Although often overshadowed by the clamour over contemporary art, Old Masters are having a pop culture moment, with the Spice-Girl-turned-fashion-designer Victoria Beckham pronouncing a new-found love of Old Masters, and Beyoncé and Jay-Z filming their new music video in the Louvre.

Such interest is timely for London Art Week (until 6 July), with around 40 galleries and three auction houses exhibiting—and hopefully selling—all manner of “pre-contemporary” sculpture, paintings and works on paper around Mayfair and St James’s.

Dwindling supply is the bane of the Old Master world, and so re-discoveries are the holy grail. While the contemporary art dealer’s role is to identify the next big thing, the Old Master specialist’s quest is to find the lost or forgotten big thing, before anyone else does.

Here are a few on view this week.

William Nicholson, The Yellow Jersey (1913)

Daniel Katz, 6 Hill Street, Mayfair

Depicting a charismatic young woman, faintly amused by her ostentatious ostrich feather that appears pulled from a dressing up box, this painting by the British artist William Nicholson was missing for 80 years until it resurfaced in Scotland a year ago. Then, the identity of the sitter was unknown, but her granddaughter saw an image of the painting used on London Art Week's publicity material and contacted the gallery. Tom Davies, the director of Daniel Katz, says: “A few weeks ago we picked up the phone to the granddaughter of the actual sitter who turns out to be the actress Felicity Tree, [the artist's son] Ben Nicholson’s best friend and daughter of Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, the famous theatre producer.” Here, Tree calls to mind the sitters of Frans Hals and Diego Velasquez Nicholson, as, Davies says, Nicholson “is grappling with formality and informality”.

Anthony Van Dyck, The Penitent Saint Peter (around 1616-18) Colnaghi

Anthony Van Dyck, The Penitent Saint Peter (around 1616-18)

Colnaghi, 26 Bury Street, St James's

This large oil on canvas was attributed to Peter Paul Rubens when it was exhibited at the Palacio de Velazquez (Parque del Retiro), Madrid, in 1977. But, after a clean, it has been revealed to be an early work by Van Dyck, dating from the formative period when he was working in Rubens' studio as a young man of around 19 or 20. The work has been owned by the same aristocratic Spanish family since the 18th century—it was certainly in the possession of the 5th Marqués de Moscoso, by January 1774, as it is mentioned in the Papal Indulgence granted to him by the Archbishop of Seville. But the family has now decided to sell it, so, newly installed in a grand frame, this week it hangs in St James’s with a seven-figure price tag.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Portrait of a Man (Antoine de Ville, 1630-1635) Robilant+Voena

Artemisia Gentileschi, Portrait of a Man (Antoine de Ville, 1630-1635)

Robilant+Voena, 8 Dover Street, Mayfair

This is the ultimate feminist swagger portrait. Born in Rome in 1593, Artemisia Gentileschi (daughter of the painter Orazio) was no shrinking violet despite being a woman in a man’s world. Well connected, she mixed with other artists in Rome and was a prolific painter of both Old Testament heroines and big, bold portraits, though few are known today. During Robilant+Voena’s exhibition in 2011, Judith Mann, the European art curator at the Saint Louis Art Museum in Missouri, attributed this depiction of the military engineer Antoine de Ville, from an American private collection, to Gentileschi. Always inventive with her placement of signatures, here the artist incorporated her initials in the silver trinkets worn around de Ville’s neck. The work is priced in the region of €3m.

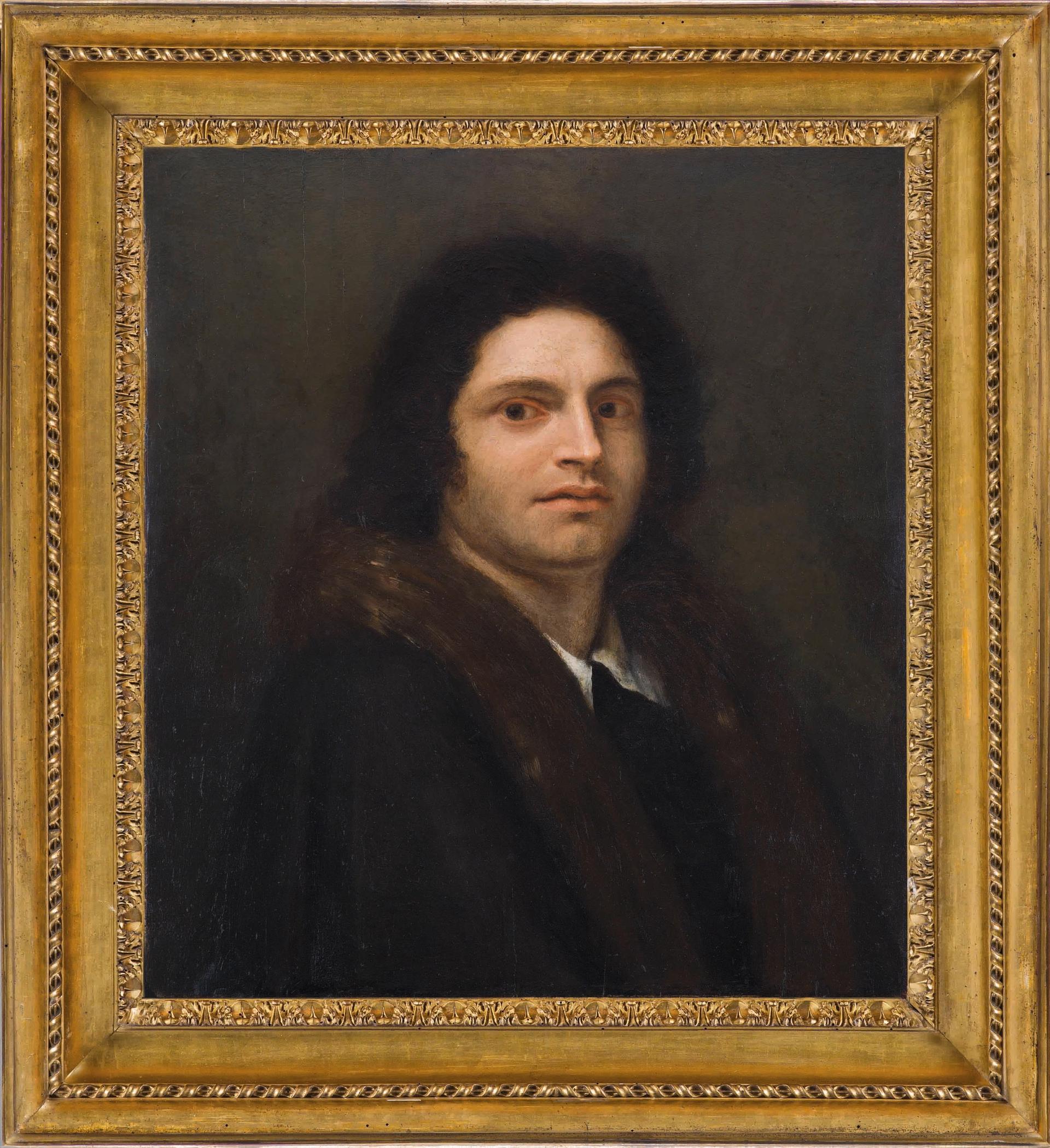

Antonio Canova, Self-portrait of Giorgione (1792) Antonacci Lapiccirella

Antonio Canova, Self-portrait of Giorgione (1792)

Antonacci Lapiccirella, exhibiting at M&L Fine Art, 15 Old Bond Street, Mayfair

This painting is an 18th century prank; a supposed self-portrait by the 16th-century Venetian painter Giorgione, but painted by the sculptor Antonio Canova to fool fellow artists at a lunch in Rome in 1792—and they believed it. It was rediscovered in a Roman collection by the Rome-based dealers Francesca Antonacci and Damiano Lapiccirella. “We were shown this painting and realised pretty quickly that, although it was painted on what looked like a typical 16th-century wood panel, the painting looked late 18th century,” Antonacci says. They had it X-rayed and found an older depiction of the Holy family underneath. “We knew the story of the Canova painting—a self-portrait of Giorgione—and D’Este's biography of Canova mentions that he bought a panel with exactly such a subject for his attempt to fool his fellow artists.” The attribution was then confirmed by the Canova expert Fernando Mazzocca. Not seen in public for more than 200 years, this is thought to be the last Canova painting on the market and “we are hoping it will be bought by a museum or institution so it can be on public view in the future, hence we have priced it conservatively [at just under £1m],” , Antonacci says.