As Palestinians die protesting for the right to reclaim property and other freedoms they lost when Israel was founded 70 years ago, an Israeli art historian is giving them access to the photographs, films and other materials that have been taken from them over the decades. For the first time, Palestinians can see images of their lives buried in Israel’s military archives from before and after they fled or were exiled during the 1948 war that led to the establishment of Israel.

Property and heritage disputes and other issues were meant to be addressed by peace negotiations between Israel and Palestinians. But as talks stalled, the contentious issues have gone unresolved. Now, Rona Sela, a curator and lecturer at Tel Aviv University, has achieved one small part of what the politicians and diplomats have failed to deliver.

After spending 20 years uncovering Palestinian materials in Israeli archives, last month she published the first translation of her findings in Arabic. Her book includes photographs taken by Palestinians of their lives, surveillance materials of Palestinian villages assembled by Jewish soldiers, and images showing the destruction of Palestinian villages, and life under Israeli rule.

The work is an updated version of a 2009 Hebrew-language publication and includes materials Sela has uncovered since then. Translated by the author Ala Hlehel, it is published by Madar, a Palestinian research centre in the West Bank.

“We can’t access this material directly,” says Honaida Ghanim, a Palestinian sociologist who is the director of Madar. “But at least we have been given another window to our past, to get a fuller picture of what happened and what was destroyed.”

Confiscated property

After Israel was established, it confiscated property left behind by the 750,000 Palestinians who fled or were exiled. A 1950 Israeli law classified Palestinian homes and other buildings and their contents as Israeli property. Photographs, films, documents and other cultural assets such as libraries disappeared into Israeli archives, Sela says. “Soldiers continued to seize and loot other Palestinian photographs, films and documents during the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and other military raids and intelligence gathering missions.”

Most of these confiscated materials remain inaccessible in Israeli military archives, as Israel can classify documents for up to 70 years, or indefinitely, if they are deemed to be related to security or international relations.

Nevertheless, Sela has made important discoveries, most recently a photography collection confiscated during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon from the Cultural Arts Section of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation in Beirut.

A photograph of a marching band (date and photographer unknown) from the Israel Defence Forces Archive unknown

Alongside her search in the archives, Sela tracked down Palestinian photographs and films elsewhere. She interviewed Palestinian photographers, film-makers, artists, archivists and their families about what had happened to their possessions. She also interviewed former Israeli soldiers about the confiscations.

She says she was often deeply moved by the materials she discovered, imagining the Palestinian families who were longing to see them. The daughter of Holocaust survivors, Sela herself grew up without photographs of her grandparents or their lives in Poland and Belgium, and strongly believes that the Palestinian materials in Israeli archives should be returned to the people or organisations they were taken from.

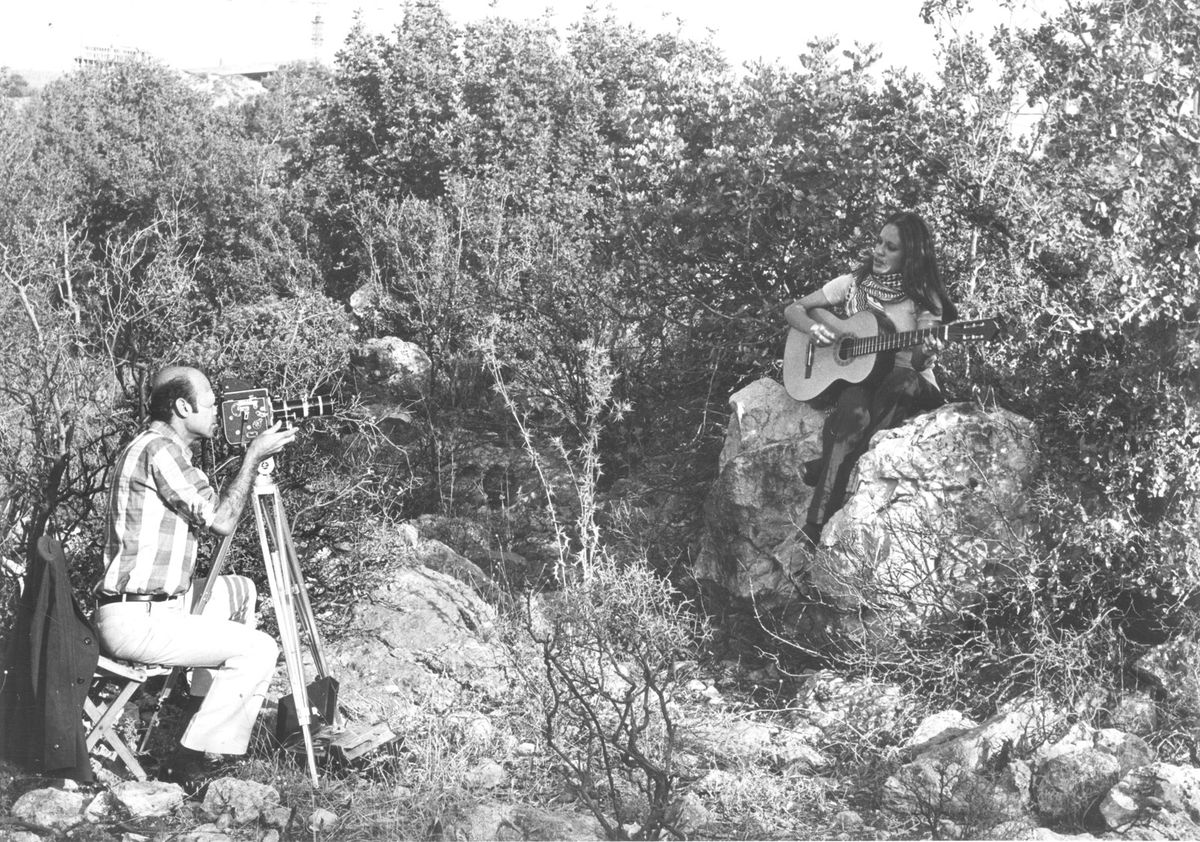

Although she was unable to retrieve original material from the archives she visited, Sela photographed, documented and researched her discoveries. Then she tracked down the families the materials had been taken from to obtain copy-right to reproduce the images. Since 2000, she has published her findings in Hebrew and English catalogues, magazines and books. Last year, she released a documentary, Looted and Hidden, about Palestinian films seized by the Israeli military in Beirut. The story is told through meetings and letters she exchanged with the Israeli soldiers who confiscated materials and the Palestinians who ran the archives they were taken from.

Returning Palestinian property?

If Israeli-Palestinian peace talks resume, “bilateral negotiations could [cover] confiscated materials and anything claimed as significant cultural heritage in a legal framework and agreement”, says Lynn Dodd, a Middle East expert at the University of Southern California. Israel could also choose to return Palestinian property voluntarily, she adds, as states and institutions have started to do in other situations. “Voluntary repatriation of objects could be initiated by an owner,” Dodd says, “or by Israel, if public debate forces its hands, or [to] serve emerging norms of justice.”

For now, the material remains in Israeli hands. But Palestinians and even many Israelis think at least the material should be fully accessible.

Yaacov Lozowick, Israel’s senior archivist under the Prime Minister’s office, who has called the archive policies “undemocratic”, believes “everything in the archives should be declassified and put online”, adding that there are plans to translate the search engines currently available only in Hebrew into Arabic.

• Rona Sela’s book, Made Public (in Arabic), is available at madarcenter.org