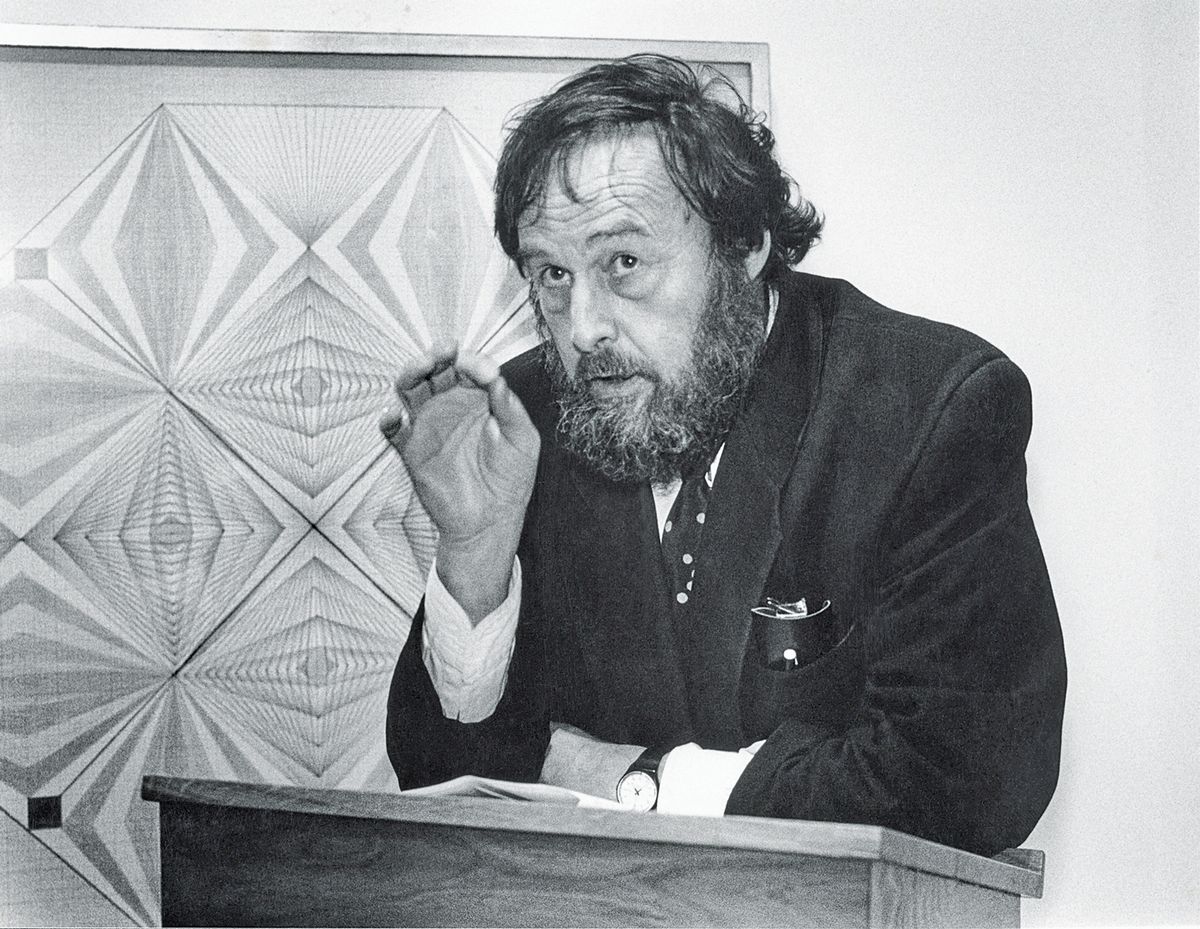

With his beard sometimes longer, sometimes a little shorter, his hair always medium-length with a strand falling over his face—that was how we knew Harald Szeemann, the inventor of the profession of “curator”. We can still hear his booming voice, with the dark, guttural tones of his Swiss dialect; we can see him in our mind’s eye, in a white, collarless shirt and dark waistcoat. This is how he would welcome visitors to his Swiss refuge; it was particularly surprising that this archetypal “man of the world” chose to prepare his exhibitions and dip into the unfathomable depths of his archive in, of all places, the legendary Fabbrica Rosa in Maggia, above Locarno, Switzerland, equally far from Zurich and Milan airports.

Szeemann collected anything he could lay his hands on, from cases of wine (he also documented his wine consumption), which were used afterwards, very practically, to store smaller papers and brochures, to the airline luggage labels used before the rise of digitisation, still made of coloured card printed with three letter references to airports.

The importance of Szeemann is shown by the fact that the Getty Research Institute was willing to buy his archive: not only will it be preserved for future generations, but the centre paid a considerable sum to secure purchase of this valuable treasure. There are documents filling 750m of shelving, as well as 26,000 books. Anyone with the same collecting bug will understand why Szeemann needed an empty factory building, not just to store all of this, but also as an office for his Agency for Spiritual Guest Work.

Szeemann, born in 1933 in Bern, was appointed director of the Kunsthalle Bern at the age of 27. From the very outset he aimed to create something radically new, first in art and then in the way in which it was displayed. Several of his exhibitions have made art history, beginning with the Wrapped Kunsthalle (1967), Christo’s very first major project. In 1969, the exhibition When Attitudes Become Form paved the way for US conceptual art in Europe and upset the Kunsthalle Bern trustees. He resigned and rom then on, Szeemann was a free man – and in 1972 he organised documenta 5 as a total work of art. Szeemann happily tore down the traditional boundaries between art and everything else. He even asked the Chinese, under Chairman Mao, to provide some Socialist Realist art. They did not, but it demonstrated his spot-on instinct for future developments.

Szeemann was now a member of the exclusive group of curators in demand worldwide, such as Pontus Hultén, Germano Celant and Kasper König. He was in a position to choose his own exhibition projects. He was either solely or largely responsible for more than 150 exhibitions. When he was not working on a commission – for which he charged considerable sums – most of his time was spent on one project. This was the “Museum of Obsessions”, a “parody of the conventional museum with its established value systems and unmanageable bureaucracy”, as Doris Chon from the Getty Research Institute writes in her contribution to the book. Szeemann himself had in mind a place where “new connections could be tried out”. He showed how this obsessive arts-related activity had come about in his 1983-84 monumental travelling exhibition Tendency Toward the Gesamtkunstwerk: European Utopias since 1800.

In all his important exhibitions, Szeemann essentially engaged with the myth of the artistic genius as an outsider on the margins of society, or, taking the idea further, with the myth of the outsider as the truly creative figure. He always chose to focus on eccentrics and failures: in his view, the artist is only a pale imitation of a man possessed—the latter is the real genius. Museums he saw as merely the final resting places of grand visions, all of which belonged outside the bounds of society. Szeemann himself admittedly made a very good living from this image, this projected desire. His death, early in 2005, was sudden and too soon: he seemed to have dozens of exhibitions still in him.

The articles in the book are initial attempts to reflect the vast scale of the archive so suddenly left behind. None of them attempts to summarise Szeemann’s way of working. Some information on this can be gleaned from the essay by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, one of Szeemann’s (failed) successors in the documenta hot seat. Her essay states matter-of-factly that Szeemann, “on the run from demands from the city of Kassel after he exceeded the documenta budget”, found “protection in the safe haven” of Ticino.

The reader searches the book in vain, however, for a chronological list of Szeemann’s exhibitions, or for a bibliography. Such a bibliography would have shown that a catalogue of all Szeemann’s exhibitions was already published as early as 2007. This important information, however, can only be found in the essay by Beatrice von Bismarck. Otherwise, the book’s 406 large-format pages contain many photographs from the Szeemann estate, accompanied by interviews with friends and artists. The photographs conjure up nostalgia in those who were able to see one or even several of Szeemann’s large exhibitions and have vivid memories of these. For a younger generation of readers, however, much of this will come across as strange and obscure.

The book itself is obscure from the very beginning. The photograph that follows page viii and the foreword by Thomas Gaehtgens, director of the Getty Research Institute, has no caption: anyone who does not know that this is a picture of Plight, the famous Joseph Beuys exhibition held in autumn 1985 in London’s Anthony d’Offay Gallery, would wonder what the link was to Szeemann. Only later does the reader learn that it was because the Kunsthalle Bern trustees turned down the idea of a Beuys exhibition that Szeemann resigned as director in 1969 and thereafter never returned to a fixed post. A quarter of a century went by before Szeemann was able to organise a Beuys retrospective, in 1994, at the Kunsthaus Zurich; Szeemann had been loosely connected with this institution since 1981, as a “permanent freelance”, as he wished to have his job described. In Zurich, Szeemann was able to reconstruct the Plight installation, as the reader has to deduce from the hidden picture caption, set out in small print on the inner cover.

Szeemann’s work was always characterised by these sorts of underlying references. Work on his archive is only just beginning, and it will therefore be up to a future publication to move away from the admiring attitude largely taken by this book towards one which involves a certain amount of critical distance.

• Bernhard Schulz is the art critic of Der Tagesspiegel, Berlin. His main interest is in the German and Soviet politics of art and culture in the first half of 20th century

Glenn Phillips and Philipp Kaiser, eds., Harald Szeemann. Museum der Obsessionen (Museum of Obsessions), Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess, 406pp, €68 (hb); Getty Publications, 416pp, $69.95 (hb)