An estimate last month to restore Ilya Repin’s painting Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on November 16, 1581 (1885), damaged by a metal-pole-wielding assailant at Moscow’s State Tretyakov Gallery, was Rb30m ($474,000). This is 60 times the sum reported immediately after the incident on 25 May. Reports on social media speculate that the wild disparity between the original estimate of Rb500,000 ($7,900) and the new figure, both revealed by the law enforcement officials, may be a way for the prosecutor to pursue a longer prison sentence for the vandal. But a Tretyakov spokeswoman says the figures “bear no relation to the real sums” and that the museum is working on a detailed report.

Igor Podporin, the man Russian authorities have charged with the attack, recanted an earlier confession that blamed his actions on being drunk. While still admitting he was behind the attack, he now says he targeted the painting because it “offends the feelings of religious believers, of [the] Orthodox [church], and in general, everyone in Russia”, as stated at his court hearing. The painting depicts Ivan the Terrible cradling his son after murdering him in 1581—a version of history now disputed by those seeking to rehabilitate the notorious Russian tsar’s image.

A spokeswoman for the Tretyakov told The Art Newspaper on 15 June that the treatment of one of Russia’s most famous paintings “had not yet begun” because research was needed “in order to work out a plan and methods of restoration”. The state-owned bank Sberbank will sponsor the repair work.

Andrei Golubeiko, who is responsible for oil-painting restoration at the Tretyakov, described the picture as ‘chronically ill’

Following the attack, restorers arrived immediately to assess the damage to the work, which had been displayed beneath custom-made anti-reflective glass since 1996. At a briefing on 28 May, the museum’s director Zelfira Tregulova said the museum is considering paying for additional security out of its own funds because the government cut back museum guard posts in 2015.

The picture was struck by a security barrier that tore the canvas in three places and damaged the frame. The faces and hands of both Ivan and his son were, amazingly, unscathed. The faces were restored after a previous attack in 1913 by a mentally-ill icon painter. More recently, the work had undergone close examination over several months in preparation for a Repin survey scheduled for 2019.

A detail of damage sustained by Repin’s Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan (1885) Tretyakov press service

Andrei Golubeiko, who is responsible for oil-painting restoration at the Tretyakov, described the picture as “chronically ill”. Aside from the two attacks, it sustained damage after leaks in the museum in 1922. The piece was purchased in 1885 by Pavel Tretyakov, the collector and philanthropist who founded the museum.

“Our task now is to work out a method for eliminating not only the gash, but [other issues], so that it does not require additional [conservation] in the future,” Golubeiko says. “It’s likely that [specialised equipment] and the help of a large number of specialists will be required.” Tregulova says the Tretyakov would be convening “all the top painting restorers”. The State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg has already offered its help, with its director Mikhail Piotrovsky describing the act “not as an attack on property [but] on a sacred object”.

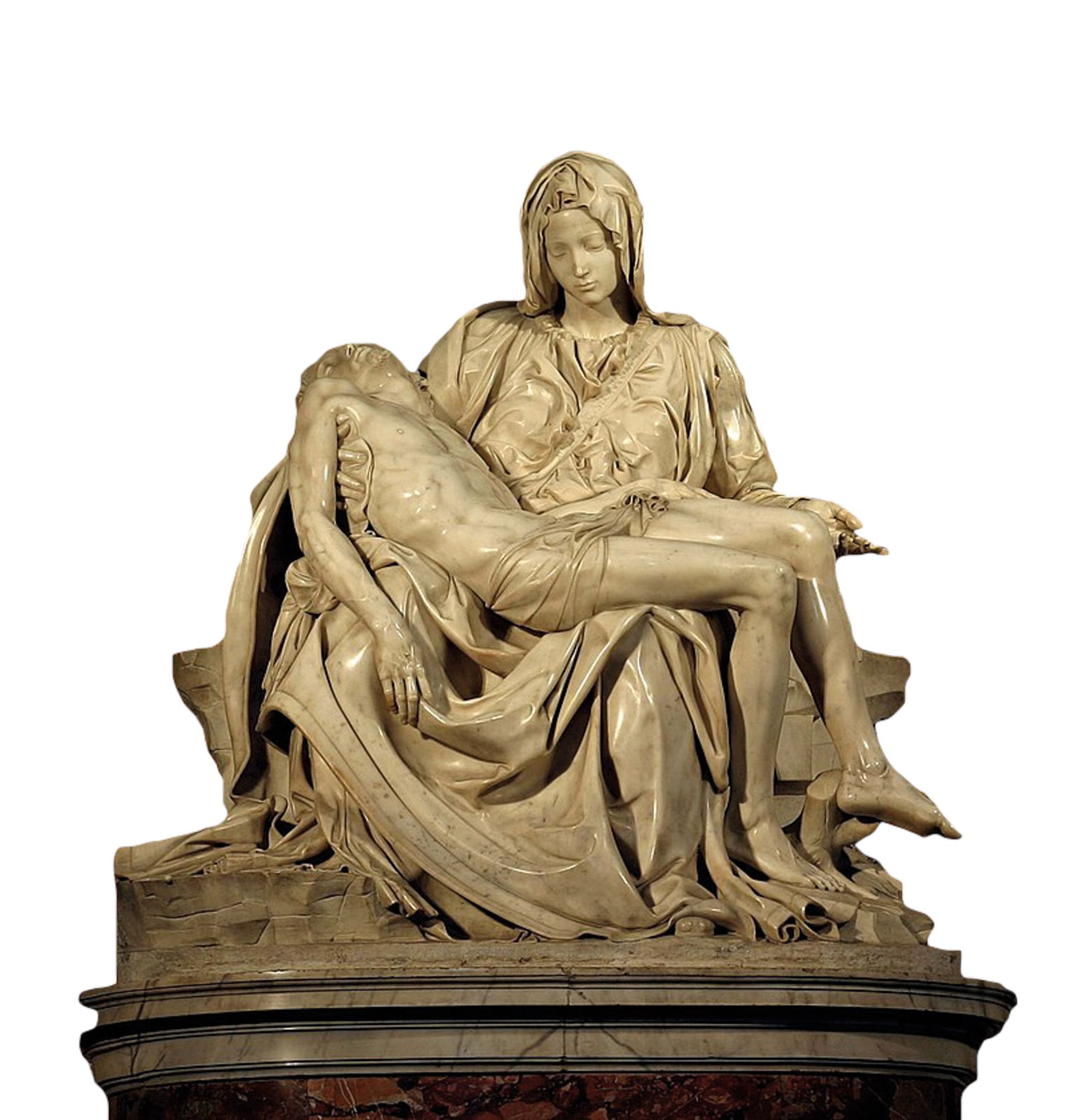

Today’s visitors do not necessarily understand the work’s symbolism: it was painted after the assassination of Alexander II. Repin referenced other Western compositions such as Michelangelo’s Pietà that depict the murder and mourning of a son, in this case Russia’s son. “The [type of] visitor has changed,” says Tatyana Gorodkova, the Tretyakov’s head curator. “Our public does not have a sense of veneration… the lines have become blurred between a social space and a museum space.” She says the museum is considering how to restore the museum’s position as a “sacred space”.

Tregulova warns that society must recognise that the attack “is the beginning of a frightening process” indicative of a disturbing level of aggression that “[society] must condemn as it does terrorism.”

Other notable works to suffer indignities

Michelangelo's Pietà

Michelangelo, Pietà (around 1498)

In 1972, a mentally-ill man struck the Renaissance marble sculpture 12 times with a hammer, damaging the Virgin Mary’s face, arm and fingers, while shouting he was Jesus Christ.

Leonardo, Mona Lisa (around 1503-19)

Vandals have targeted the Louvre’s star attraction several times. Leonardo’s masterpiece has had acid thrown on it and a rock lobbed at it, both of which caused various degrees of damage. Since it’s been behind protective glass, the picture has endured being spray painted and having a tea cup hurled at it.

Rembrandt, Danaë (1636)

Rembrant’s painting finally went back on display at the Hermitage in St Petersburg in 1997—12 years after it was attacked by a man who slashed and threw acid on a nude Danaë. The man had explosives strapped to himself and planned to blow up the painting and himself.

Rembrandt, Night Watch (1642)

The Night Watch in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has also been targeted more than once. In 1911 and 1975 it was attacked with a knife—only the latter of which caused any serious damage. In 1990, quick-thinking guards poured water on the painting after a man threw acid on it, preventing the substance from penetrating beneath the varnish layer.

Velázquez, Rokeby Venus (1647-51)

“I got five lovely shots in,” the suffragette Mary Richardson, also known as “Slasher Mary”, recalled in a 1961 interview. She was referring to an incident in 1914 when she entered London’s National Gallery and slashed Velázquez’s painting with a meat cleaver in protest against the arrest of fellow suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst.

Elías García Martínez, Ecco Homo (around 1930)

Although the intentions of the grandmother who carried out the botched restoration of the fresco of Jesus from a church in Borja, Spain were good, her handiwork caused considerable damage.