, disciplines melted and mixed, and American art first became a hydra with infinite heads.

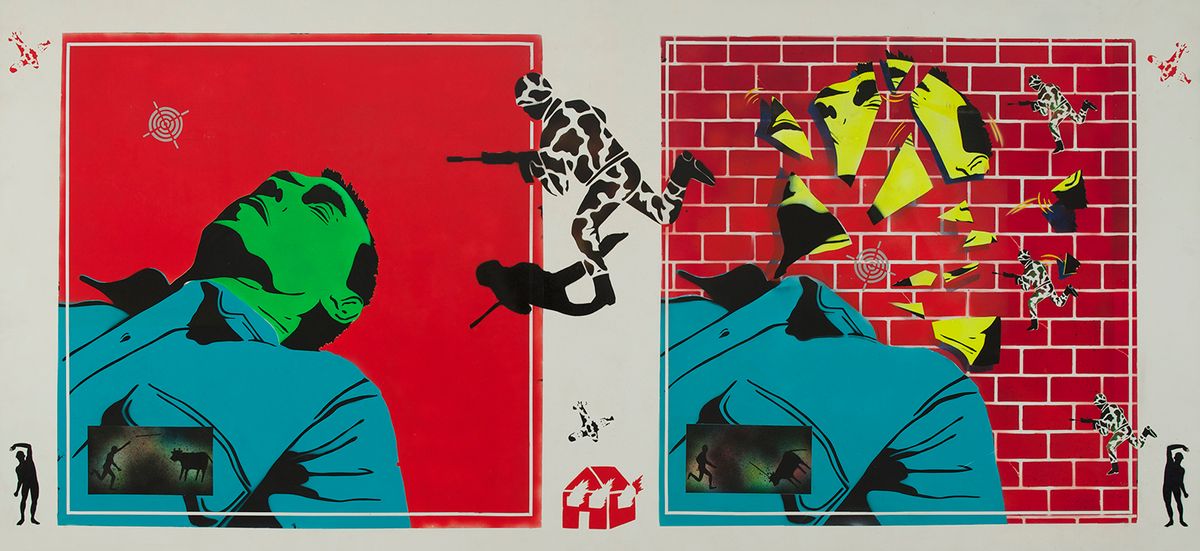

There is little juvenilia to drawn from, either. Wojnarowicz had a taste for the primitive and his early work—mostly graffiti art, sculpture based on found objects, and weird, totemic plaster busts—shows a vision that stayed experimental and unique. He was always entrepreneurial. As a young man, he had no money and was often homeless but still made art. As a street hustler, he experienced lust at its kinkiest but also its most desperate and dangerous. His upbringing was chaotic and unpleasantly nomadic, his parents unstable and mean-spirited. He was, and the gorgeous gallery of his early work shows this, “willfully feral”. It is an apt phrase from the unusually good catalogue. It stresses iconography, social history, connoisseurship, and formalism but is also deeply biographical. Wojnarowicz’s voice and presence are never far, in the show or the book.

David Wojnarowicz, Arthur Rimbaud in New York (1978-79, printed 1990) Collection of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992); courtesy P.P.O.W, New York. Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

If there is a youthful presence in the exhibition, it comes via Wojnarowicz’s fascination with the French poet Arthur Rimbaud. I always thought the artist’s early series of photographs of friends wandering the city wearing Rimbaud face masks was one-dimensional, even contrived and silly. Understanding more about Wojnarowicz’s attraction to Rimbaud gave me context for the work. Rimbaud, and I suppose Wojnarowicz, felt that a “scummy”, or self-abased lifestyle, was essential to becoming a poet and, later, what Rimbaud called a “seer”. The poet, in Rimbaud's words, experiences “every form of love, of suffering, of madness... he consumes all poisons in him, and keeps only their quintessence”. He then arrives at the unknown, becoming its medium and a prophet.

Rimbaud, Jean Genet, William R. Burroughs, and Walt Whitman were all important figures for Wojnarowicz. The show has the right balance between acknowledging these writers but also revealing what Wojnarowicz saw in them and how he amalgamated what he learned into something new and distinctive. Wickedness, wanderlust, pathos, and yearning for love are constant themes. Wojnarowicz is always edgy but with a touch of the Victorian.

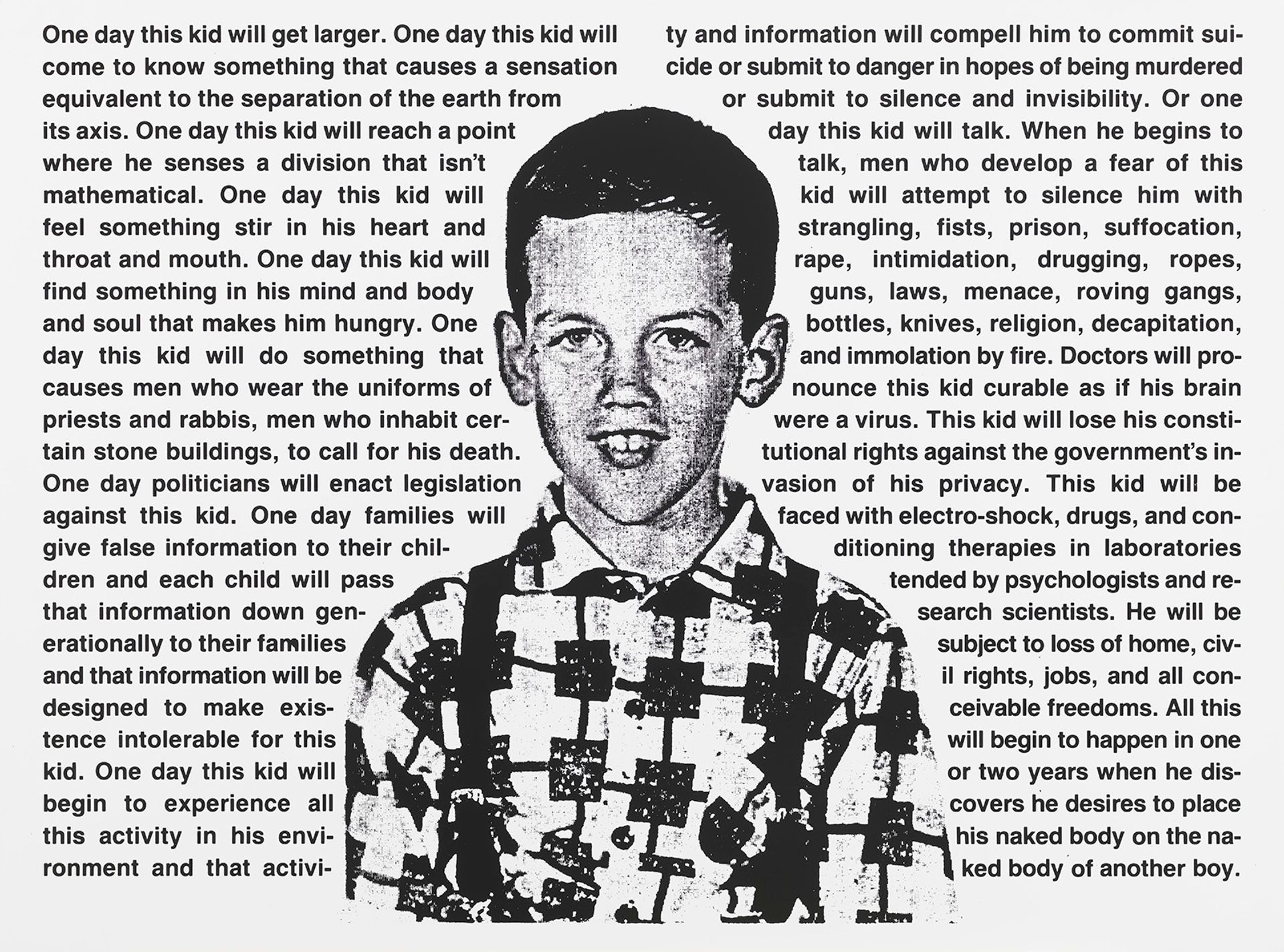

The work Untitled (Face in Dirt) (1992-93), made the year he died, is a most unusual self-portrait. It is also a landscape, and a new twist on the Old Master vanitas genre. Untitled (One Day This Kid) (1990-91), is narrowly about the many stigmas gay people face but, more broadly, about self-discovery, individuality, and the essential weirdness of everyone. It is a good access point to Wojnarowicz’s writing, which at its best is beautifully sculpted and very stream-of-consciousness.

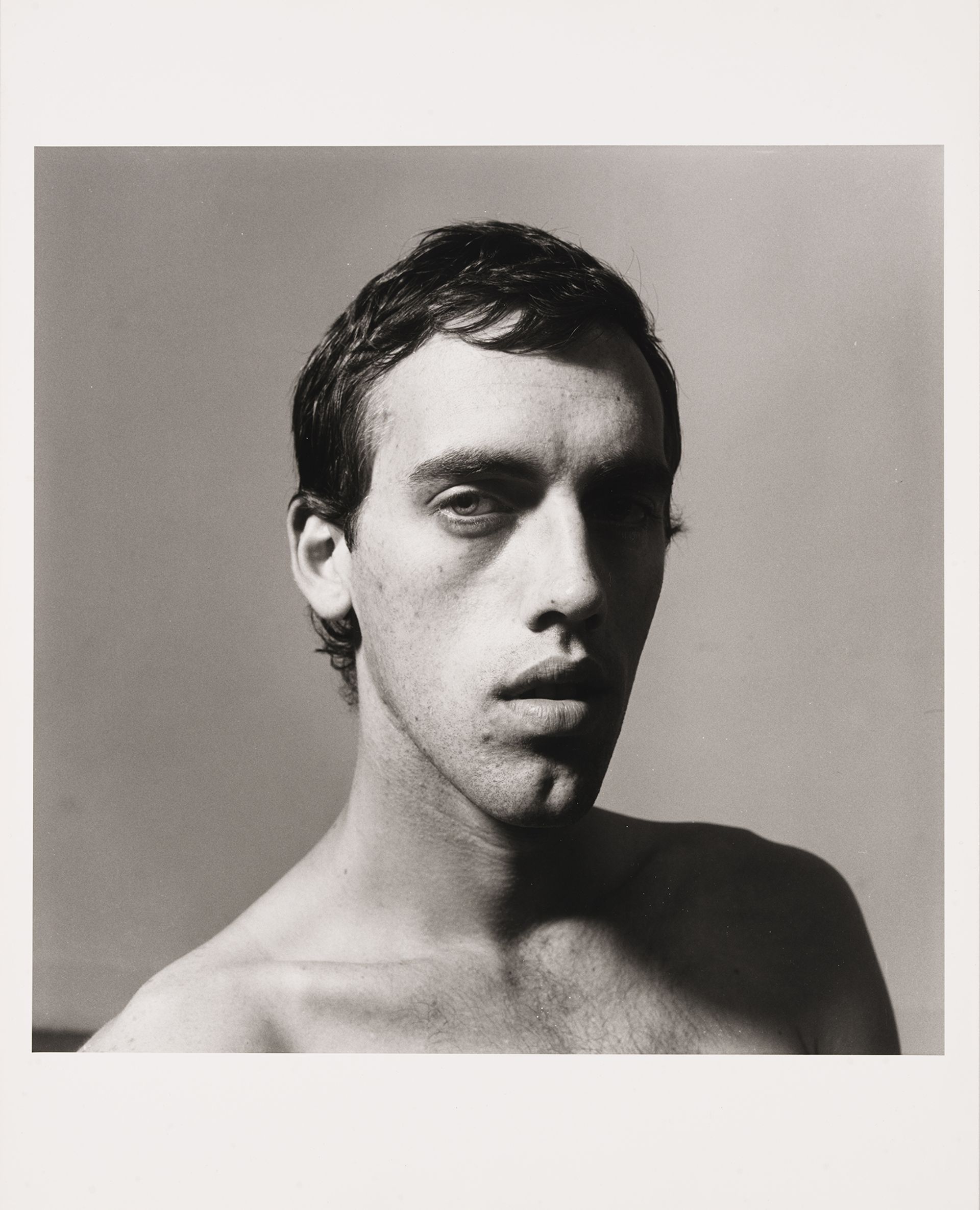

Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz (1981) Whitney Museum of American Art; purchase with funds from the Photography Committee 93.76

The show also treats Wojnarowicz’s relationship with Peter Hujar (1934-87) with care and empathy. They were boyfriends for a time but Hujar grew to be, as Wojnarowicz said: “my brother, my father, my emotional link to the world.” Hujar convinced him he was an artist and encouraged him to paint. He was a mentor and ballast, but it has to be said Wojnarowicz was already an incredibly strong person. A lesser man would have been long ago crushed. Hujar’s photographs of Wojnarowicz are sexy and romantic, with a film noir sultriness. Minutes after Hujar died of Aids, Wojnarowicz filmed and photographed his head, hands, and feet. The works are tough to look at, as tender and honest as they are.

Wojnarowicz is best described as visceral. He used ants as subjects in part because they live in the dirt. On the one hand, they are tiny and defenceless against most predators. On the other, they see things close up. They can reach hidden places. They experience a world obscure from those looking from loftier heights. Wojnarowicz developed deep, loving connections with other men. He was amazingly productive. Yet he lived much of his life, until he was about 30, in the gutter.

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (One day this kid . . .) (1990-91) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Print Committee 2002.183. Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

He seems consumed by rage, and rage gets tiresome fast. I say “seems” because looks are deceiving, as the show deftly proves. The very good artist Zoe Leonard once showed Wojnarowicz her prints depicting clouds. She felt they were subtle and abstract, so beautiful they were useless at a time when there was so much to protest. Wojnarowicz told her: “Don’t ever give up on beauty.” He kept his eye on the target. Everything he did and thought was intended to bust the barriers and prejudices keeping outsiders like him from savouring life’s beauties. He saw himself, after all, as a survivor.

• David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, until 30 September