Glasgow Women's Library Marc Atkins/Art Fund, 2018

Glasgow Women’s Library (GWL) is considering a name change. “We check in with this at intervals,” says Adele Patrick, the founder and lifelong learning and creative development manager of what is the UK’s only accredited museum devoted to women’s history. “Maybe the momentum that Museum of the Year has brought about will make us take the leap of faith.” A new name would need to “signal that it’s more than a library, that it’s open to all and that we don’t just work in Glasgow”, she says. It might not, however, include the word “museum”, which risks being “even more off-putting to people who have felt a barrier around culture”.

Unlike the world’s many museums built on the collections and largesse of elite patrons, GWL has grown from the grassroots. It opened in a small shop front in September 1991 as a legacy of the feminist arts group, Women in Profile, established in reaction to the overwhelmingly white and male face of Glaswegian culture in the run-up to the city’s 1990 European Capital of Culture celebrations. Records from the group’s activities, such as the landmark public art project Castlemilk Womanhouse, formed the beginnings of the GWL collection. Remarkably, this continues to be entirely crowdsourced; there has never been an acquisitions budget. Donated items range from suffragette memorabilia to lesbian pulp fiction, knitting patterns to roller derby helmets.

The library managed for almost a decade without public funding or paid staff. “It took a lot of courage to commit to the idea that we were actually in this for the long term,” Patrick remembers. Recent years have marked an “incredible watershed moment”, she says, with milestones including the move to a permanent building in Glasgow’s East End in 2013 and a £1.4m refurbishment in 2015, the year that GWL also gained full accreditation from Museums Galleries Scotland. In 2016, it celebrated its 25th anniversary with a raft of high-profile exhibitions and events.

So what makes 2017 the library’s standout prizeworthy year? Having settled into a new, more accessible home, “we really started seeing our ambitions to be a significant player in the museums sector manifest [themselves]”, Patrick says. The all-women team could shift focus from the building project to a longer-term strategy for programming and collecting. The library chose Linder Sterling for the first in a series of contemporary art commissions, presented this April as part of the Glasgow International festival. It also unveiled its first permanent exhibition of museum and archival objects, helping to double visitor numbers. True to GWL’s community-rooted approach, the curators were all local volunteers. Around 100 volunteers a year support the library, which has just one curator, one librarian and one archivist on staff—all part-time.

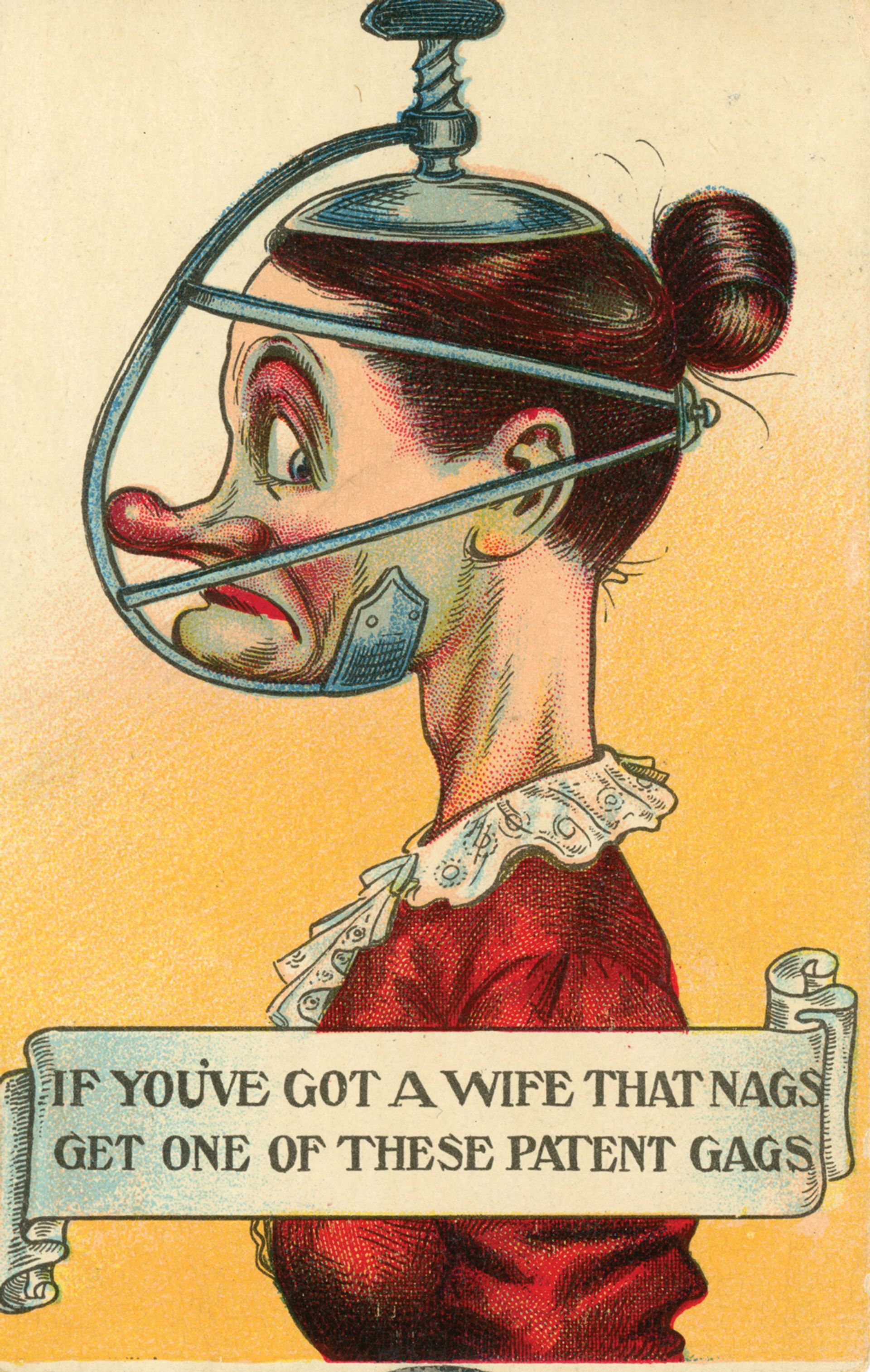

GWL’s shocking collection of anti-suffragette postcards shows how the picture postcard industry was utilised to denigrate women fighting for the vote Courtesy of Glasgow Women’s Library

Crucially, the institution has come of age at a “sea-change” moment for feminism and activism in the museums sector and society at large, Patrick says. GWL’s announcement of its Museum of the Year nomination refers directly to the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements and to “the blossoming of calls for action on representation and inclusion”. For Patrick, being shortlisted signifies “a wider recognition that change is happening and that we typify something that is now welcome in the sector”.

That “something” includes taking a stand for social justice. Besides being a repository for past political campaigning, GWL has embarked on projects tackling issues that affect women’s lives today, such as hate crime, sectarianism and sexuality. A “rapid-response” display around Ireland’s abortion rights referendum in May should be ready by August.

Behind the scenes, the library’s emphasis on equality, diversity and inclusion as guiding principles for everything from governance to collection development is inspiring other cultural organisations to review their policies. Backed by the Scottish government and the European Social Fund, GWL launched an initiative called Equality in Progress last year. So far, Patrick says, it has delivered training to 15 partners, including Museums Galleries Scotland and the Edinburgh International Book Festival. In June, the library hosted a conference for Scottish museums professionals and published a report of the research findings.

“I think we’re evidence that this work can be done at the highest level, without an enormous amount of resourcing,” Patrick says. But how would the library spend the £100,000 Museum of the Year jackpot given the chance? “Regardless of whether we win or not, we have always been wildly ambitious,” she says. On the wish list, generated by a recent consultation with library users, are a creative retreat for writers, a space for performances and a café. “There’s certainly no shortage of ideas.”

Must see: Anti-suffragette postcards

Adele Patrick

Lifelong learning and creative development manager, Glasgow Women’s Library

Adele Patrick

“We have an incredible collection of anti-suffragette postcards. A lot of them show women who are, in different imaginative ways, being tortured for asking for the vote. On the back, they often have banal messages like, ‘Having a lovely time in Margate’, normalising what are grotesque, awful images of women. We love to use these postcards in ways that show there’s a trajectory of misogyny that is still live. It’s hard to realise just how alienated this group was, doing work that gradually became a popular movement for change. It has so much resonance with what we’re seeing now with #MeToo and other campaigns. These objects don’t have a huge financial value but are massively freighted with meaning.”