Travelling through Wales in a bumpy minibus, feeling vaguely travel sick, I did begin to wonder what on earth I had let myself in for. We’d already been travelling for hours, and the tiny Narberth Museum in Pembrokeshire in the far south-west of the principality was still some way away.

It was 2013 and I was one of the judges for Art Fund’s Museum of the Year award, alongside the excellent and always entertaining team of the artist Bob and Roberta Smith, the historian and broadcaster Bettany Hughes, Tristram Hunt, then a Labour MP, and Art Fund director Stephen Deuchar. In those days, you shortlisted ten museums, and we had been so keen to reflect the regional spread and huge variety of the institutions originally considered that we had drawn up a travel plan that took us the length and breadth of Britain.

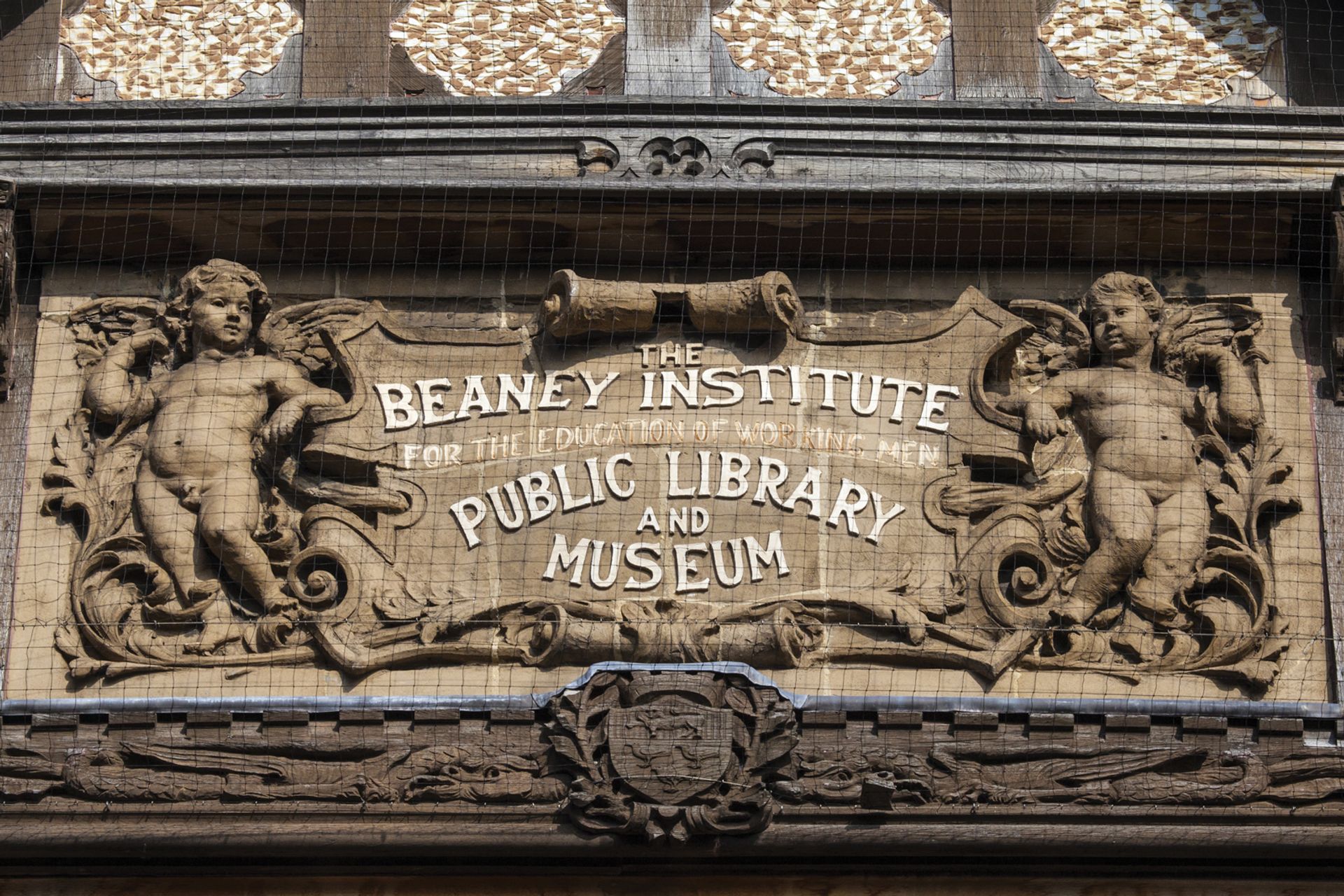

The prize, ironically, went to the William Morris Gallery, right on our doorsteps in London. But the judging process took us to Kelvingrove in Glasgow, the Preston Park Museum in Stockton-on-Tees, the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, the Hepworth Wakefield, the Baltic in Gateshead and the Beaney House of Art and Knowledge in Canterbury, plus the Dulwich Picture Gallery and the Horniman Museum, both in south London.

The Narberth Museum Tom Plumb

The vagaries of the national train timetables became more familiar to us than our own family’s faces, but the richness and pleasure of that time stays with me still. It was a pure joy to experience those buildings, to meet the people who loved and cared for them, to be encompassed by their enthusiasm and their knowledge.

Narberth, when we finally reached it, was a perfect example. Housed in a former warehouse built to house wines and spirits, which was itself saved from dereliction by the project, it is a welcoming place driven by the concern for local history of its small staff and a team of volunteers. Its collection isn’t grand, or particularly unusual, but it is full of the everyday objects of the past, which, taken together, build a vivid picture of a time and a place. Most thrillingly, it has a working model railway that replicates the original timetable of the transformative arrival of steam in Narberth in 1866. I could have stayed all day, watching the past running like clockwork.

“Anything becomes interesting if you look at it long enough,” wrote Gustave Flaubert. It’s a phrase that should be the motto of all the small and medium-sized museums that pepper Britain like beacons of light. Their existence is a tribute to the human instinct for curiosity and for collecting. Not to mention a desire to hoard and hold onto history, just in case there is any danger of forgetting.

Each one is unique, which is part of their appeal and their importance to the ecosystem. But they have qualities in common. Many preserve something that others might overlook—and that might be in danger of destruction without them. Nichola Johnson, formerly director of the Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts in Norwich, now a visiting professor in curation at Norwich University of the Arts, points to the 100th Bomb Group Memorial Museum near Diss as an example. Based at the former USAF B17 base, it is not much more than a restored control tower and a field, but the information on display is so deeply mined, and presented with such profound respect, that people come from all over the world to visit.

Like many smaller museums, the 100th Bomb Group Memorial Museum is powered by the rocket fuel of devoted volunteers. You can see their influence on this year’s shortlist for the Museum of the Year, too—supporting Brooklands and Tate St Ives, informing the Glasgow Women’s Library and the Postal Museum. Volunteers want to share their enthusiasm, to celebrate the history they are displaying, and if their energy is harnessed by a sympathetic and equally knowledgeable professional staff, the effect is dynamite.

The Beaney House of Art and Knowledge Chris Dorney

It is important, too, to recognise just how valuable their work is. You only have to look at the sorry saga of London’s Women’s Library to realise that the artefacts of social history are incredibly vulnerable. The actual collection of more than 60,000 books, pamphlets and works on paper, and its objects and personal archives, survives at the LSE after a public petition to save it. But the building in which these were housed, adapted specially for the purpose from an 1846 washhouse, has reverted to general use at the London Metropolitan University, which showed scant regard for history when it came to look at its financial position. In Glasgow, by contrast, the combination of a grassroots movement and a committed professional staff has made the place the only accredited museum in the UK dedicated to women’s lives.

“Sometimes people say we have too many small museums, but I think they are immensely important to the ecology of our museum sector,” says Hunt, who went on from travelling around in the back of a minibus to become the director of the V&A. “They often innovate in nimble ways which are fully attuned and receptive to their audiences. The best ones have a confidence about their place and their meaning, which means they don’t over worry about the latest currents in museology.”

The Narberth Museum’s exterior Tom Plumb

This insight is incredibly important. Small and medium-sized museums, when they are functioning properly, talk to their visitors in different ways than national museums and galleries. Sometimes, this is quite literal.

I was struck when I visited the Ferens Art Gallery at the end of last year at how the gallery attendants engaged with people who had come to see the Turner Prize display, mounted in the gallery as part of Hull’s time as UK City of Culture. They really talked about the art, making suggestions of a kind I couldn’t imagine a gallery attendant at Tate doing; they made it matter because they were willing to discuss it.

Johnson believes this is because they have learned to listen as well as to explain. “If you listen and then react proactively to what you’re hearing from your existing and potential audience, that makes you do things differently than if you’re inspired to do what you do on the basis of what happens in other museums,” she says.

The willingness of small museums to break the rules is part of what makes them special. But they give museums a good name in other ways as well. If you’re a holidaymaker strolling down Cromer Pier and you’re tempted to pop into the nearby Henry Blogg Lifeboat Museum, you will not only discover the extraordinary story of Blogg (saviour of 873 lives), but also of the bravery shown by all those who have set out from here to rescue people at sea. If you go there as a child, then you might not think another building with the word museum attached is too daunting, and from then on an entire world might open in front of you.

It did for me. When I was growing up, I was forever wandering into small spaces stuffed with interesting things: the Hall i’ th’ Wood Museum in Bolton, where my namesake (but not my ancestor) Samuel Crompton developed his revolutionary spinning mule; the gallery of costume at Platt Hall (currently closed); the SS Great Britain in Bristol, which prompted a long obsession with the great Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Each was full of a small piece of the social and intellectual history that make up a part of the large tapestry of British life. They fed and encouraged my curiosity.

These weren’t imposing places; they didn’t offer much in the grand sweep of things. But they did make me feel that museums and galleries belonged to me as much as they did to anyone else. They gave me permission to explore. Later, when I carried on that journey in the V&A, the British Museum, the National Gallery, smaller portals for discovery always remained enticing and enjoyable as well. “Small museums are great forces for civil society,” Hunt said when I asked him why he valued them so much. So they are. One of the great values of the Art Fund Museum of the Year prize is that it recognises that and includes them as of right. Even if that does involve a certain amount of travel sickness on the part of its happy judges.

The 100th Bomb Group Memorial Museum’s control tower Tamara Bennett/100th Bomb Group Memorial Museum