Etel Adnan, who was born in Beirut in 1925, was, until a few years ago, primarily known for her writing; her 1977 novel Sitt Marie Rose won the France-Pays Arabes award, while her poetry collections include Moonshots (1966) and Seasons (2008). However, her contribution to Documenta 13 in Kassel in 2012 made her an art-world star, bringing her small, abstract canvases to new, appreciative audiences. Adnan creates works in a small studio in her Paris apartment, using a palette knife to apply paint on the canvas. On the eve of a major exhibition at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern (15 June-7 October), we visited Adnan to discuss her passion for Klee and why the Swiss artist, who has been dubbed the father of Abstract art, is pivotal to her practice. At Art Basel, Sfeir-Semler gallery is showing several works by Adnan, including a wool tapestry, Reves étoilés (1967-70/2018).

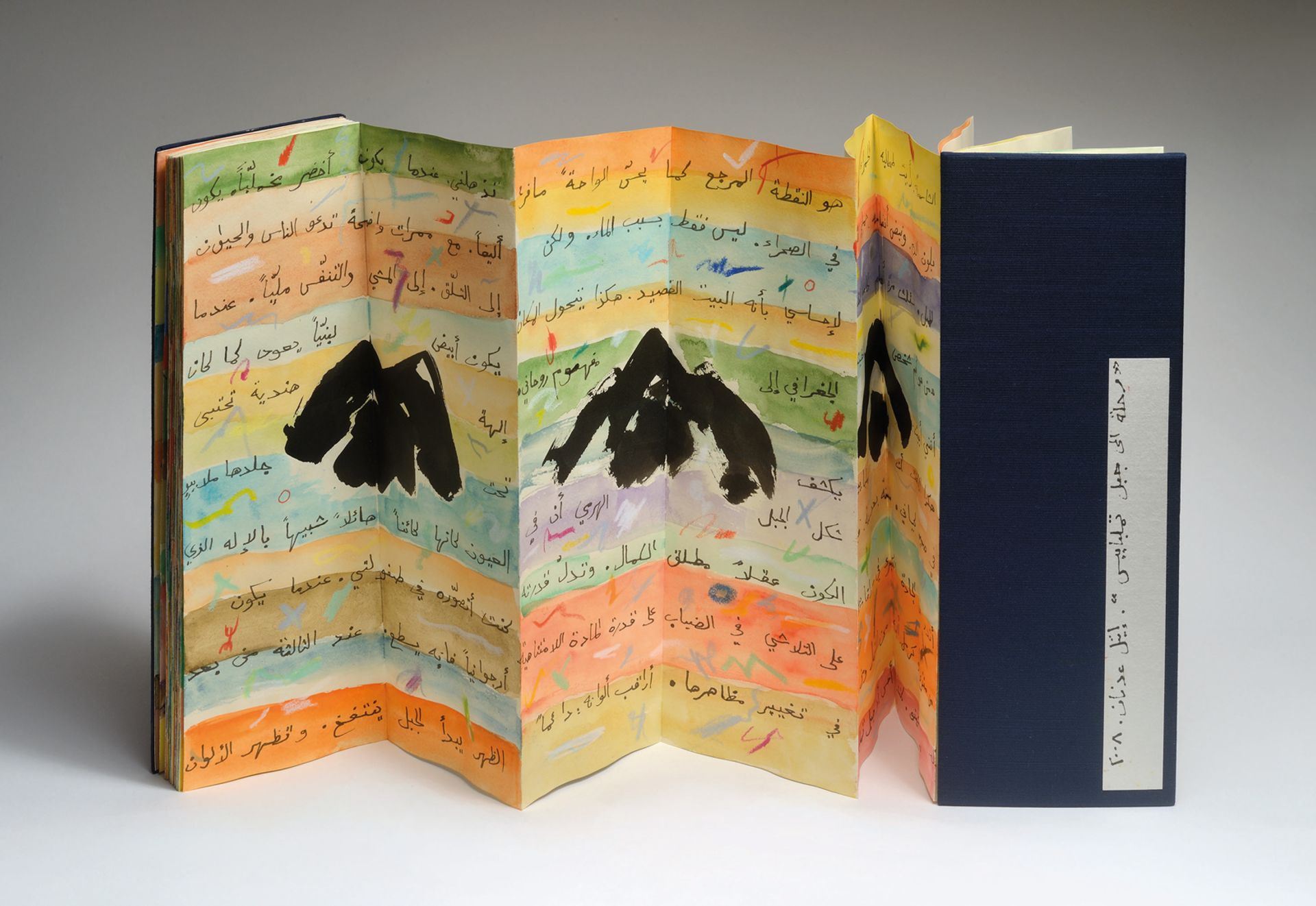

Rihla ila Jabal Tamalpais (Journey to Mount Tamalpais) (2008, above) is an example of Etel Adnan’s leporellos Etel Adnan; courtesy of Galerie Claude Lemand, Paris, and Jean-Louis Losi, Paris

The Art Newspaper: Have you always looked to artists for guidance?

Etel Adnan: I taught philosophy in California [at the Dominican University of San Rafael from 1952 to 1978] before I became a painter, and I used the writings by painters. I found out pretty soon that teaching Hegel and all these theoretical ideas was useless, and in a way, I was lucky because this is how I read the writings by painters. I discovered that painters are often great writers because they are not self-conscious.

What stands out for you with Klee’s art?

I am almost disturbed by the tragic figures that Klee creates. But he did not do too many. Some people like his marionettes, as do I because they are striking, but they are also frightful. He made them for his child [the artist made more than 50 hand puppets for his son Felix] and if I were a child, I’d be scared to death. But they are impressive. I like his gardens, that series of intimate houses, cities and gardens. And then there are two or three [key] Paul Klee periods. I like the North African period above all because I went to North Africa [Klee spent several months in Tunis in 1914]. There are usually watercolours [from this period]; maybe he made them in his hotel. He catches the light. [Eugène] Delacroix did the same; he stayed in the same places. Delacroix did it in Morocco [in 1832], Klee in Tunisia.

You’re also linked through calligraphy; you refer to Arab calligraphy in your leporellos—accordion-like pieces combining poetry and art—and Klee was interested in the structures of Chinese calligraphy.

Calligraphy is less inviting because it is really very codified, but there is calligraphy in the sense that it is the gesture of writing that counts. I like that very much, because as a child I loved the act of writing. We think that writing is intellectual, but it is also a physical activity. Your hand gets into a trance.

So this ties in perhaps with Klee’s theory that a drawing is a line going for a walk?

Absolutely. As a writer I get into a rhythm, and that rhythm is a combination of a mental and physical state. It is a total experience and Klee does that, he expresses that. And it touches me as a writer.

Do you think you both enjoy the materiality of the creative process?

We both did small canvases. He did not do huge paintings and they are very dense. You never think that Klee does small [pieces], but the works are small. We have that in common. I have worked in small formats. I always work at home and I heard that Klee sometimes worked on a kitchen table. Maybe he couldn’t afford a big studio and worked in a corner of the Bauhaus.

The exhibition at the Zentrum Paul Klee includes a wide range of your works, from 1970s leporellos to 50-year-old tapestries. How is it installed?

It is very simple. I wrote some pieces on Klee in some of my books. I asked that they be put on the walls as statements. [The curators] also asked me to write a piece on his angels [the text Angels, More Angels is included in the catalogue]. I wrote a paragraph on the angels in one of my short stories [Master of the Eclipse, 2009].

Untitled (2010), one of Adnan’s clearly demarcated colour compositions Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg/Beirut

What is your take on Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920)?

[The philosopher] Walter Benjamin singled out Klee’s angel, and he made it an angel of history. For me, it’s more than that. It is leonine, he has wings. He has the feet of a cow. It reminded me of the symbols of the Four Evangelists [which are frequently represented as creatures]. And I found out that the young Klee was religious in his own way, so it’s not impossible. But I mean that there are many references to God. That’s another thing I like about his work; there is a spiritual search. There is a spiritual quality that goes beyond the image. Even in a landscape there is something mystical. But his mysticism sometimes becomes depressing for me, and I think he was close to depression.

How do you feel about garnering accolades for your art much later in life?

To be honest, I did not expect recognition. I was happy to keep going. Some people I respected liked my work. I was selling two or three paintings a year at very low prices, but it kept my image going. That is important. In the beginning, every article started with [mentioning] my age. I thought it was funny but I got a little annoyed. I won’t make an issue out of that; most female artists who are well known became known later in life.

And were your early years steeped in art?

There was no art museum in Beirut, there were no paintings at home. We had rugs, and the aesthetic pleasure came out of those. When I was 20, I started university. There was a young Armenian student who did little paintings of olive trees, and they were beautiful. The director of the French department gave him a show in the library. We now had a colleague who was a painter. And when I came to France as a scholarship student aged 24, I discovered the Louvre. It was empty at that time and I would wander by myself. There were two or three things that struck me, including the Venus de Milo and the Winged Victory of Samothrace.

You started painting at 34; has your practice changed much?

I didn’t change my practice. You know, all artists change but something of them remains through art—their identity. You recognise a young Cézanne and an old Cézanne, although you see the difference. I still enjoy painting very much. In fact, when I am tired or worn out, then I’ll go and paint.

And the Klee exhibition is hugely important?

I really do believe that it is the summit of my career.

Hans Ulrich Obrist Art Basel

Pulling power of two greats

Hans Ulrich Obrist, the artistic director of London’s Serpentine Galleries, on what connects Paul Klee and Etel Adnan

Etel Adnan is one of the world’s great poets and artists. The energy and magnetism of her work attracted me from my very first encounter with it—in one of her leporello notebooks—and I immediately wanted to know more. I experienced something very similar on first seeing the work of Paul Klee as a teenager in Switzerland. Adnan once said to me that Klee belongs to the lineage of geniuses for whom a single designation—whether “painter”, “musician” or “architect”—is too narrow. Every painting by Klee is like an act of discovery, achieved through a process of exploration.

“Like a boat on the ocean,” according to Adnan, “he was not directing the painting, the painting was telling him… He had the courage to go into the unconscious and to see the terrifying side of human beings. He painted the most paradise-like of gardens and the most strange and total insanity in human beings. He goes in all directions that a mind can go.” We must pay attention to Klee’s writing, she said, as we must to the poetry and prose of such polymaths as Leonardo da Vinci, Wassily Kandinsky and Igor Stravinsky.

• This is an excerpt from a text for the Weight of the World exhibition at the Serpentine Galleries in 2016