For much of his long artistic career before he died aged 84 in March last year, Howard Hodgkin was renowned as a slow painter. The tale of his rich, colourful pictures’ long journeys to completion was told in the parenthesised dates alongside his evocative titles: Sad Flowers (1979-85), Love Letter (1984-88); Snapshot (1984-93). But in recent years, as is clear in the tremendous exhibition of 32 works from the past decade at the Gagosian Gallery in Grosvenor Hill, London, the period between Hodgkin’s first mark and his final gesture was often much shorter. And just before he died, he had an extraordinary burst of activity, completing six paintings in five weeks on a final trip to his beloved India in December 2016 and January 2017. All six are in the Gagosian show; five of them are being shown for the first time.

Antony Peattie, the music writer who was Hodgkin’s partner in the final four decades of his life, says that Hodgkin “had got into the habit of spending winter in India, mostly in Mumbai/Bombay”. They took an apartment there, converting a second bedroom into a studio. “There was something about India and the circumstance that allowed Howard to work,” Peattie says. “Partly it was that the difficulty of being there meant that there wasn’t much else that you could do.” Hodgkin used a wheelchair towards the end of his life, a tricky proposition amid the traffic, bustling streets and banyan trees in Mumbai, “so we scarcely ever went out except by taxi. So Howard was in the apartment looking at the view, and that included the Indian Ocean on one side and Gothic Bombay on the other, and if you woke very early there was dawn. And somehow there was the sunset, too. So the apartment and the life there suited work. And that became his absolute priority; he just wanted to work.”

Hodgkin had not made any paintings the previous autumn after completing Portrait of the Artist Listening to Music [2011-16] for his exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London last year, which turned out to be posthumous. “He didn’t do anything else in the studio that autumn,” Peattie recalls, “he kept it all in his head, because when we got to Bombay and they fitted up the studio, he finished six paintings in five weeks, which was completely unheard of, it was a completely different work-rate and completion rate. It was astonishing, they just poured out of him.”

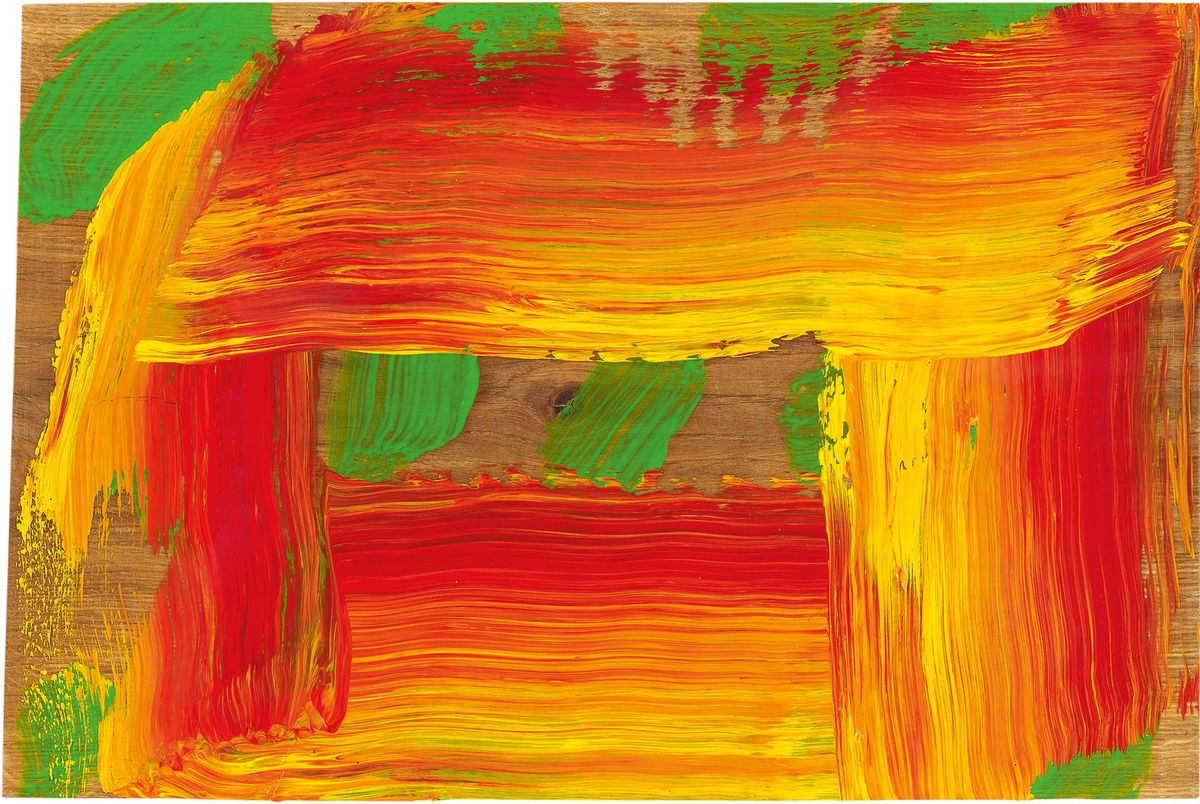

The six final paintings—A Green Thought in a Green Shade (2016), Red Sky in the Morning (2016), Over to You (2015-17), Indoor Games (2016-17), Cocktails for Two (2016-17) and Indian Sea (2016-17)—are remarkably vivid and dynamic. “It’s like a flame because they’re all different, too,” Peattie says. “There are artists who do series and it has a very respectable history—whether it’s electric chairs or haystacks, good artists have done series. But Howard didn’t: each picture is a fresh journey out from a different proposition, so they’re incredibly disparate, and each one is so fully realised, it’s shocking. I think he must have been aware that this was it. Because he didn’t give up: he tried to paint when his body failed him in India, but he couldn’t—his hands trembled and he couldn’t stand, even to paint. Because he sat a lot towards the end; he said: ‘I think more and I paint less.’”

Where once Hodgkin’s paintings bore the years of additions and revisions on their surfaces, his late work was much sparer, and this is especially true of these last works, where “the paint is often thin, thinly layered, or leaving expanses of wood to be eloquent in their own right”, as Peattie says. The titles often quote literally sources—A Green Thought in a Green Shade is a line from Andrew Marvell’s 17th-century poem The Garden; Indoor Games is Betjeman poem; and Over to You is a line from Stevie Smith’s Mr Over. But, Peattie says, “some of his titles do not point you in the direction of their source”. Over to You “alludes to a Stevie Smith poem but it’s not an illustration to the poem and you couldn’t print the picture next to the poem and expect people to say: ‘Oh yes, there he is: He died, fighting and true/And on his tombstone they wrote/Over to you.’ No, I think he takes the phrase and makes it his own. And Over to You suggests to me the artist presenting the work to the public and saying: ‘There.’”

• For the full interview with Antony Peattie listen to The Art Newspaper Podcast, episode 33