Using the $100,000 he won as part of the Nasher Sculpture Center’s 2018 Nasher Prize, Theaster Gates bought himself a printer. Not your ordinary inkjet printer—not even a cutting-edge 3D printer—but a German-made, Heidelberg Windmill printing press. It has taken up residence in the Chicago-based artist’s studio as the mechanical heart of his new publishing arm, Black Madonna Press, and a similar machine has been set up at the Basler Papiermühle, the Swiss Museum for Paper, Writing and Printing, as part of Gates’s four-city series of exhibitions focusing on the theme of the Black Madonna. Based on the image of the Virgin Mary with dark skin found in many Medieval works across Europe, it launches this month at both venues of the Kunstmuseum Basel (until 21 October), along with live performances, recordings and printing workshops at other venues in the city. The series continues at Hannover’s Sprengel Museum (from 22 June 2018) and Munich’s Haus der Kunst (from October 2018). We spoke to the artist about the project.

Gates’s Heidelberg printing press has transformed his practice; it has even “overtaken my primary sculpture space” Printing Press: Photo: David Sampson; Courtesy of Theaster Gates

The Art Newspaper: Why did you decide to start the Black Madonna Press?

Theaster Gates: I learned bookbinding when I was in the craft world, making my own books and small journals, but also starting to play with restoration. So printing and book art has always been on my mind, and all of the amazing work of the concrete poets and Carl Andre and 1970s typewriter art. I just love that world as its own alternative genre of conceptual practices that were emerging in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

I had been looking for my way in, having this background with spoken word, and it was really through this exhibition in Basel, also titled Black Madonna, that I had the idea of reflecting on sacred texts and on the black woman as a theme worth disseminating. In some ways, the Black Madonna Press takes its cues from the Johnson Publishing Company, and a lot of the original content that we produce will actually be content inspired by, or images appropriated from, the Johnson Publishing collection.

Have you been using the press already?

Yes. Johnson Publishing was kind enough to license the use of several thousand images from its collection for my exhibition. I’m going to use the Johnson images as a base subject and then add my imprint on top.

I just think that much of my work—like with the Black Monks of Mississippi—is super-male, which I’m fine with. It’s been great, because it’s really been a sincere effort to talk through my experience. But on the occasion of Basel, and maybe because I’m managing my own redemption song, it feels like a great moment to publicly reflect on the power that black women have offered in my life. There’s no better Madonna than my mother.

So there are all these homages that are paid to the idea of the power of women—in this case, to survive traumatic acts against their sons [and husbands]. People like Coretta Scott King or Emmett Till’s mum or Tamir Rice’s mother, Samaria—there’s that kind of metaphoric subject of the woman who endures the unnecessary sacrifice of her children, but also just the power and how that is made even more powerful through reproduction.

The four shows that I have this summer and autumn all fall under the broad rubric of the Black Madonna because I really wanted to play out this idea of dissemination across Europe, in the same way that the icon of the Black Madonna spread through Catholicism. And then put the Black Madonna where Hitler had been. And with these texts that I’m making through the press, I’ll be able to offer these institutions a kind of New Jack prayer; to ask for forgiveness and grace, and maybe some good new energy.

The printing press had a large role in the development of religious thought and became a powerful tool in the Reformation across the continent.

Part of the reason that this thing is so absolutely relevant in Basel is because the city has this amazing paper-milling history. The paper mills, the printing presses and really important writers resided around Basel. It was one of the printing cores.

People have such narrow ways of understanding site-specificity. It isn’t necessarily about trying to glean hyper-tangible artefacts. There’s nothing that I have to say about being Swiss, you know what I mean? But there are other ways of thinking about something that’s site-specific; in this case, it was the history of the milling industry and the printing industry, combining that with the idea of Johnson Publishing. I just thought: what if John Johnson worked in partnership with 1950s Swiss designers? How could the image of the black woman or the idea of blackness with this strong, iconic commitment to printmaking and letterpress—what might those things feel like together? So I’m exploring that: Johnson meets Swiss design.

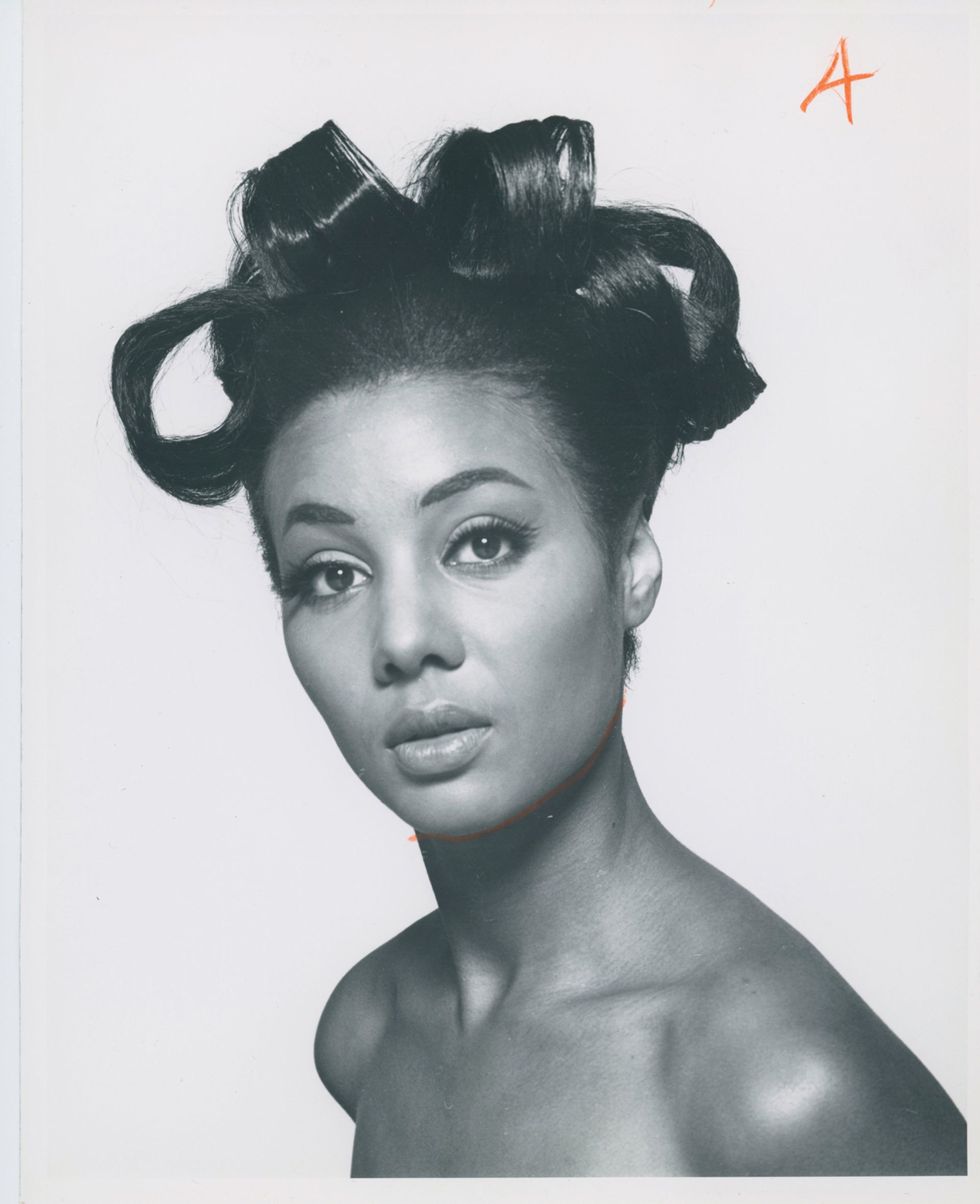

A photograph from the archives of the Johnson Publishing Company. Gates is exploring the image of the black woman in connection with printmaking: “Johnson meets Swiss design” Courtesy of Theaster Gates

When you first started preserving archives such as Johnson’s, did you ever think that process would result in this new material as well?

You know, I didn’t. But what I’ve come to realise is that I’m not a conventional archivist. I would not be very good at it; I respect the field too much. But the idea of the archive has a lot to do with helping people see [a part of] themselves they may have forgotten; and the material artefact, in this case, helps to reignite more knowledge about something. So as an artist working with archival information, my job is to help it become relevant again for a viewer; maybe so much so that they would then want to know more about the contents of the archive as a result of this indexical act that I’ve created.

I hope that visitors who see these images are like: “Damn, those are so beautiful. I want to do that” or “I want to know more about that”. Because if you’re just talking about historical facts, OK, you can become informed. If you’re talking about tragedy, OK, you can be saddened. But the way I use history, I want people to become hungry to know more of it. I want to basically feed new historians, new interrogators.

It’s also one thing to make a book and have someone else produce it. It’s another thing to be able to produce your own book and to be able to control the content; and then, as a byproduct of that, produce other people’s books, other people’s album covers or other people’s posters.

Part of what I’m excited about is having these presses so that I have this vocabulary, and that is already impacting on parts of my sculptural process.

In which ways?

Like the idea of surface. As I’ve started to print, it’s making me rethink the surface of my sculptural objects and what information goes on an object. If I’m dealing with the question of Africa in Modernism and I’m making my own African mask, all of a sudden, I’m more interested in the information that I’m able to apply to the mask that would come via the printing press. Could I put more information on the surfaces of my things to add new layers to the archive of Modernism?

And where is the printer now?

In my studio in a former brewery [in Chicago]. I moved all of my things out and put them in storage, and now the printing press has overtaken my primary sculpture space—I also think that’s saying something, in a way. I don’t have room to make any more; I have room to print.

• Theaster Gates: Black Madonna, Kunstmuseum Basel, until 21 October