It is a salve to see an exhibition as succinct, as purposeful, intelligently designed and filled with good art as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new show History Refused to Die (until 23 September). It highlights a generous, recent gift of 57 works from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and powerfully affirms the vibrancy of America’s visual culture beyond the coasts and big cities.

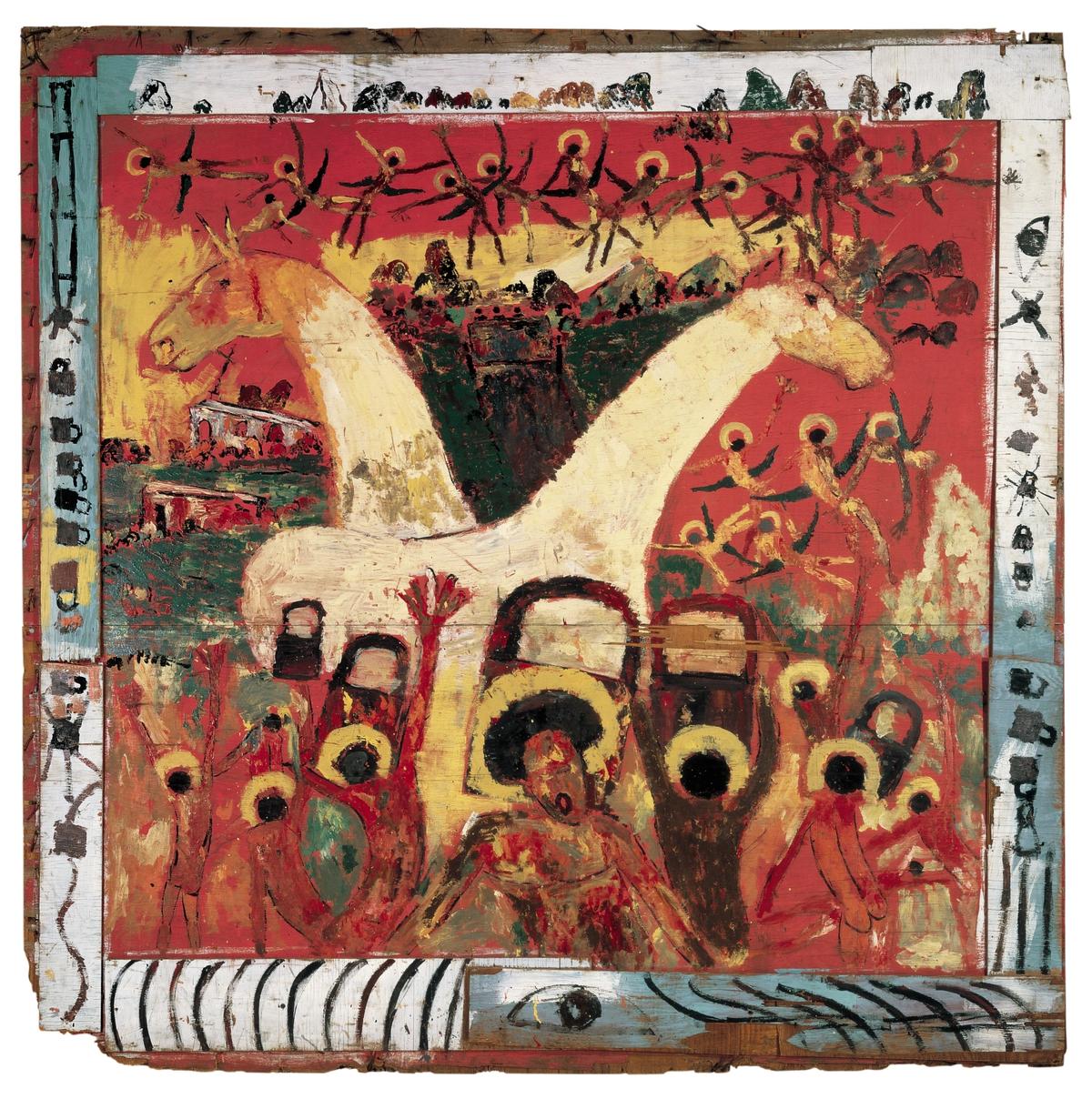

The objects go from strength to strength. The gifted Thornton Dial is the biggest star and his two-sided multi-media construction, History Refused to Die (2004), is gorgeous. It is polemical and overwrought, done toward the end of Dial’s long career and a new take on the long tradition of history painting—if we can call it that since it’s much more than paint. It is dense, jagged, puzzling, lush, inscrutable, and, like the past itself, open to different interpretations. Dial is an abstract artist given to patterns and unorthodox, found materials. He is also a realist, faithful to the look and feel of a world close to the land, where people are scrappy, poor and stubborn. It is as grand as an altarpiece.

Thornton Dial, History Refused to Die (2004), okra stalks and roots, clothing, collaged drawings, tin, wire, steel, Masonite, steel chain, enamel, spray paint 2018 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

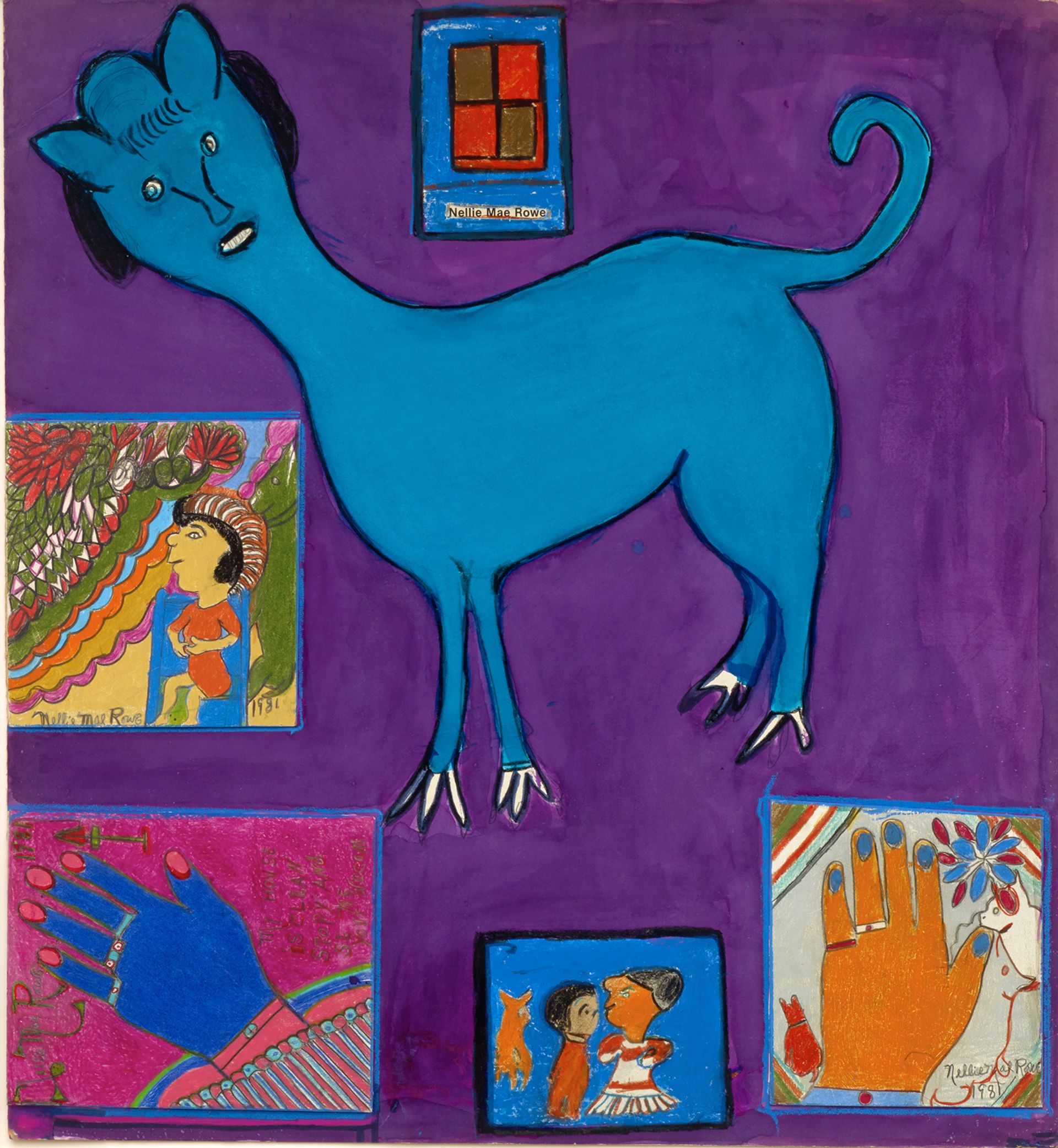

A big gallery also shows Dial’s large, abstract drawings, one of chaotic swirls entitled, Interrupting the Morning News (2002), a memorial to the 11 September attacks, flanked by a set of brightly coloured, abstracted figure drawings by Nellie Mae Rowe on one side and a wild, totemic mask made of junk by Lonnie Holley nearby. I did not realise until I looked at the label that the notorious series of child murders in Atlanta in the 1970s inspired one of Rowe’s figure drawings. It is an unsettling work, as if a child tried to convey something scary he could neither understand nor explain with words. The blue skinned beast that stands in the middle has both a childish simplicity and a medieval menace, with sharp teeth and hooves.

Nellie Mae Rowe, Atlanta's Missing Children (1981) 2018 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

On the other side of the gallery is a selection of Gee's Bend quilts showing different palettes and patterns. The best quilts are the monochromatic ones, often with shades of blue from found fabric, mostly faded denim cut in geometric shapes and irregularly stacked. It is tonalism but the aesthetic is different from what an artist would get from paint. The quilts with lots of red, white, and black are jazzy and buoyant but these have a cool, serene elegance. Every quilt has contrasting textures among pieces of fabric, some more subtle than others and this unpredictablility is integral to their beauty.

Together, these objects show the range and depth of the Met’s gift. They also say plenty about the curators’ skill in putting them together. They play well, however disparate they are, because the artists broadly share the same roots and experiences.

Annie Mae Young, work-clothes quilt with center medallion of strips (1976)

The show's catalogue is also great. In three sensible essays, the scholars pry the work from the heavy baggage some of it has carried, especially the quilts. I thought the big 2002 Gee’s Bend traveling show introducing these objects both overplayed their merit and saddled them with the unrelated vocabulary of post-war painting. Linking them to Kenneth Nolan, Stuart Davis, or Joseph Albers is understandable. We puzzle out things we do not know by finding similarities with things we do. These quilts come from a different world. As an alternative, critics sometimes tried to tie them to carried down African traditions, consciously observed by the makers or deployed by unwitting habit. That is subtle colonialism and unfair. The artists are from families here for hundreds of years.

The curators and I agree that calling them “craft” as opposed to “fine art” is also meaningless. The makers intend to give visual pleasure. They show great skill in judging nuance in colour and material. That the objects are used to keep people warm adds to their sensual allure. American art is unusually practical, so we can leave at the door thoughts of boundaries and classifications, among them the walls that separate self-trained from credentialed artists. This lovely show and its fine scholarship add new strands to our understanding of what makes American art uniquely American.