After celebrating “Capability” Brown’s tercentenary so thoroughly in 2016, it seems appropriate to look at gardens made before his time, places that he is often accused of having wiped from the face of England when creating his landscape parks. Anyone who has seen Peter Greenaway’s 1982 film, The Draughtsman’s Contract, will think they have a good idea of what gardens looked like before Brown got to work. They had long straight paths between high hedges, with people in preposterous wigs plotting sinister deeds beside equally long and straight canals. Luckily, in Gardens of Court and Country, David Jacques offers a more nuanced view, showing how gardens changed over a century from 1630 to 1730 and how foreign models—French, Italian, Dutch—were adapted to suit English terrain, taste and climate.

What his rich text presents is a host of quite extraordinary gardens, most of them barely on the radar of garden-lovers today because hardly any have survived. Many, particularly those close to big cities, such as Cannons in Middlesex, lie buried under suburban housing; others, like Hampton Court, were changed by successive owners responding to fashion or reluctant to pay for the intensive clipping and mowing such places require.

This was the period that saw the rise of the professional gardener—George London and Henry Wise, Charles Bridgeman, Batty Langley—men who were nurserymen, designers and contractors capable of organising the massive moving of earth and trees their creations involved. Yet garden-making was not a totally separate profession and one of the interesting background facts revealed by Jacques is the deep involvement of many owners, from royalty down to the squirearchy, most of whom also had demanding day jobs—fighting wars, running the country’s economy, writing plays and poetry. Christopher Wren, John Vanbrugh, John Evelyn and Alexander Pope are just four examples of men famous in other fields who were also involved in garden design.

Jacques deals with his subject chronologically and by the second half of the book it is interesting to note how many of the elements we see as “Brownian” or even Picturesque are already beginning to appear—ha-has, cascades, obelisks, temples, meandering paths, clumps of trees planted to emphasise the natural contours of the land. The circular or octagonal “basons” of the early years become lakes with irregular edges and George I orders six fishponds in Kensington Gardens to be joined up to form the lake we now know as The Serpentine. As early as the mid-17th century, gardens began to look outwards towards the countryside, with brick walls gradually replaced by ironwork that allowed a view through, and then the boundary disappears altogether and becomes the ha-ha—changes possible only once the fear of civil war and invasion had receded.

Politics was a far greater influence on the creation of gardens than we can easily appreciate today. When the Whigs were in power, their grandees made gardens, to be succeeded later by Tories, with each complaining about the extravagance of their predecessors. Jacques comments on how Protestantism, indeed Puritanism (and not only during Cromwell’s Commonwealth) affected garden fashion, so that English gardens were always less ornamented than their French counterparts—less “broderie”, for instance, and more plain lawn.

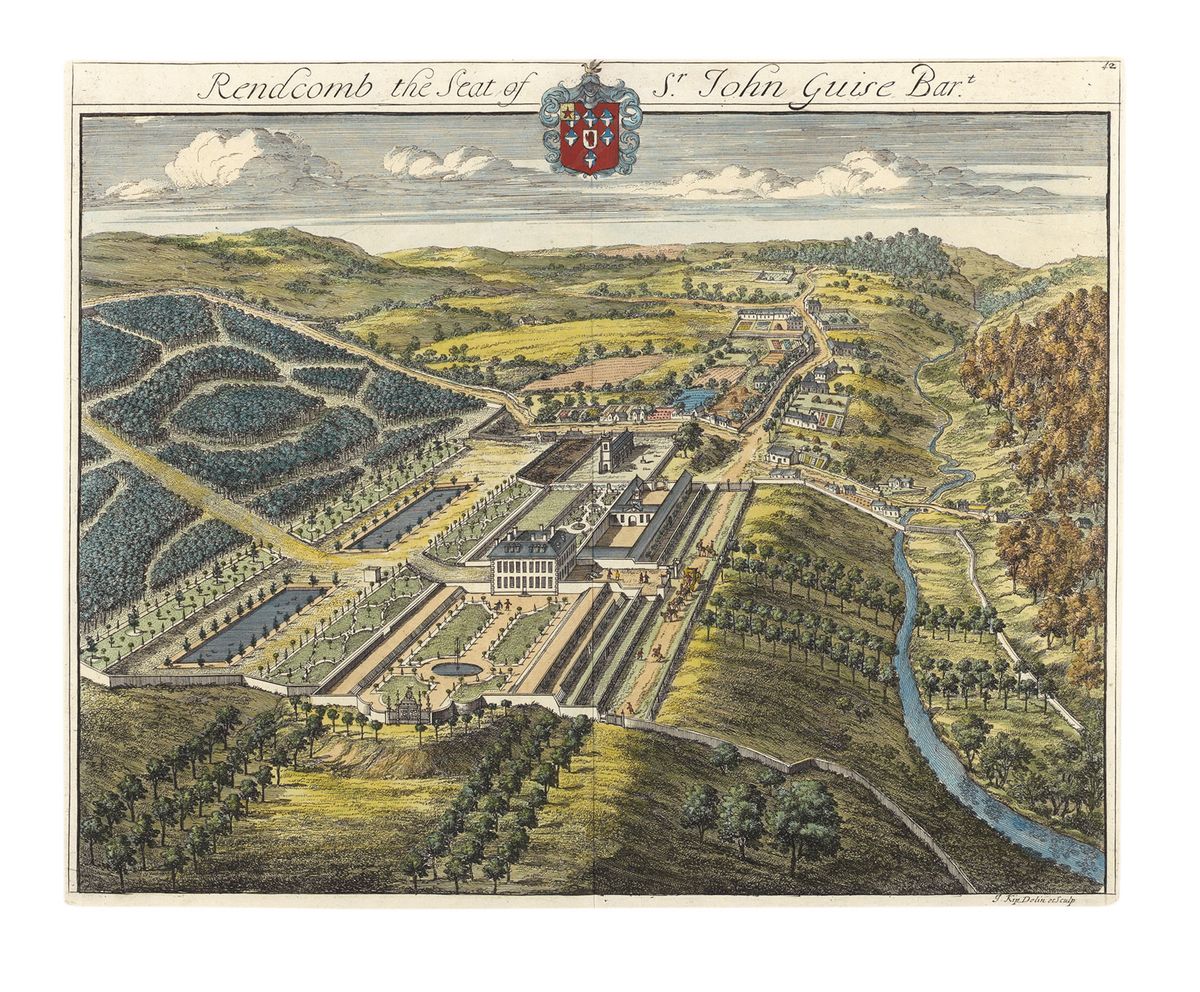

Given how few of these gardens are there to be seen today, Jacques has to reply on less ephemeral evidence about their creation. Written sources include estate accounts, letters, the new genre of travel writing both by professionals, such as Daniel Defoe, and amateurs, like Celia Fiennes, and diaries, particularly those of Evelyn, a man deeply interested in all aspects of gardening and himself an international expert on trees. There were also books, many of the most influential being translations from the French. Pictorial sources include plans, surveys and maps, like those of John Rocque, paintings and, above all, engravings. One thing The Draughtsman’s Contract really got right is the idea of an artist being paid by an owner to depict his garden and so publicise its glories and his family’s status. The paintings of Leonard Knyff, and particularly the engravings made of them by Johannes Kip, not only provide important evidence for today’s historians, but were the chief source of diffusion of fashionable ideas.

The illustrations are beautifully reproduced—a triumph given that some of the original archive images must have been of poor quality—and the captions are informative essays in themselves. But the endless plans and bird’s-eye views become slightly monotonous and one would have been glad of more portraits of the people involved. (There are only two, of Wise and of Bridgeman.)

I would also have welcomed more photographs of how the sites look today. Indeed, my main criticism of this book is that Jacques, so meticulous in detailing the creation of these gardens and imaginative in his analysis of what can be deduced from plans and engravings, seems so little interested in what became of such extraordinary places.

There is an interesting postscript on gardens in Virginia and South Carolina made by settlers influenced by these English gardens, but it would have been useful to include a gazetteer of what might still be seen in England today. Chiswick House, Hampton Court and Kensington Gardens are well covered, but the restored garden at Kirby Hall is given little space and, strangely, St Paul’s Walden Bury, in Hertfordshire, which can be dated to 1730 and is perhaps the most intact garden of this period, is not mentioned at all.

• Gillian Mawrey is the chairman of the Historic Gardens Foundation and the founding editor of its journal, Historic Gardens Review. She is the co-author of award-winning The Gardens of English Heritage (Frances Lincoln) and is currently working on a book about the Loire Valley

David Jacques, Gardens of Court and Country: English Design 1630-1730, Yale University Press, 416pp, £45 (hb)